[Early Printing in English] [Rhetoric - Vernacular - English] [Shakespeare’s influences]

$3,900

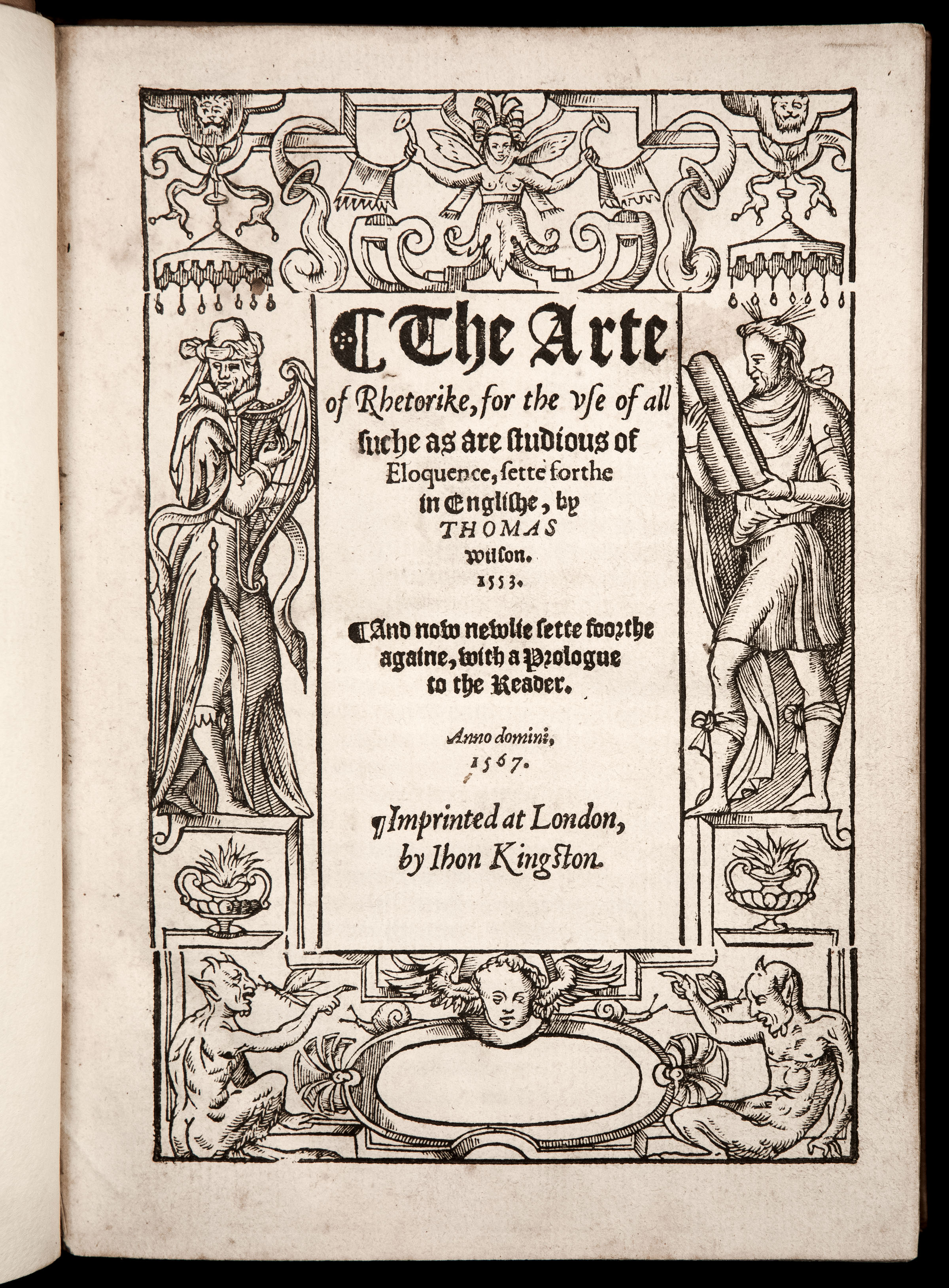

London: John Kingston, 1567.

Text in English (with some words in Latin).

