[Early Printing - Incunabula - Basel] [Roman Catholic Church - Moral Theology - The Ten Commandments]

[Occult and Esoterica - Witchcraft and Demonology]

Johannes Nider

Praeceptorium divinae legis,

sive Expositio decalogi

$6,950

Basel: [Johann Amerbach], 1481.

Second Basel edition. Text in Latin. RARE! ISTC locates ONLY 3 (!) COPIES of this edition in the US libraries.

This is a very attractive, wide-margined and unrestored example (with a superbly illuminated initial and border on the opening page) of this rare incunable edition of Nider’s influential work on the precepts of the Divine Law as expressed in the Ten Commandments, which includes some interesting material on witchcraft and demonology.

Its author, Johannes Nider, an important early 15th-century Dominican theologian and canonist, was an avid reformer, and a staunch opponent of the Hussites, witchcraft, etc. Nider’s Praeceptorium, which enjoyed great popularity in the later Middle Ages, offers a comprehensive interpretation of the Decalogue for confessors and preachers.

“The formation of conscience is a key concern of Johannes Nider. As he himself says in the prologue, Nider wrote his most extensive work, the Praeceptorium divinae legis, on the request of his confreres for the debitis exercitijs of preachers and confessors. […] The entire Praeceptorium revolves around the question of when an act is to be deemed as having transgressed the boundary of a mortal sin, i.e. to determine where the path to eternal life has been left and when a sin can still be regarded as venial.” (T. Brogl, ‘Johannes Nider’s Idea of Conscience,’ in S. Müller, C. Schweiger (eds.): Between Creativity and Norm-Making, p.65)

It should be noted that Nider’s lifelong preoccupation with matters of witchcraft, most evident in his Formicarius, manifests itself in Praeceptorium as well. Nider’s Praeceptorium quickly was a significant influence among the 15th- and 16th-century writers on witchcraft, including the most famous works on the subject: the infamous “Hammer of Witches” (Malleus Maleficarum, 1486), where Nider’s Praeceptorium is cited several times, and Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), which also contains references to the Praeceptorium.

“Johannes Nider INCLUDED A SUBSTANTIAL AMOUNT OF DEMONOLOGY in the commentary on the first Commandment in his Praeceptorium, blending topics like metamorphosis, transvection, demonic trickery and maleficium [witchcraft] with a lengthy amplification of the Thomistic taxonomy of superstitions.” (Stuart Clark, Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, p.498)

“The sections of Formicarius that dealt with dreams, visions, apparitions and witchcraft were also inserted into Nider's commentary on the Ten Commandments, The Praeceptorium divinae legis. Finished about the same time as the Formicarius, it was even more widely read with seventeen printed editions before 1500.” (Yvonne Owens, Abject Eroticism in Northern Renaissance Art, p. 128

“The Dominican J. Nider in his Praeceptorium divinae legis recorded the names of those who had contravened the first commandment by superstitious acts and beliefs. Among them were those individuals who thought they could be transported to the conventicles of Herodias, and […] women who 'during the Ember Days, out of their senses, boasted of having seen the souls in purgatory and of many other fantasies'. After these women recovered from their swoons, they related extraordinary things about souls in purgatory or in hell, about stolen or lost objects, and so forth. According to Nider these poor wretches had been deceived by the devil, and it was not surprising, if during their obscure trances they did not even feel the burn from the flame of a candle: the devil possessed them to such a point that they were aware of nothing, just like the victims of epilepsy.” (Carlo Ginzburg, The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults, p.39-40)