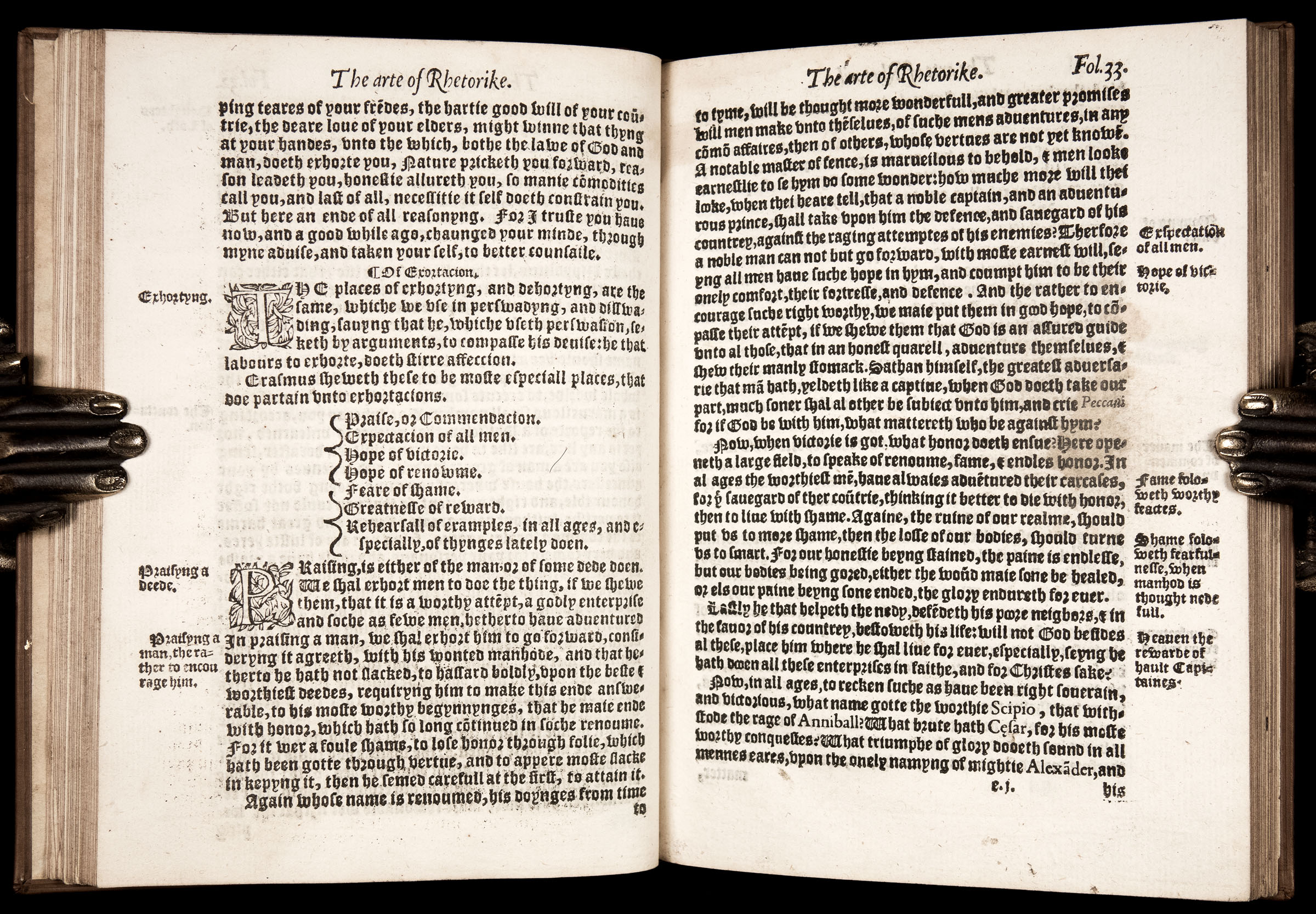

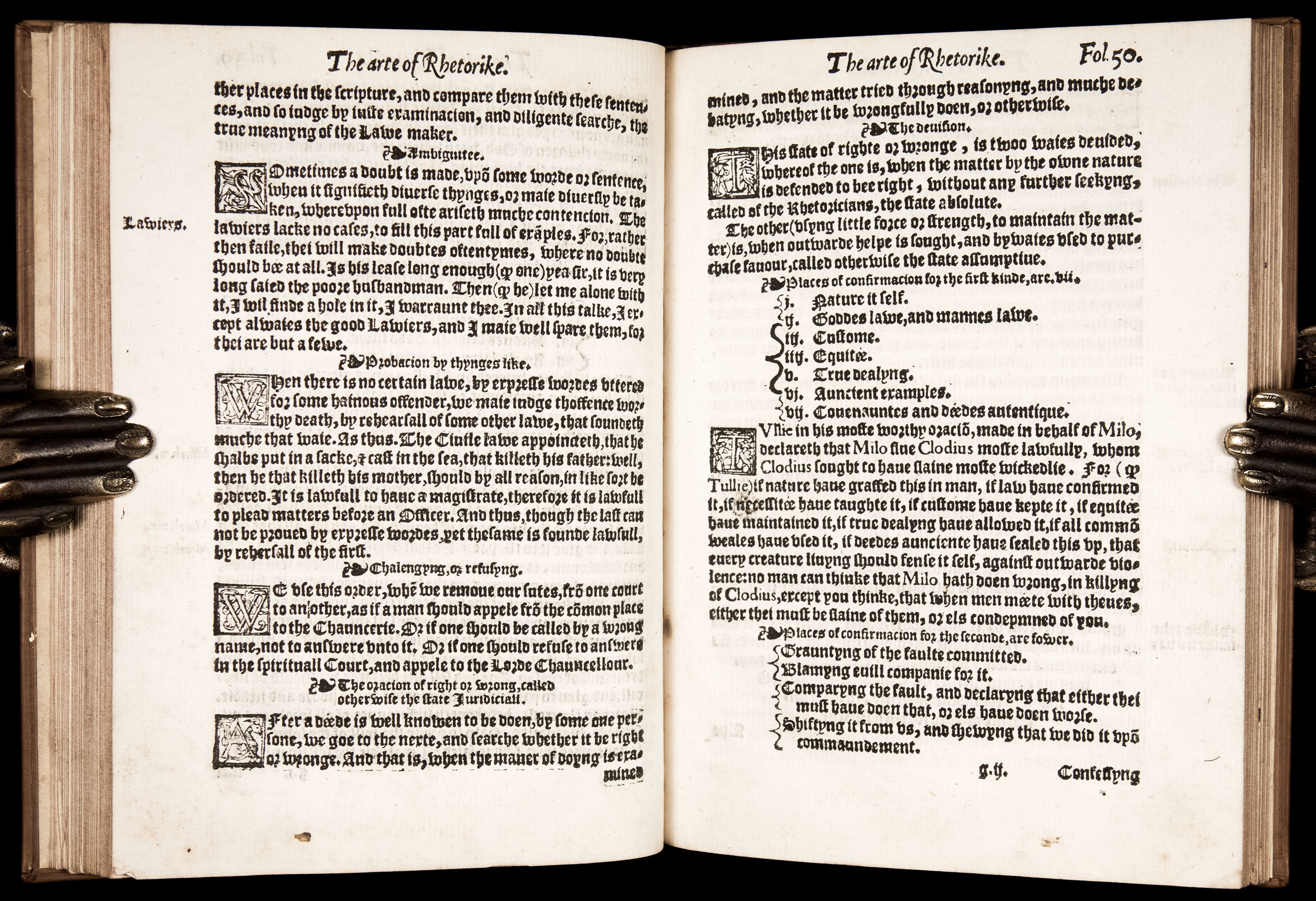

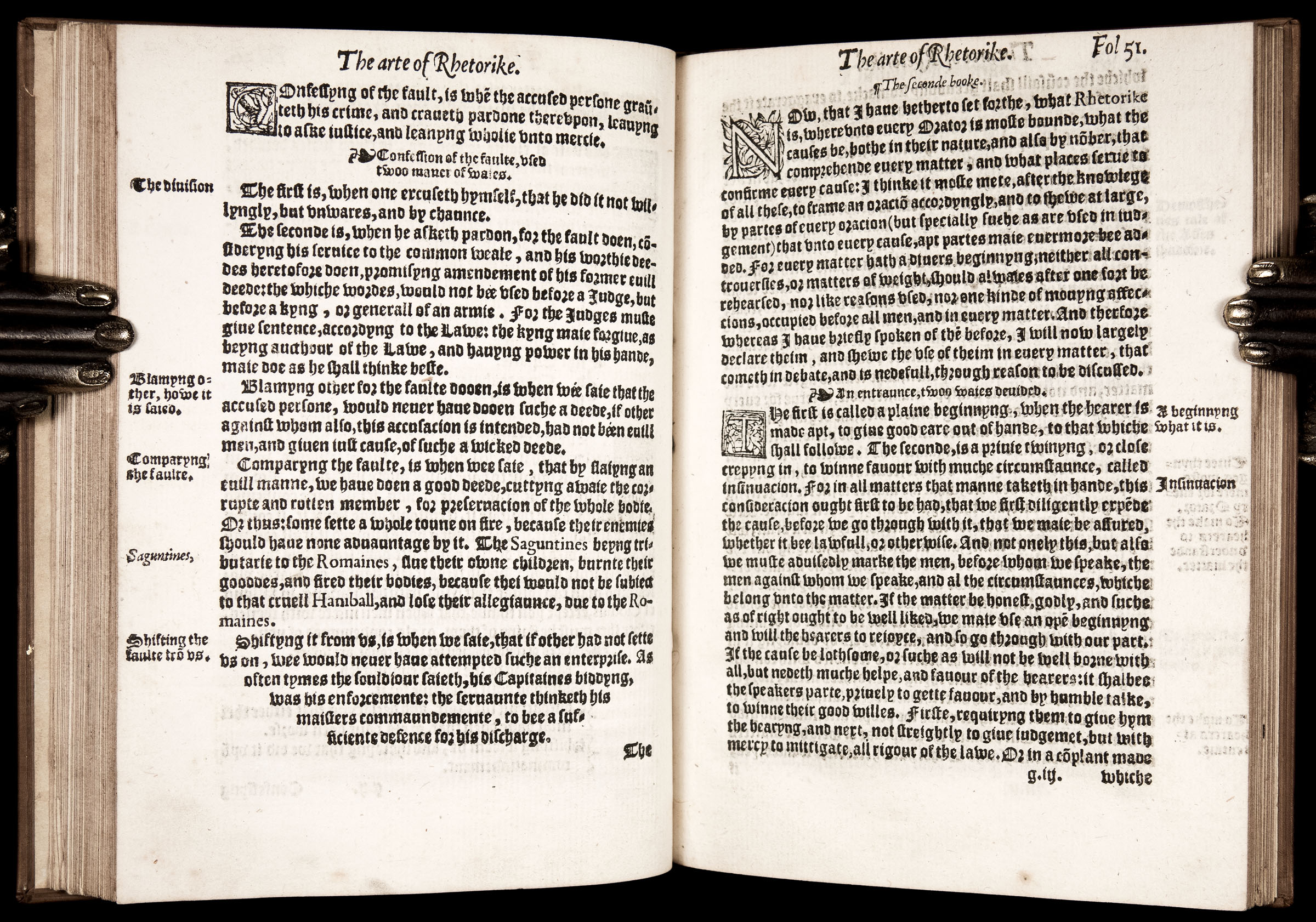

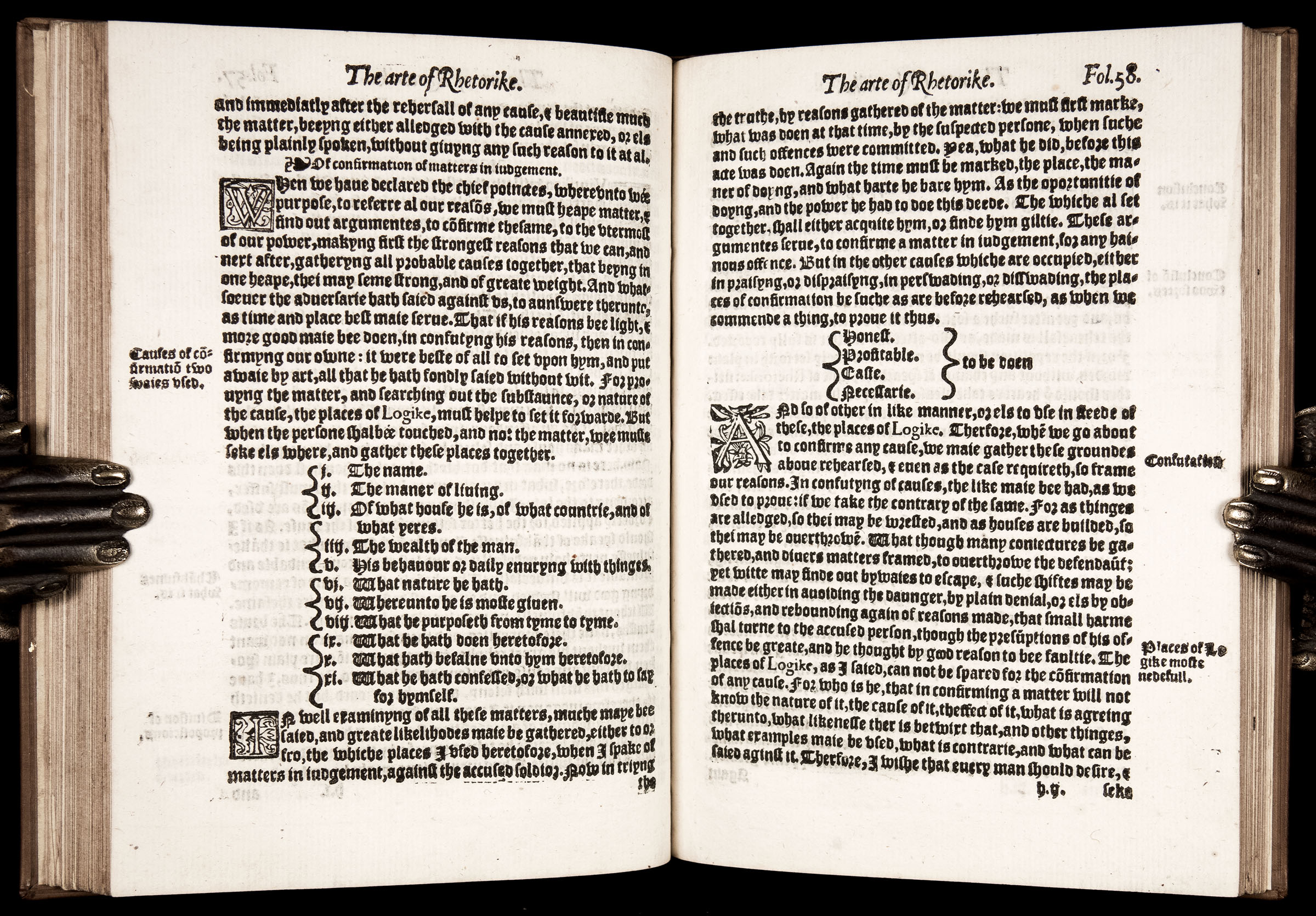

Fourth or fifth Edition of the book considered to be the earliest systematic work of literary criticism in the English language. This and all other 16th-century editions are extremely rare.