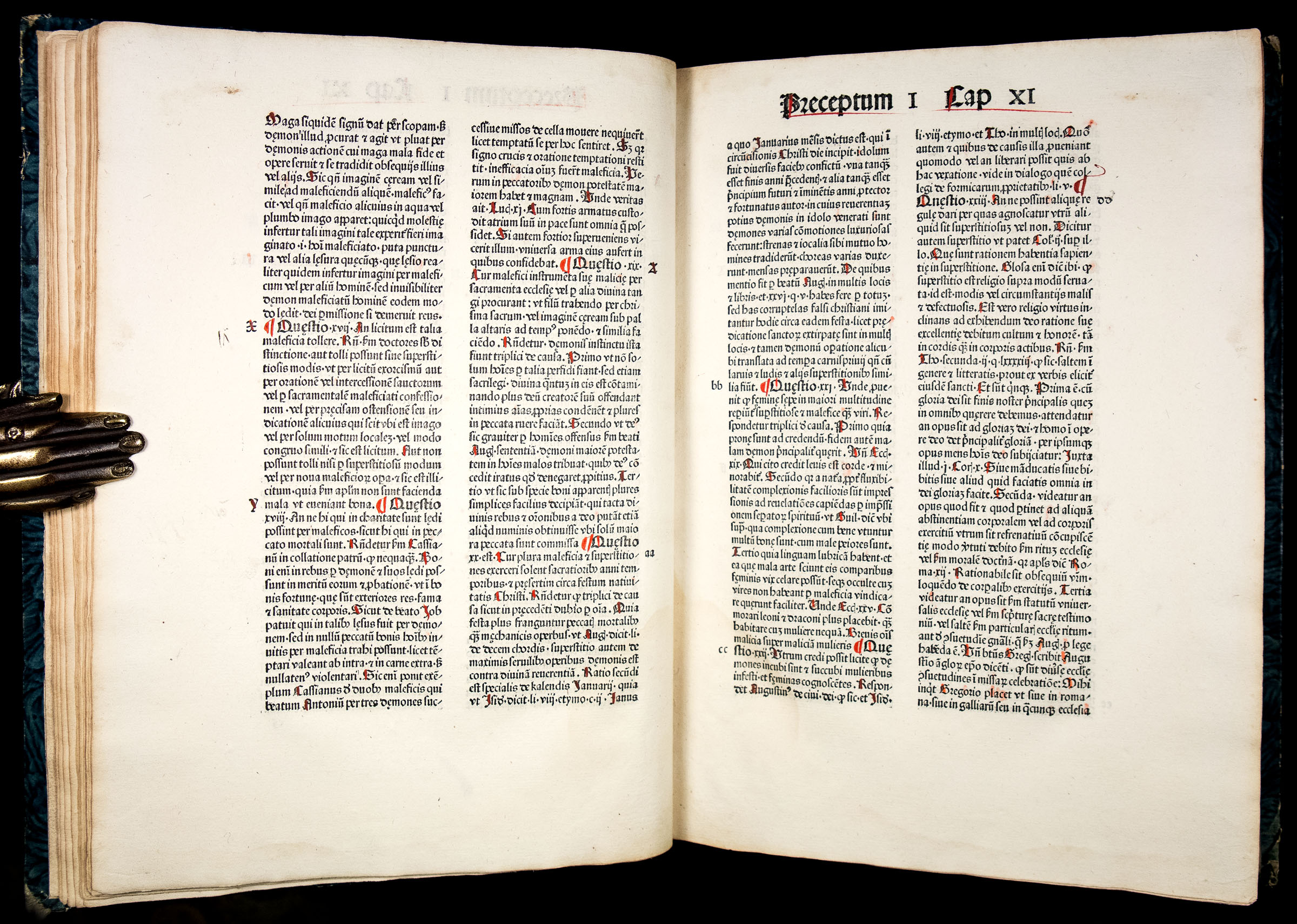

“In his Praeceptorium Nider raises the question whether there is any truth in what is said about the Mons Veneris, where certain people have commerce at their will with most beautiful women. To this is answered that William of Auvergne in De Universo lib. VIII say it is fictitious, […] though demons may deceive men in the ways described above (where Nider relates that a certain knight thought himself to enjoy a woman and on waking found himself in the mud, embracing the body of a dead beast). His [i.e. Nider’s] next question is as to the truth of what is said about a mountain near Bern, where in a cave are hidden men and women living most devoutly and having no communion with other faithful except on feast days to receive the sacraments, when they are transported through the air to certain priests known to them in the parishes. The answer is that this is the work of the demon, ‘as I have examined thoroughly, and a snare for the innocent […]. ‘I knew a devout nun whom the demon for a long while assailed, even visibly, and endeavored to lead her out from the monastery; but by the advice of prudent counselors she resisted and despised him’ [as related in this work, in] Primum Praeceptum, cap. XI.” (Arthur C. Howland, Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft, Vol. 1, p.265).

“Born sometime in the early 1380s in the small town of Isny in Swabia in what is now Southern Germany, Nider studied at Cologne and Vienna. He then attended the Council of Basel, where he began collecting many contemporary stories and examples of witchcraft that he would include in his Formicarius. […] In another work, the Preceptorium divinae legis (Preceptor of Divine Law), Nider attempted to provide a guide to various problems of religious belief and practice based on the Ten Commandments. In this work, he included some important sections on demonic magic and witchcraft under the heading of the First Commandment, which stated that one should not worship any deities before the one Hebrew, and later Christian, God. Demonic invocation, magic, and witchcraft were thought by medieval theologians to entail the worship of demons and thus constituted idolatry.

“One particularly important aspect of the witch stereotype that Nider developed was the presumption that women were more inclined toward witchcraft than men. In fact, Nider was the first learned authority to advance this position. Although he presented many examples of male witches, Nider described women as weaker than men in body, mind, and spirit. Thus, they were more prone to the seductions and temptations of the devil and submitted more quickly to his service than men. This basic line of argument would become much more pronounced in the extremely misogynist Malleus Maleficarum.” (J. Durrant & M. Bailey, Historical Dictionary of Witchcraft, p.143-4)

Johannes Nider (c.1380 - 1438) was a Dominican friar, a prominent theologian, diplomat, reformer, as well as a celebrated preacher throughout Germany and Switzerland at the beginning of the 15th century. Nider entered the Order of Preachers at Colmar and after profession was sent to Vienna for his philosophical studies, which he finished at Cologne where he was ordained. He gained a wide reputation in Germany as a preacher and was active at the Council of Constance. After making a study of the convents of his order of strict observance in Italy he returned to the University of Vienna where in 1425 he began teaching as Master of Theology. Elected prior of the Dominican convent at Nuremberg in 1427, he successively served as the vicar of the reformed convents of the German province. In this capacity he maintained his early reputation of reformer and in 1431 he was chosen prior of the convent of strict observance at Basel. He played an important role in the Councils of Constance (1414-18) and Basel (1431-49).

Nider became identified with the Council of Basel as theologian and legate, entrusted with the task of converting the Hussites of Bohemia. He made several embassies to the Hussites at the command of Cardinal Julian. Sent as legate of the Council to the Bohemians he finally succeeded in pacifying them. He journeyed to Ratisbon (1434) to effect a further reconciliation with the Bohemians and then proceeded to Vienna to continue his work of reforming the convents there. He resumed his theological lectures at Vienna in 1436 and was twice elected dean of the university before his death. As reformer he was foremost in Germany and welcomed as such both by his own order and by the Fathers of the Council of Basel.

Bibliographic references:

Goff N-208; Hain-Copinger 11793; Proctor 7561; BMC III 746; BSB-Ink N-168; GW M26911 Oates 2768. IBE 4133. IGI 6899.

Physical description:

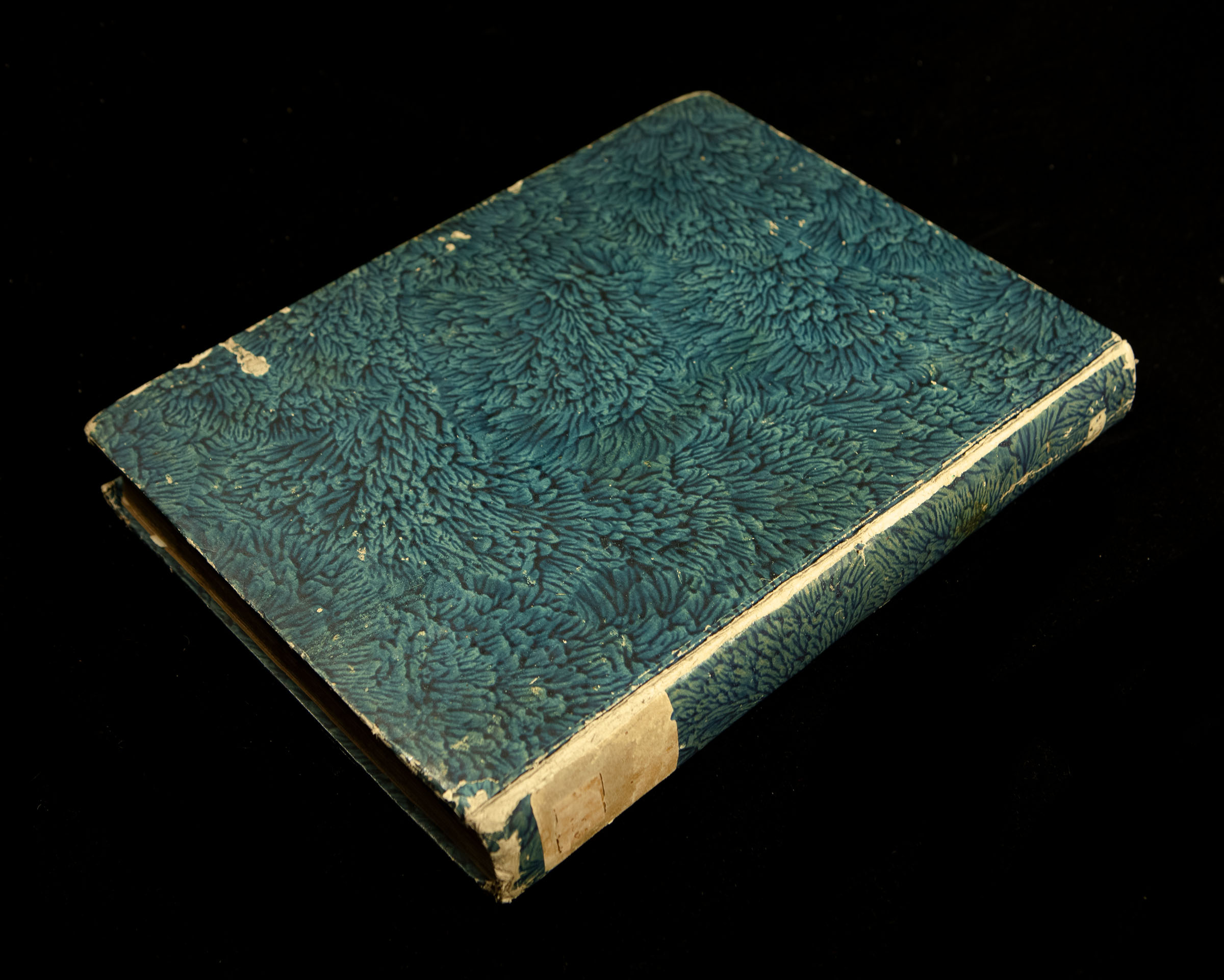

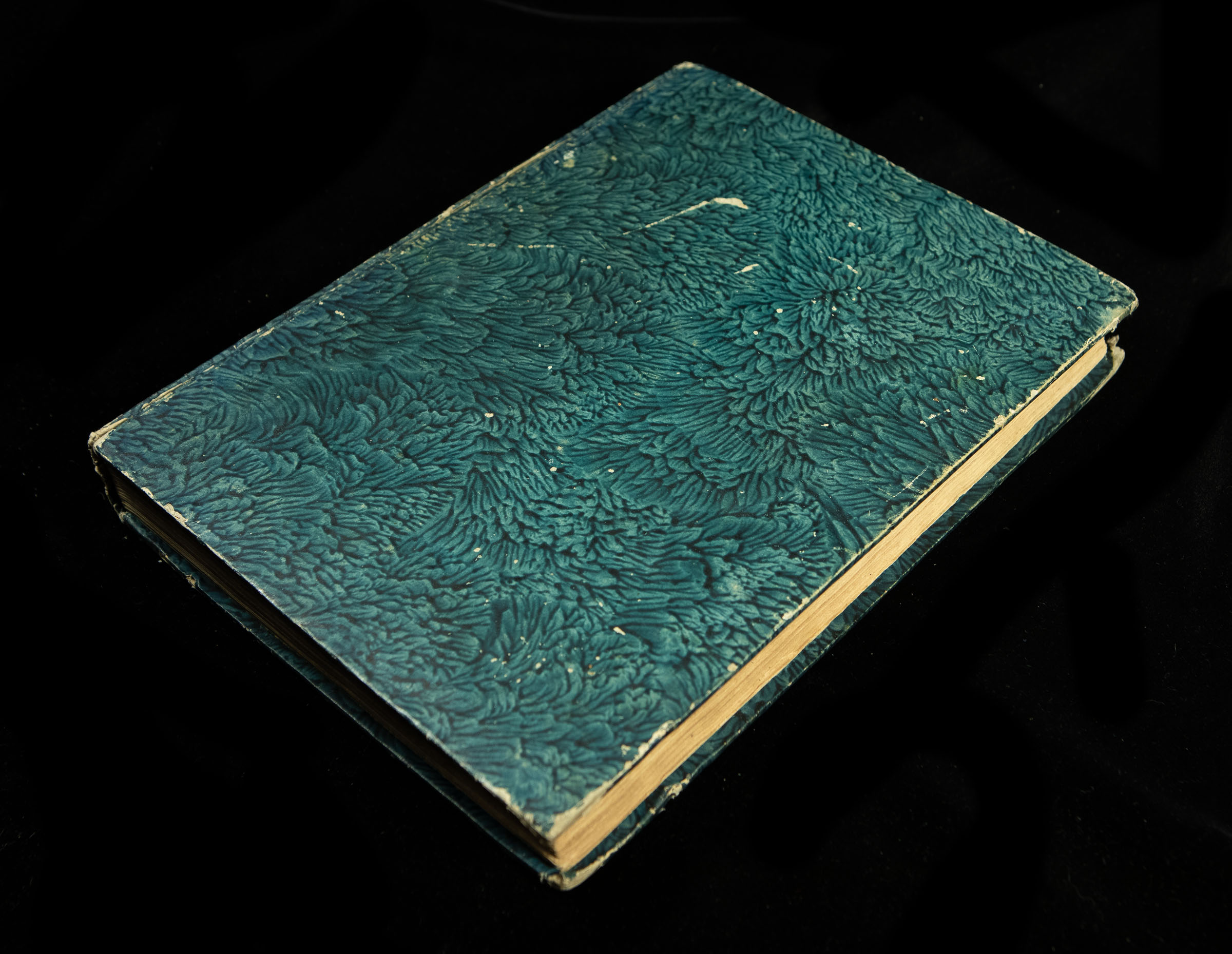

Chancery Folio; leaves measure approx. 293 mm x 210 mm. Bound in 19th-century blue marbled boards.

202 unnumbered leaves (forming 404 pages). Signatures: a–s10.8 t–y10. COMPLETE, including the integral blank a1, but bound without the alphabetical Index (additional quires A,B), like, e.g. the copy in Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol (Innsbruck, Austria).