Includes an English translation of a very long excerpt from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s Encomium Matrimonii under a section title “An Epistle to perswade a young ientleman to Mariage, deuised by Erasmus…” (ff.20v-32v), as an example of a deliberative oration.

This Important work (first published in 1553 as Arte of Rhetorique) helped developed a scholarly and respectable English style, based on classical principles, but also advocating for a simpler, clearer and more streamlined style, than was generally appreciated at the time. Wilson denounced pedantry of contemporary English writers and their use of "strange inkhorn terms,” and the use of French and "Italianated" idiom, which "counterfeited the kinges Englishe." Wilson’s approach largely took hold in the later 16th-century, and is believed to have influenced Shakespeare, particularly Shakespeare's development of such characters as Dogberry in play Much Ado About Nothing. and Timon in Timon of Athens (see e.g. Drake, Shakespreare and his Times, I, pp. 440-2, 472-4)

“The first English treatise to provide a comprehensive treatment of rhetoric [was Wilson’s] The Arte of Rhetorique (1553), which he intended for the benefit of the general public. Wilson derived some material from [Leonard] Cox's The Art or Crafte, but more importantly, Wilson's work […] was deeply informed by both Cicero's entire rhetorical corpus and Erasmus's educational writings. Through its numerous reprints and extensive English examples, Wilson's Arte of Rhetorique would profoundly affect not only the concepts of rhetorical theory but also sixteenthcentury English letter writing and literature in general.” (Marco Sgarbi (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, p. 905)

Thomas Wilson (1524–1581) was an English diplomat and judge who served as a privy councillor and Secretary of State (1577–81) to Queen Elizabeth I. He is remembered especially for his Logique (1551) and The Arte of Rhetorique (1553), which have been considered the first complete English works on logic and rhetoric, respectively.

Born the son of Thomas Wilson, a farmer, of Strubby, Lincolnshire. He was educated at Eton College under Nicholas Udall, and at King's College, Cambridge, where he joined the school of Hellenists to which John Cheke, Thomas Smith, Walter Haddon and others belonged. He graduated B.A. in 1546, and M.A. in 1549.

Wilson was an intellectual companion to the sons of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, especially with John, Ambrose, and Robert Dudley. When the Dudley family fell from power in 1553, he fled to the Continent. He was with Sir John Cheke in Padua in 1555–1557, and afterwards at Rome, whither in 1558 Queen Mary wrote, ordering him to return to England to stand his trial as a heretic. He refused to come home, but was arrested by the Roman Inquisition and tortured. He escaped, and fled to Ferrara, but in 1560 he was once more in London. Wilson became Master of Requests and Master of St Katherine's Hospital in the Tower in 1561 and entered parliament in January 1563 as MP for Mitchell, Cornwall. In 1571 and 1572 he was elected MP for London. From 1574 to 1577, Wilson, who had now become a prominent person in the diplomatic world, was principally engaged on embassies to the Low Countries, and on his return to England he was made a privy councillor and sworn secretary of state; Francis Walsingham was his colleague. In 1580, despite his being not in holy orders, Queen Elizabeth appointed Wilson Dean of Durham.

“It is Thomas Wilson, rather than Leonard Cox, who deserves the title of the first English rhetorician. […] Wilson’s Arte of rhetorique (1553, 1560) is the first art of English rhetoric: a treatise that takes for granted its interest and value as an analysis of vernacular norms and practices. Where Cox envisions an audience of schoolboys or poor Latinists, Wilson's treatise addresses itself on its title page to 'all suche as are studious of Eloquence'. 'Boldly... may I aduenture, and without feare step forth to offer that... which for the dignitie is so excellent, and for the use so necessarie.’ Wilson proclaims in his Prologue to the revised and expanded edition of 1560. This boldness has much to do with Wilson's ability to imagine a mutually enriching relationship between eloquence and Englishness. […] [He] courts an educated readership, prefacing the first edition of his Arte with Latin poems by university men. He dedicates both editions to his patron John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick, whose 'earnest wish' [was] that he 'might one day see the precepts of rhetorique set forth in English’. […] Indeed, for Wilson, Dudley's Englishness is a rhetorical asset: he anticipates a time when the 'perfect experience, of manifolde and weightie matters of the Commonweale, shall haue encreased the Eloquence, which alreadie doth naturally flowe’ in Dudley to such an extent that his own Arte will be 'set to Schoole' in Dudley's home, 'that it may learn Rhetorique of... daylie talke'.

“This fancy, that eloquence might be schooled by an English nobleman's 'daylie talke', upends Thomas Elyot's conception of England as a realm where persuasion was never used, and it offers a radical challenge to Roger Ascham's conviction that the 'trewe Paterne of Eloquence' must be sought not in 'plaine naturall English', but in 'the unspotted proprietie of the Latin tong at the hiest pitch of all perfitness' (The Scholemaster, p.146). Like Elyot and Ascham (whose friend and peer he was), Wilson identified with the cause of English humanism, but in The Arte of Rhetorique, he is at pains to expose what he sees as the unintended cost of that movement's lack of faith and interest in the mother tongue: a slavish devotion to Latin and Greek that has prevented English from fulfilling its own potential for eloquence.

“Indeed, the chief objects of concern in Wilson's Arte are not the unlearned, ineloquent English, but those among them who have forsaken common talk for the pleasures of private books and foreign travel: modish young men so enamoured of foreign literature that they mistake foreignness itself for a linguistic virtue […]. Wilson's sense of the vernacular thus depends on the same equation of geography and language that, for Elyot, condemns England to rhetorical mediocrity: he too treats English as an insular tongue, remote from Latin, Greek, and the modern Romance languages. But Wilson draws a strikingly different conclusion from that equation; for him, English is not the rude speech of a rude country, but the uncorrupted tongue of a nation whose insularity and remoteness have preserved it from moral degradation, political coercion, and 'oversea language'. Its peculiar geography is not the impediment to England's literary ambition, but the condition necessary for its fulfilment, the guarantee of its linguistic purity. “ (Andrew Hadfield (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of English Prose 1500-1640, p.10-12)

Bibliographic references:

STC 25803; ESTC S469698; Lowndes p.2946.

Physical description:

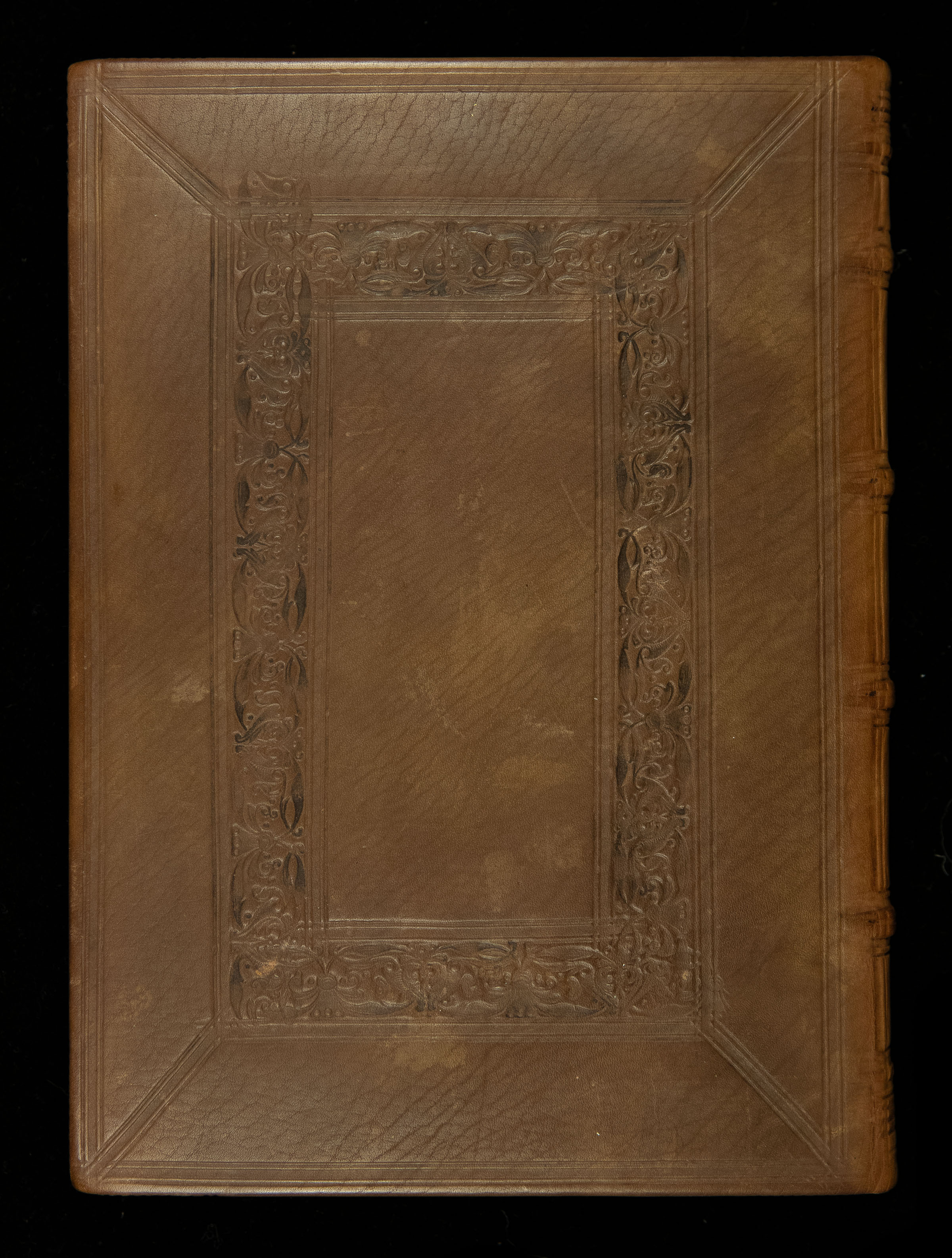

Quarto; textblock measures 185 mm x 133 mm. Bound in fine modern blind-paneled brown polished calf in imitation of 16th-century style (attributed to Bernard Middleton).