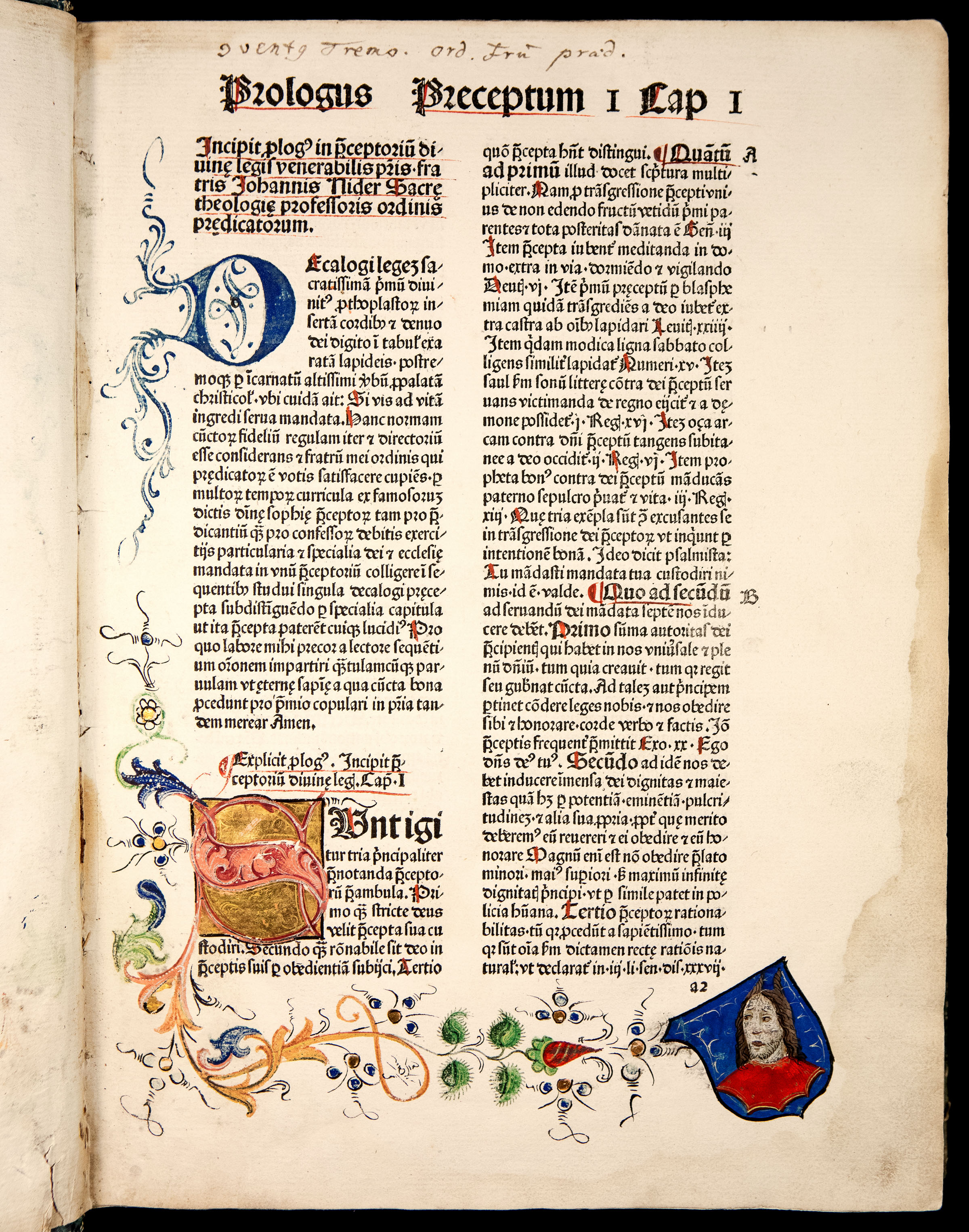

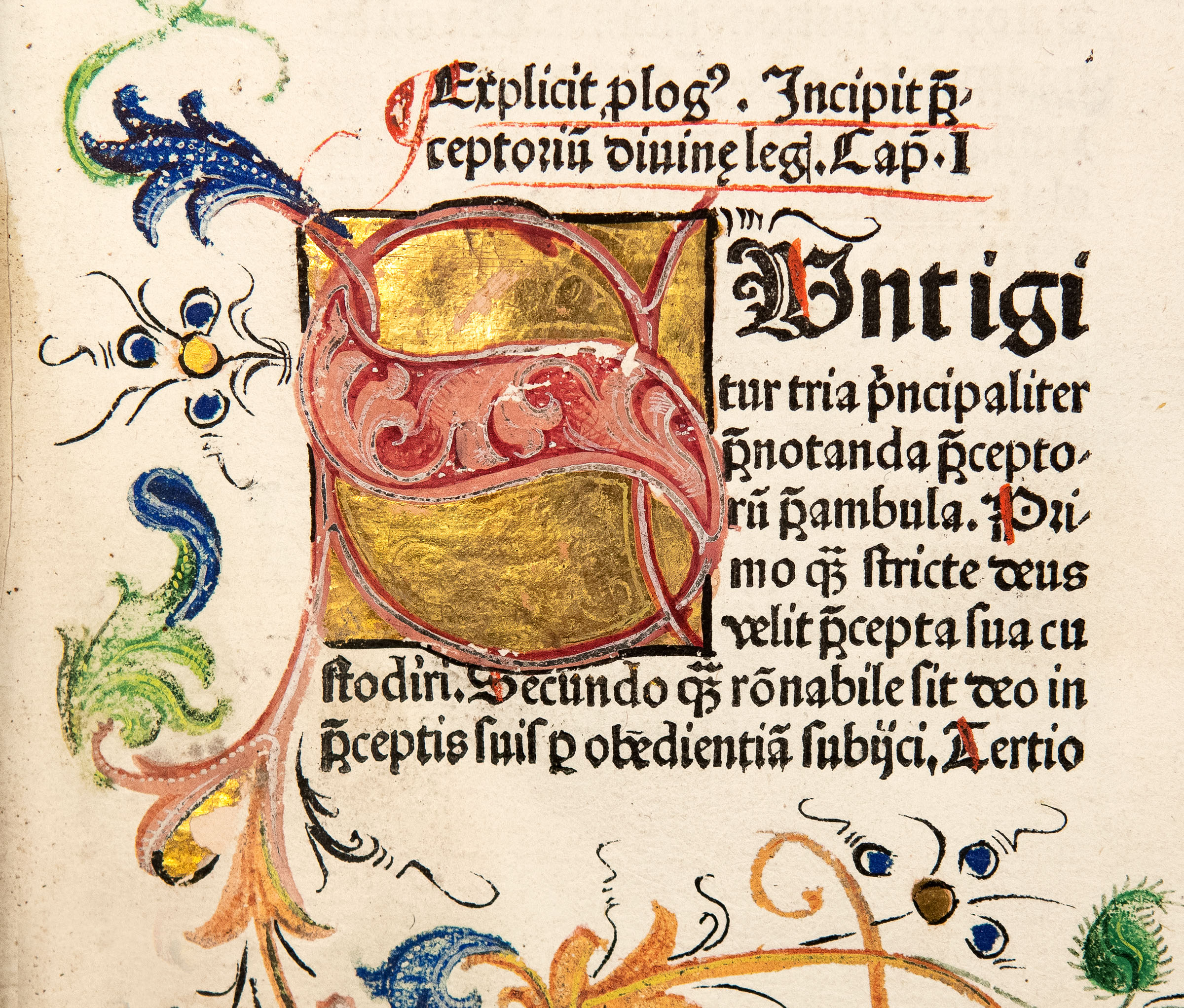