Foliation: [8], 113, [3] leaves (forming 248 pages). Signatures: A8 a-o8 p4). COMPLETE.

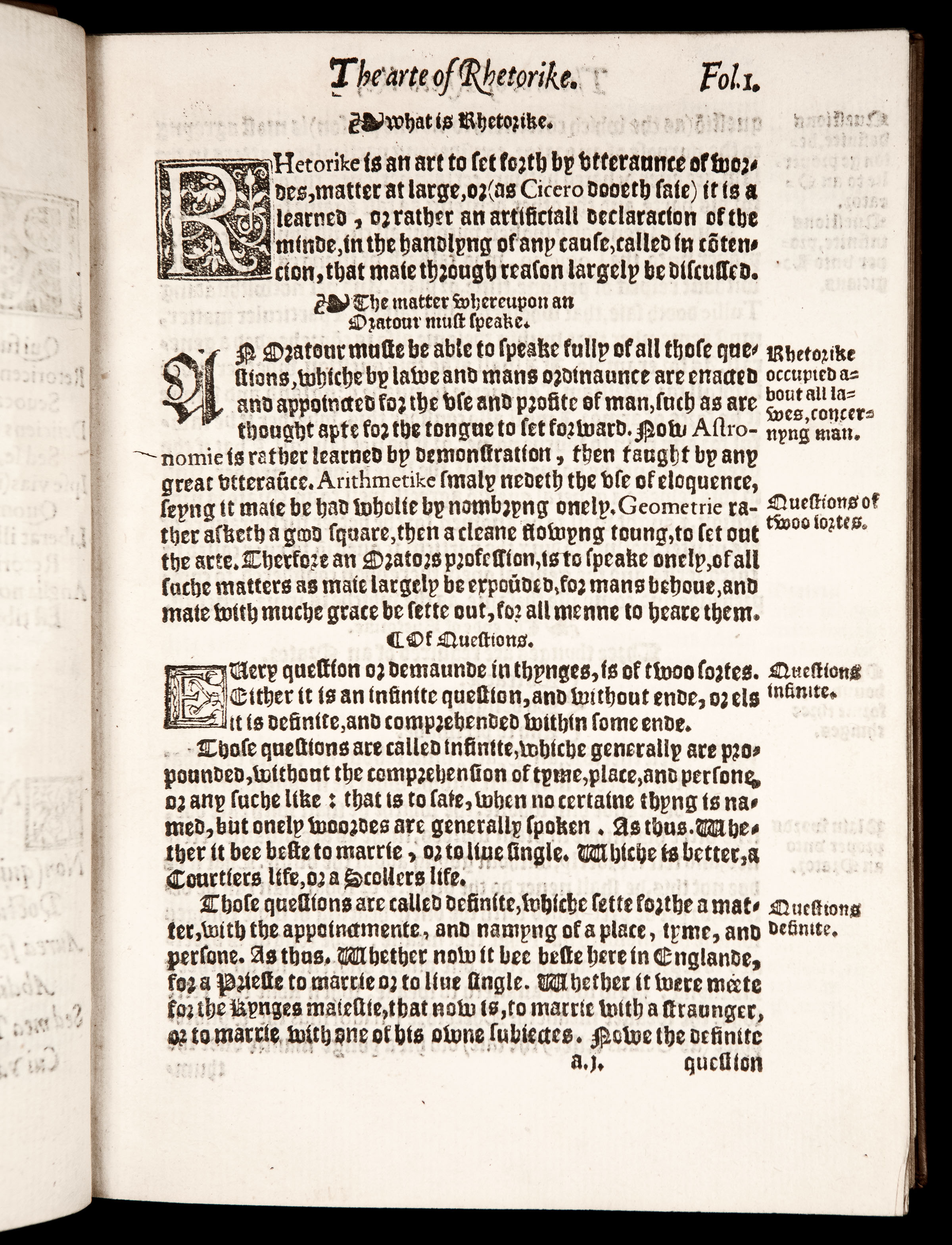

Title within a fine historiated woodcut border (McKerrow & Ferguson 117) flanked by figures of Moses and Aaron, and with two devils (in bottom compartment) and other grotesques.

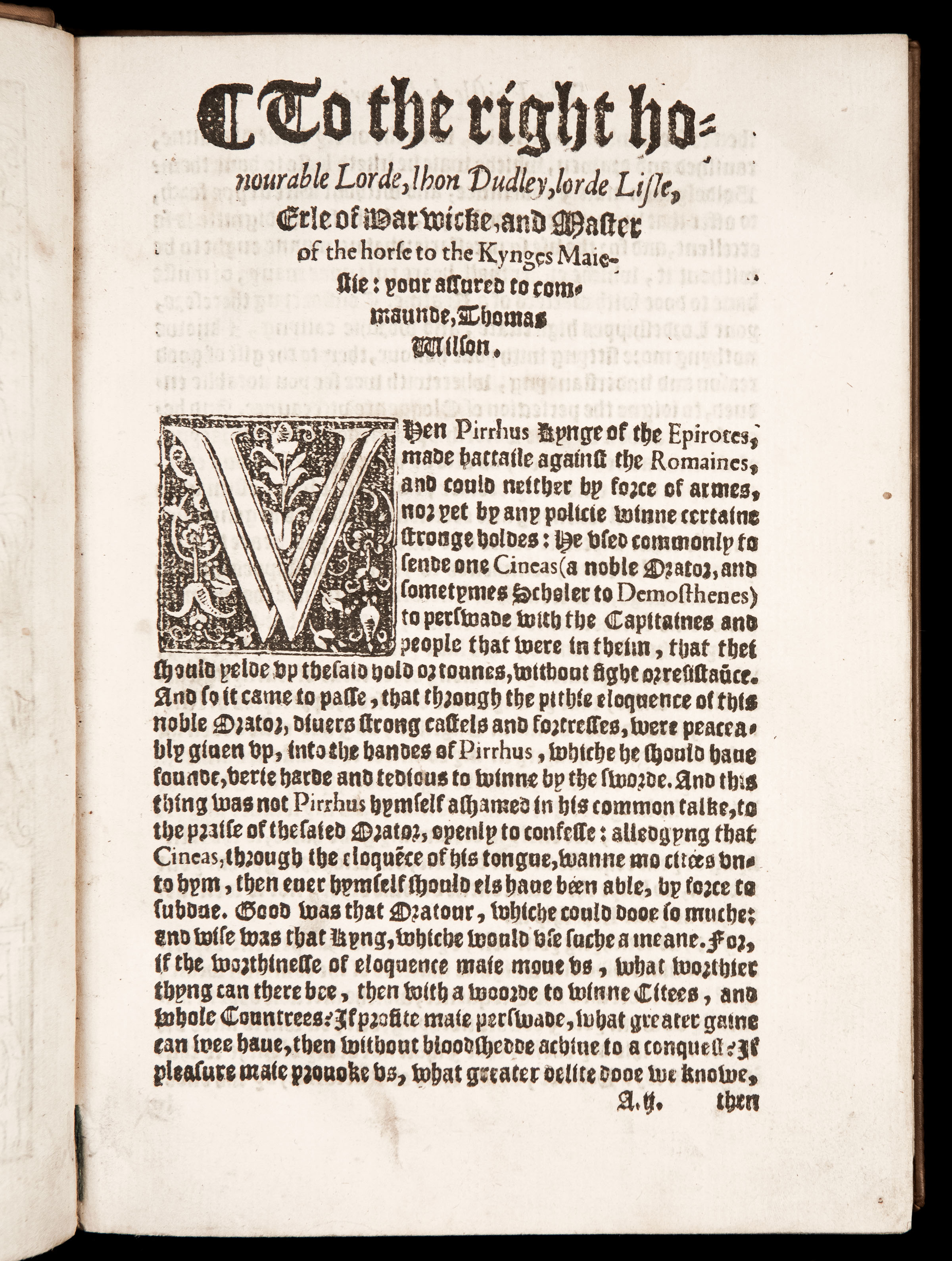

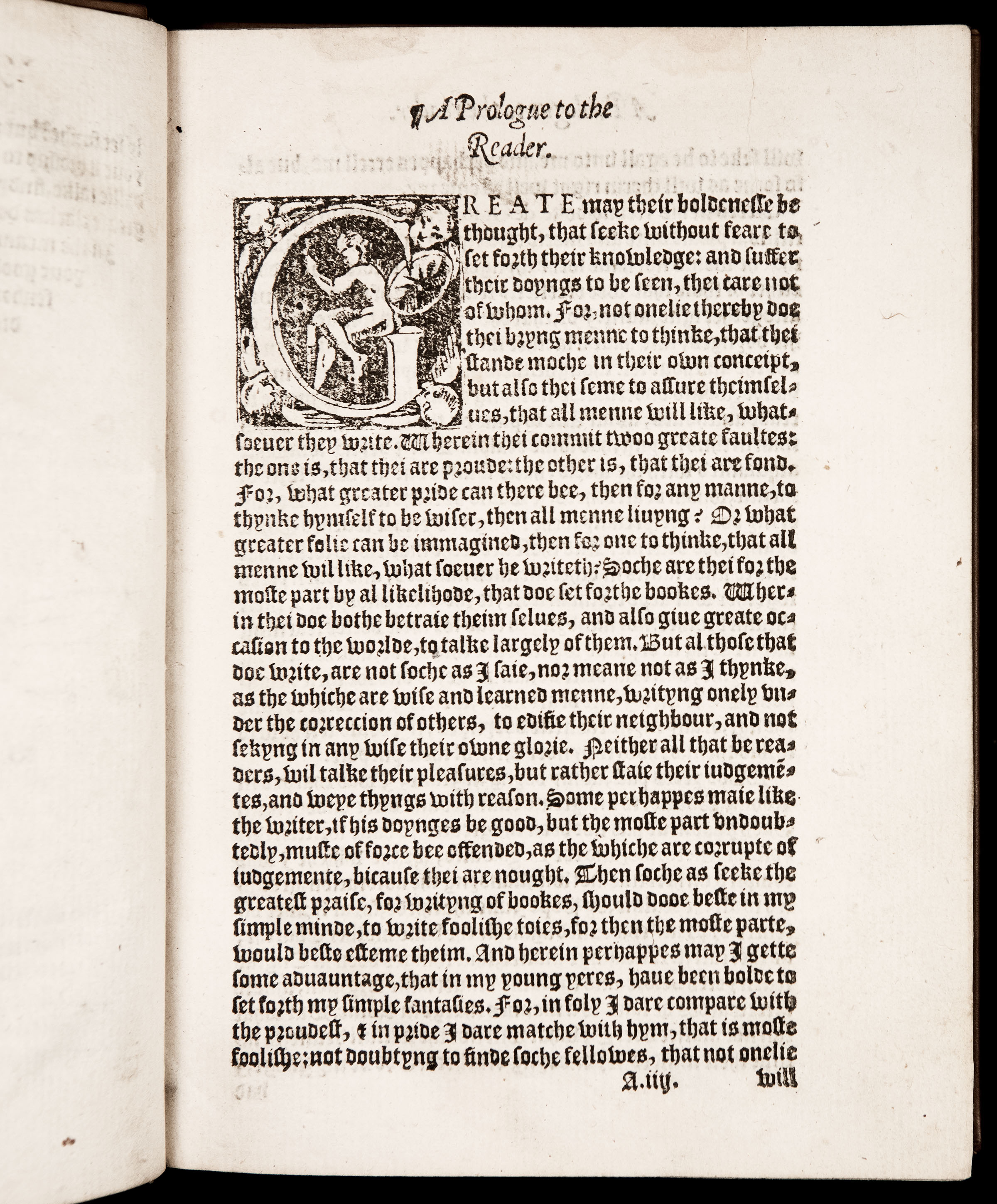

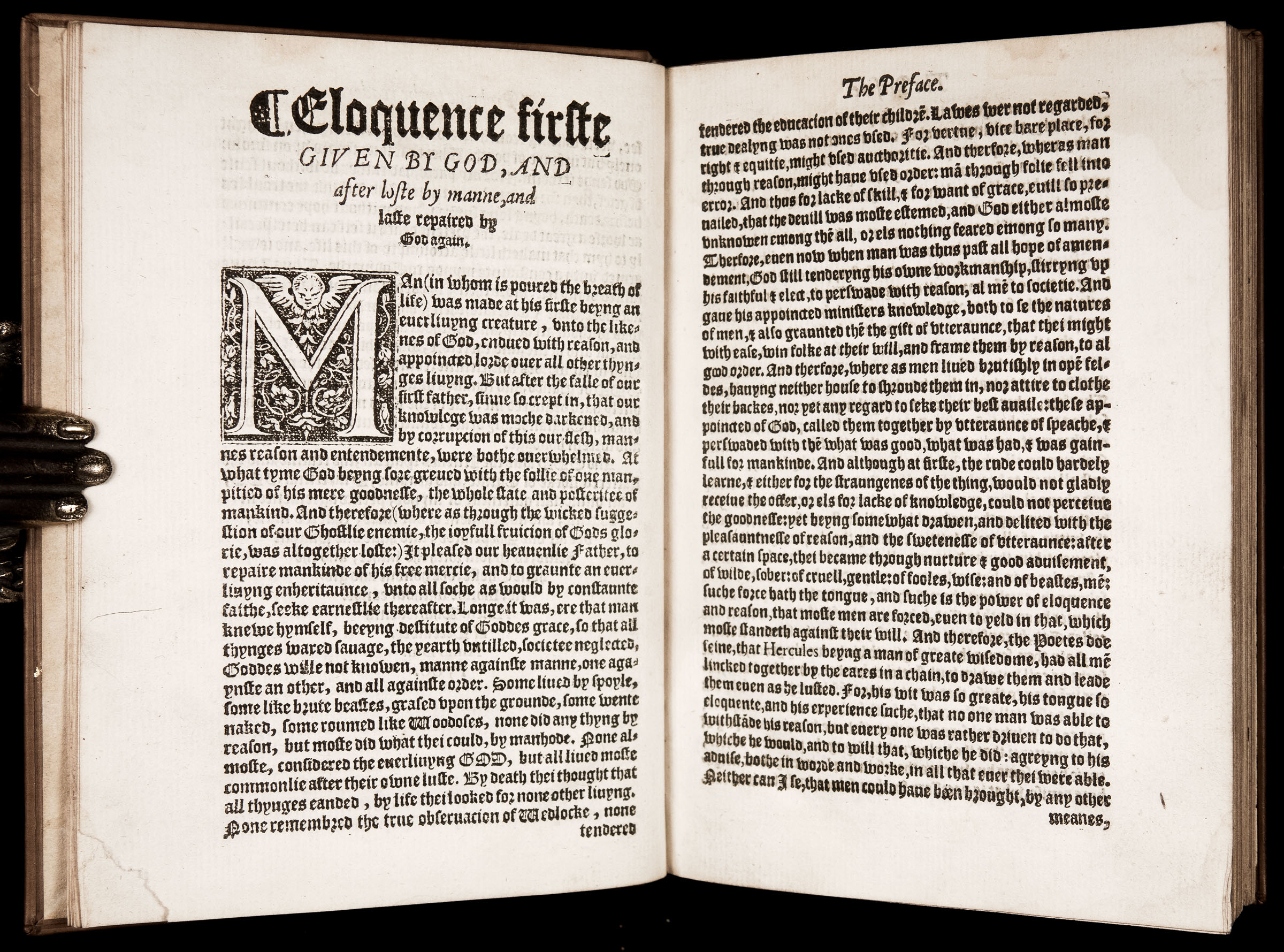

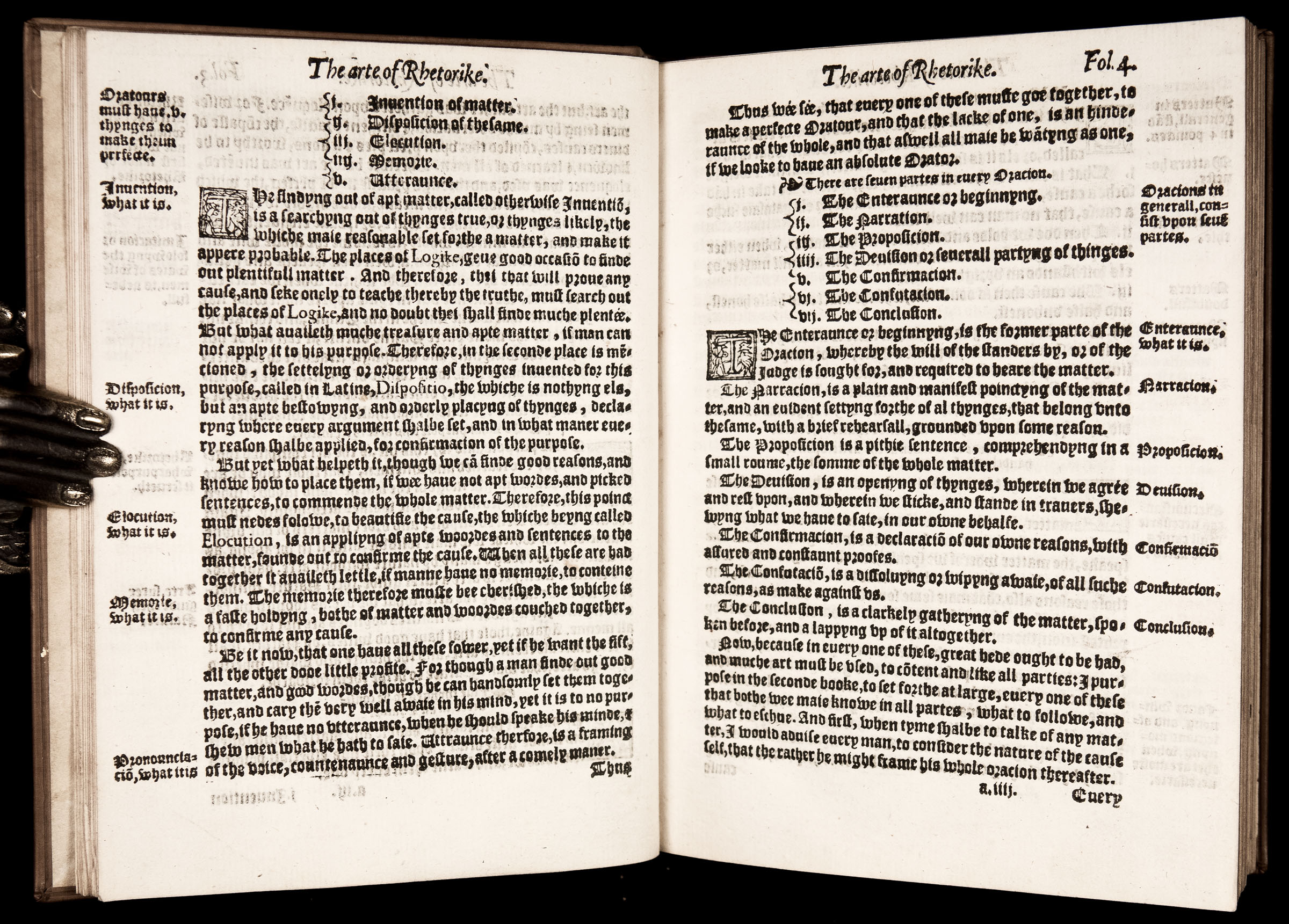

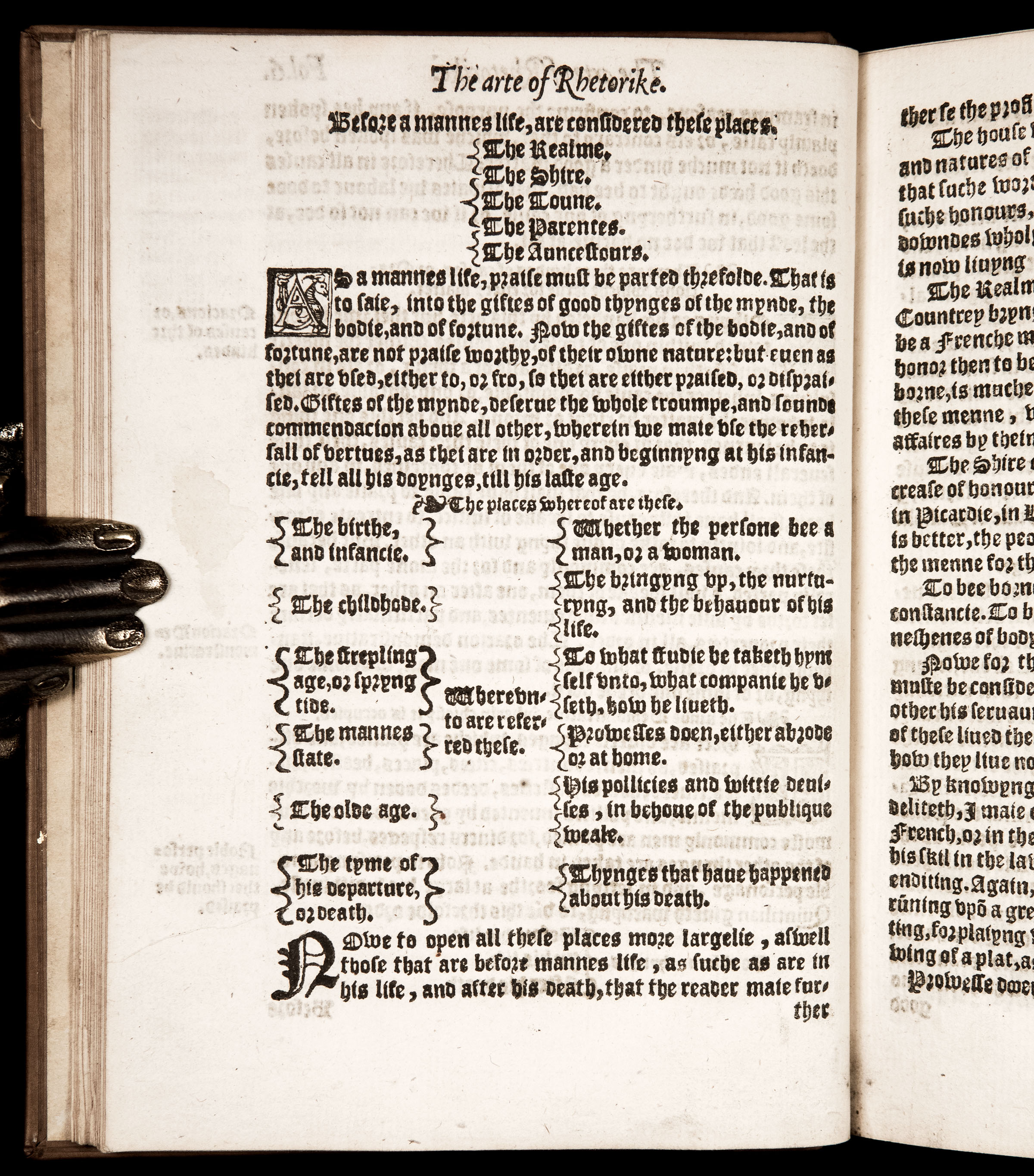

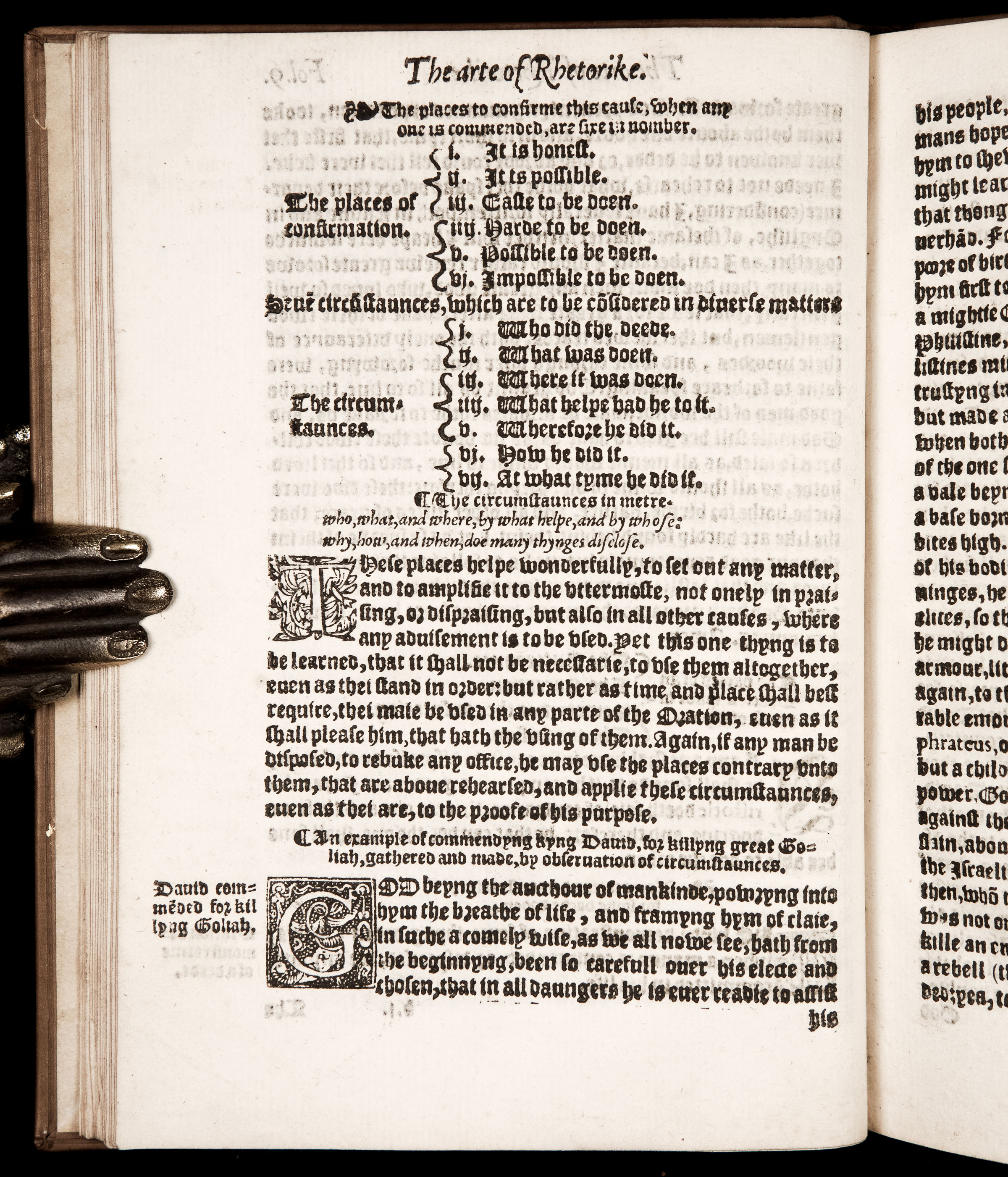