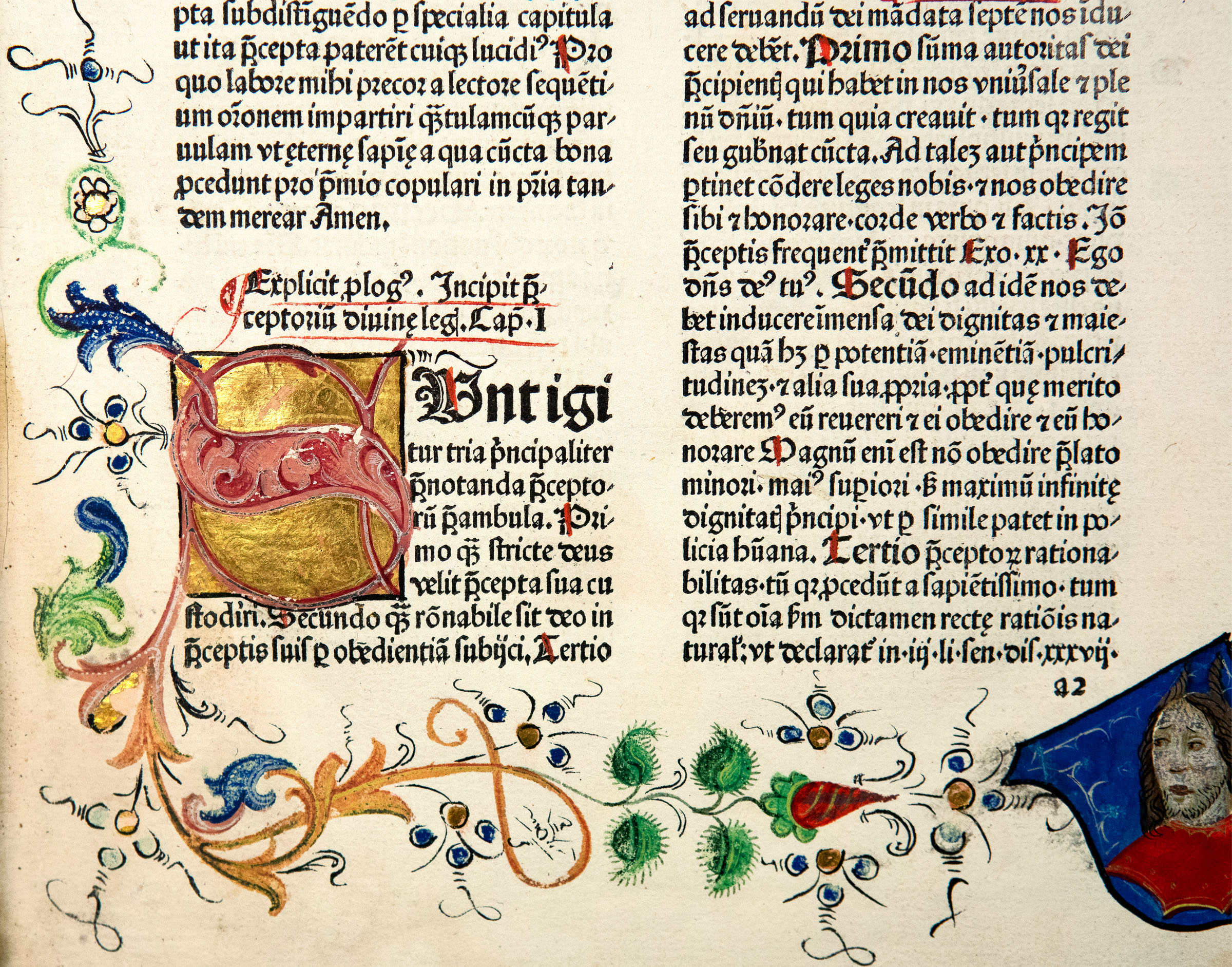