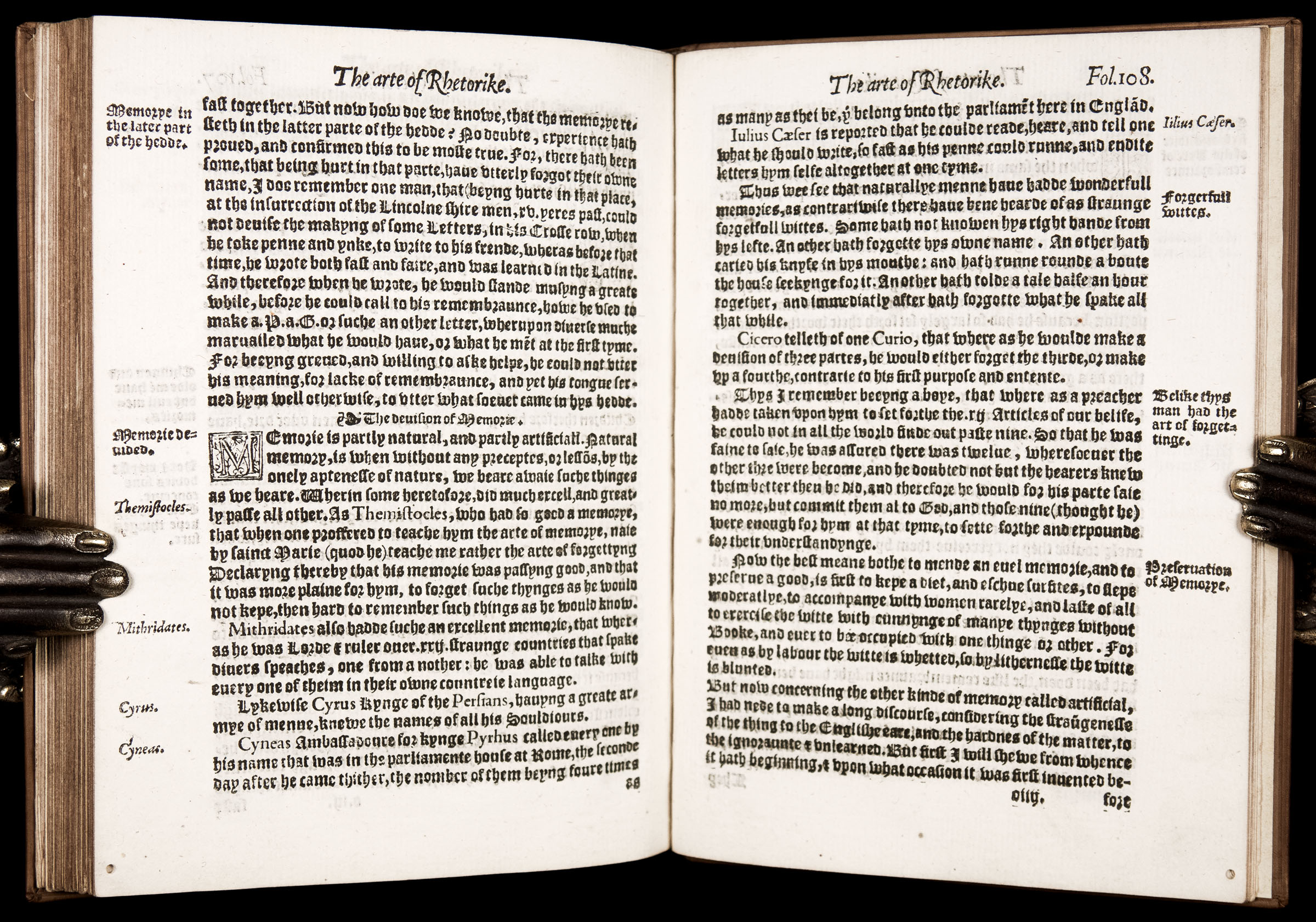

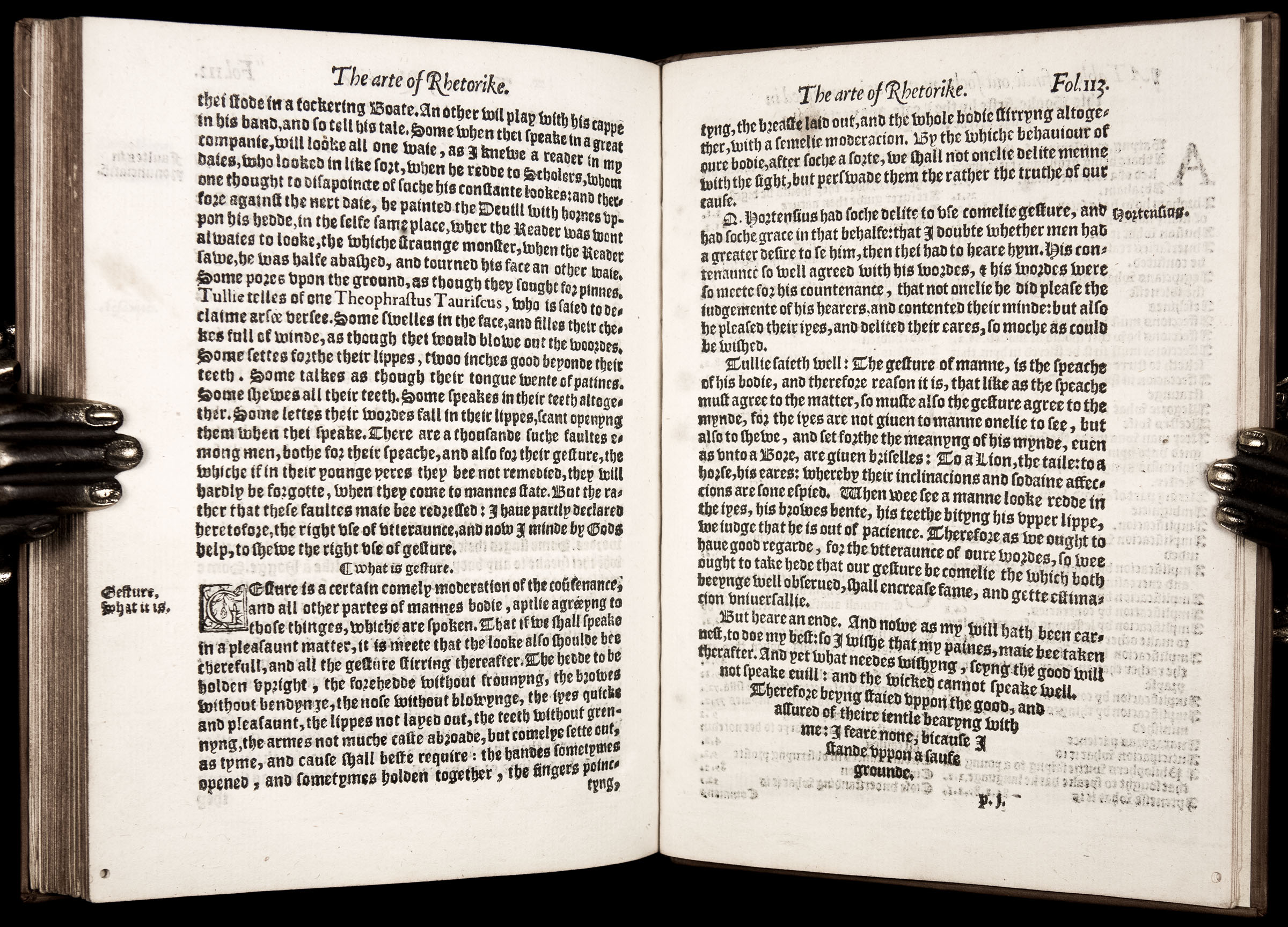

Text printed in black letter (English gothic type); Latin words in roman or italic. Numerous woodcut initials of various sizes.

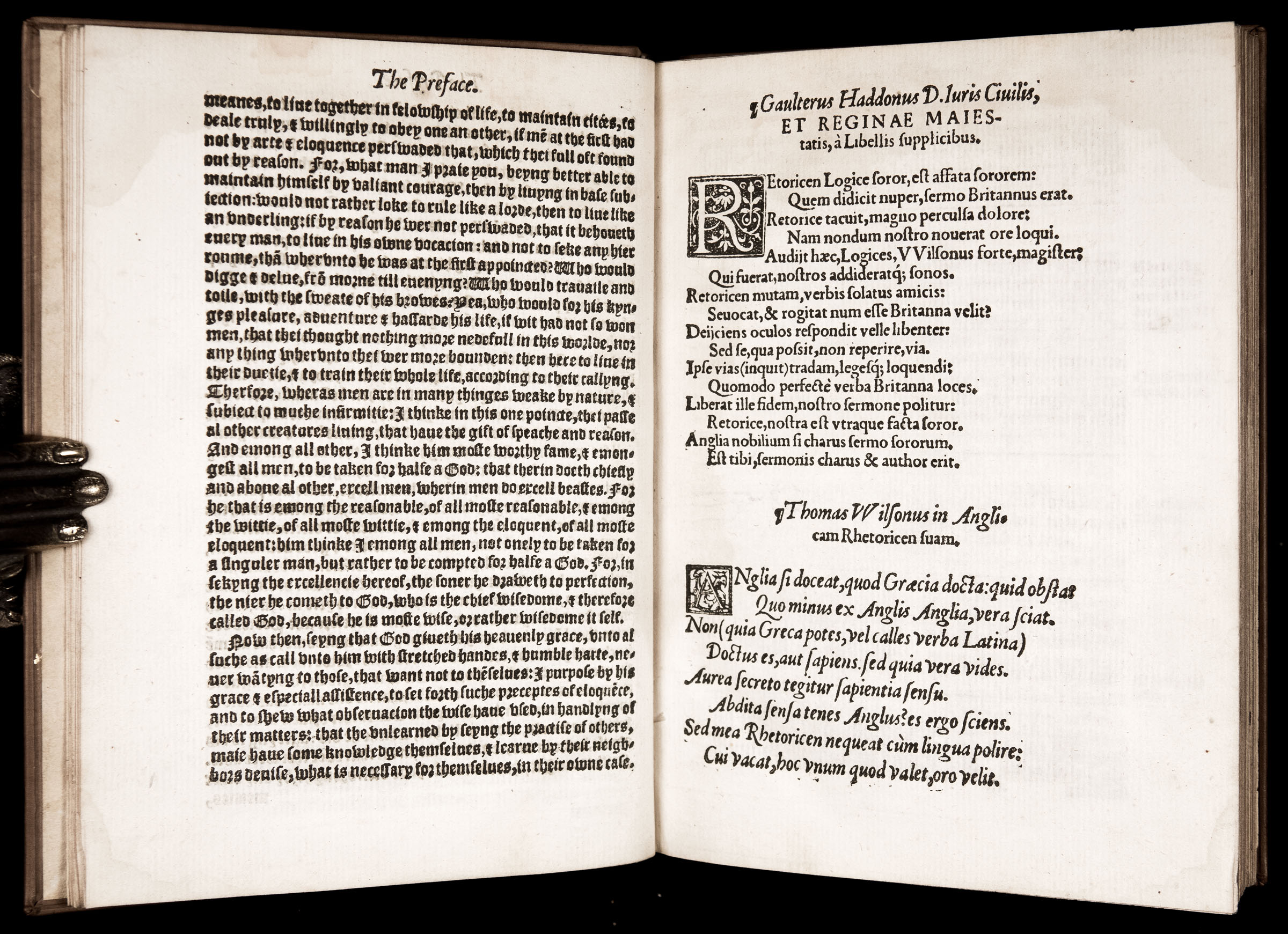

Preliminaries include a dedicatory epistle by Wilson addressed to John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick (leaves A2r-3r); a Prologue to the Reader (leaves A4r-6r); a preface titled “Eloquence firste given by God…” (A6v-7v), and two laudatory poems on Wilson in Latin (A8r, verso blank).

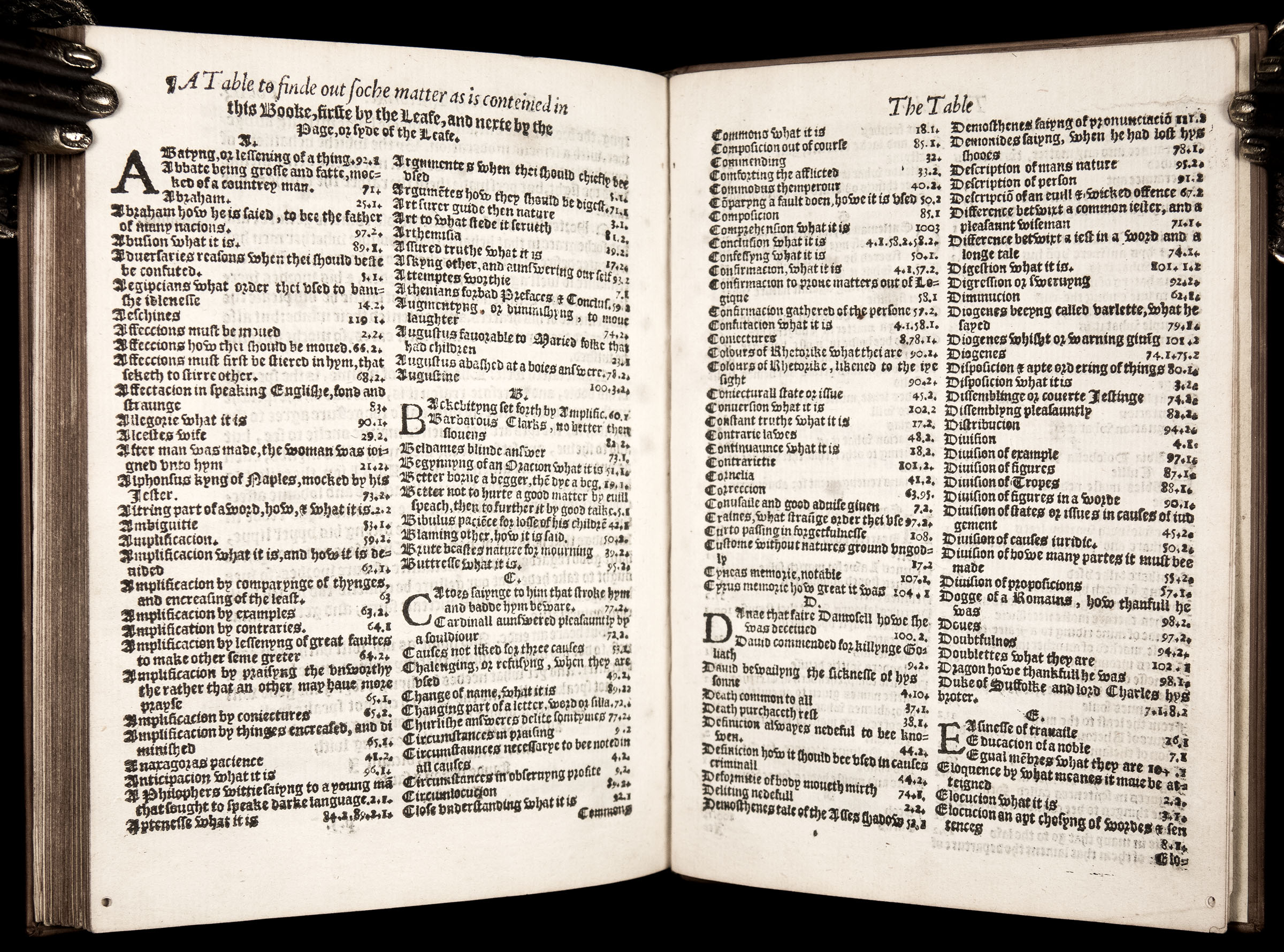

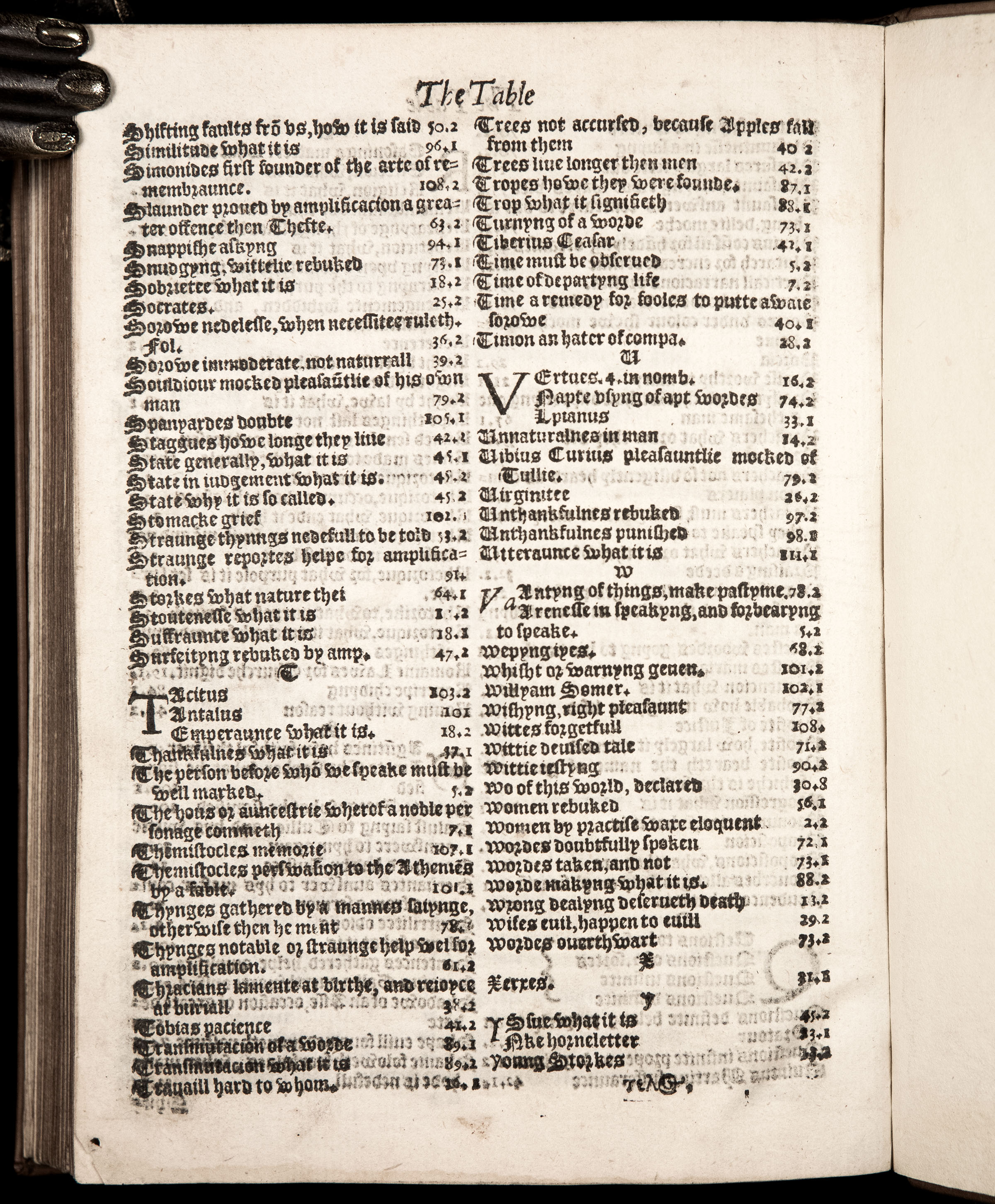

Includes an alphabetical Index (printed in double columns) at the end (leaves p1v-4v).

Provenance:

A clipping from a modern catalogue (loosely laid in) states that the binding was made by Bernard Middleton, MBE (1924 – 2019), a preeminent British restoration bookbinder. Referred in the trade as "The Great Man", he was regarded as one of the foremost book craftsmen and trade historians of modern times, lecturing and teaching in Europe and Americas. He authored two major works, ‘A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique’ (1963) and ‘The Restoration of Leather Bindings’ (1972), which became essential reading for professional bookbinders and collectors. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in 1951 and, in 1986, was awarded an MBE for services to bookbinding. His bindings may be seen in the British Library, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Royal Library, Windsor, and other major libraries worldwide.

Condition:

Very Good+ antiquarian condition. Complete. Binding slightly rubbed, and a bit faded in places. Internally with occasional light browning, some light soiling (mostly marginal); a few leaves with light marginal water-staining, Preliminary leaf A6 with a small blank piece of the bottom fore-corner torn off (text completely unaffected). A tiny, harmless marginal wormhole at the bottom fore-corner towards the end of the volume (far from any text, no loss). Some see-through affect of type on a few pages. A very clean, solid, well-margined example of this rare and important early Elizabethan imprint.