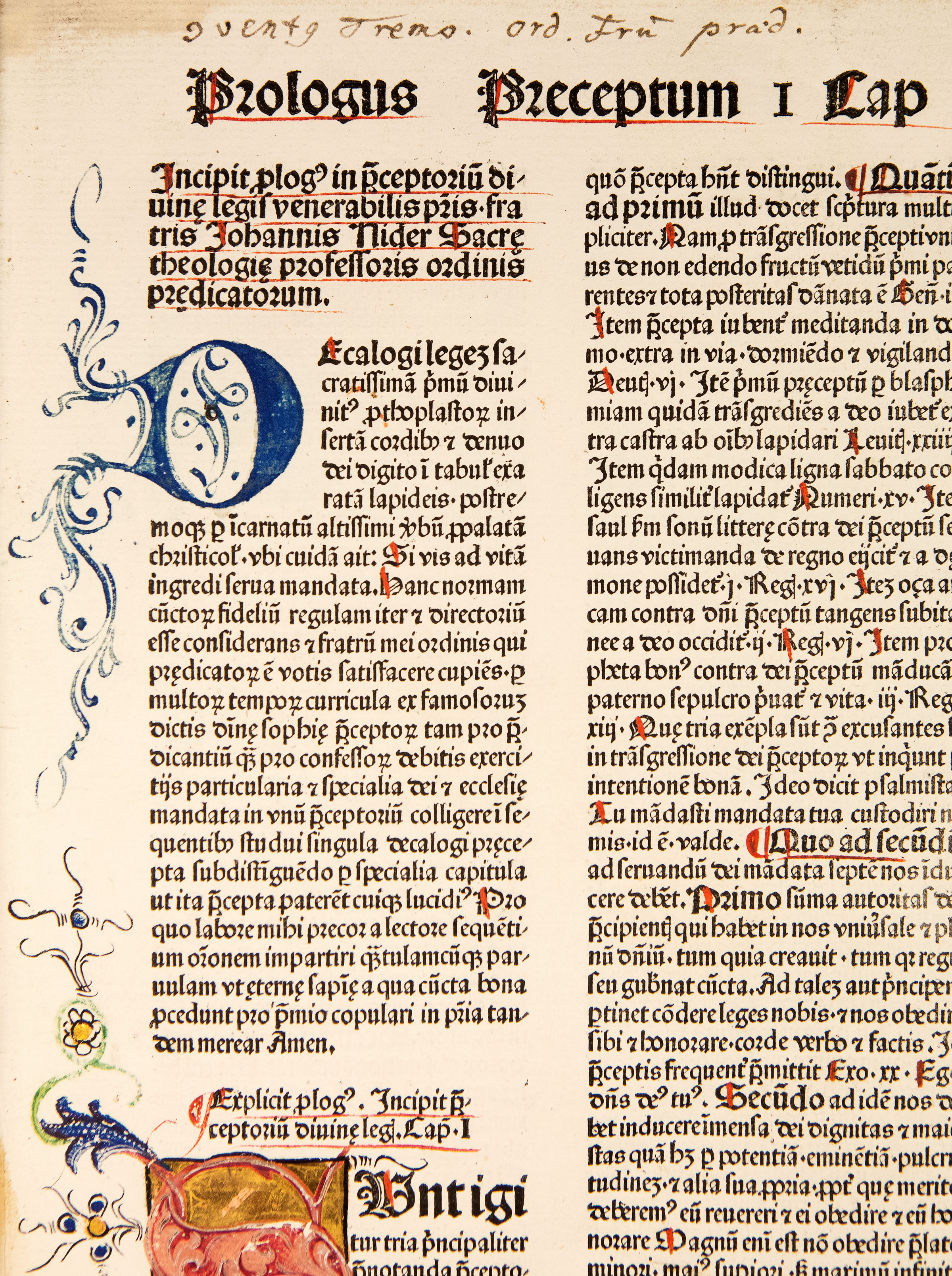

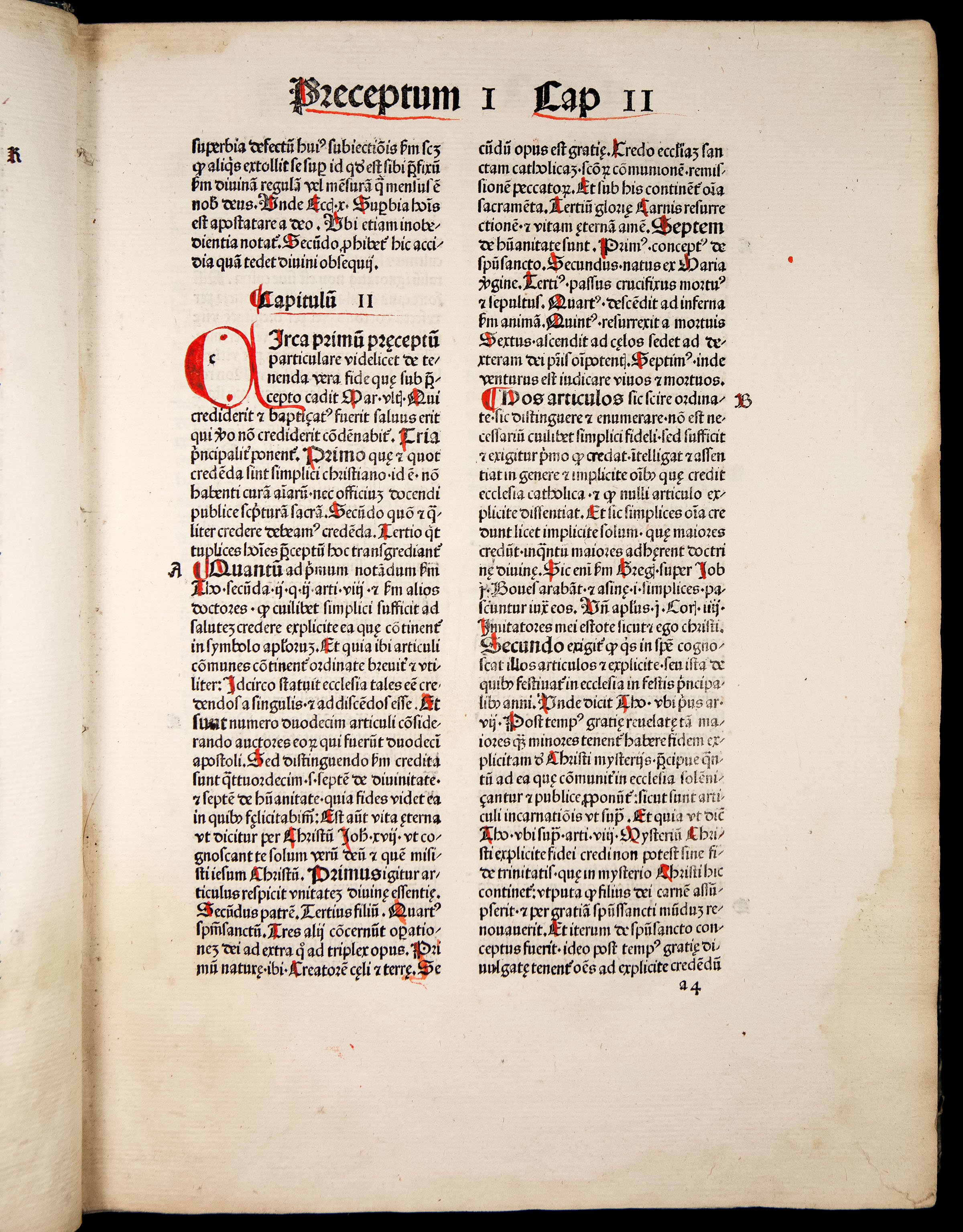

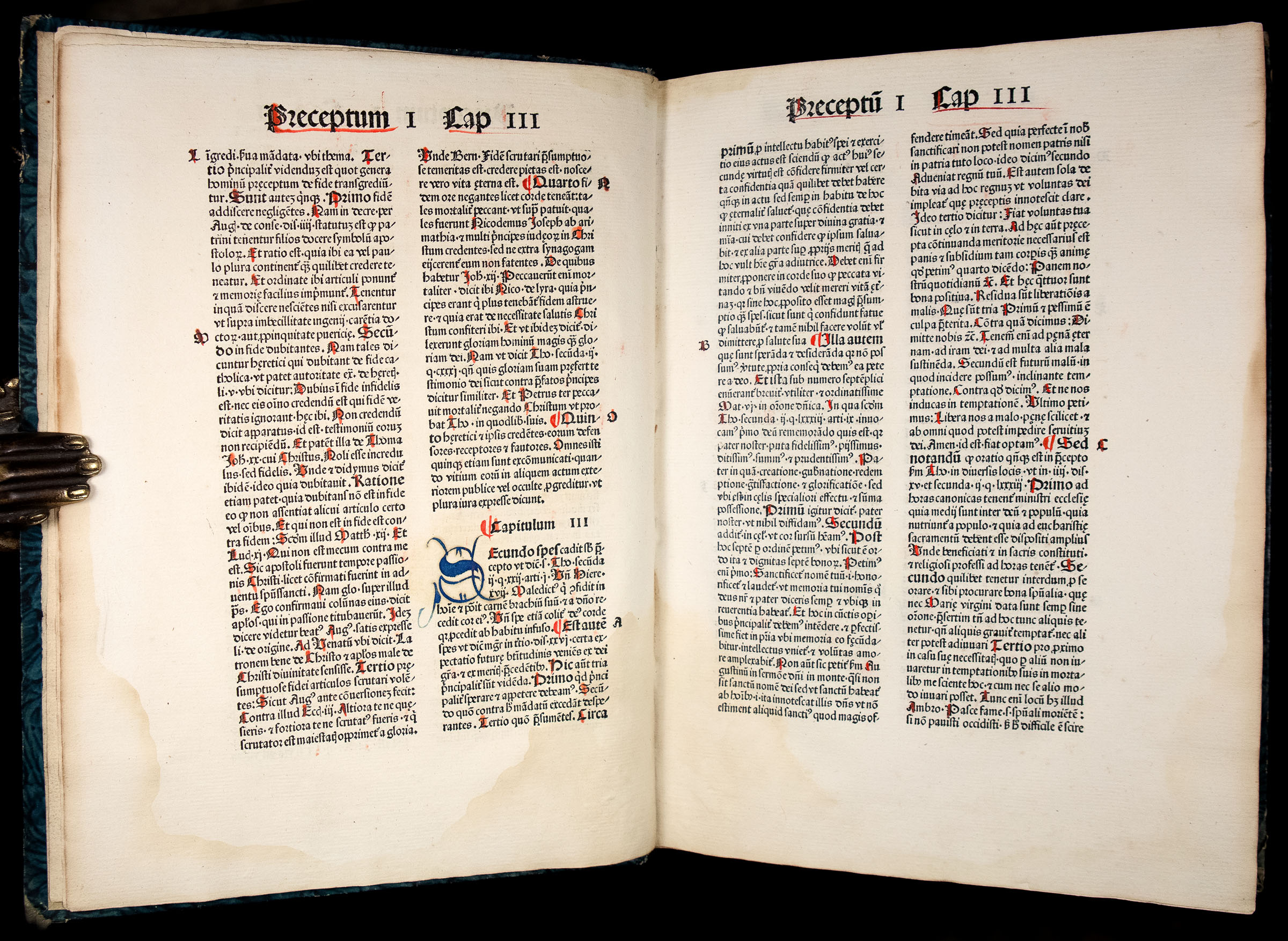

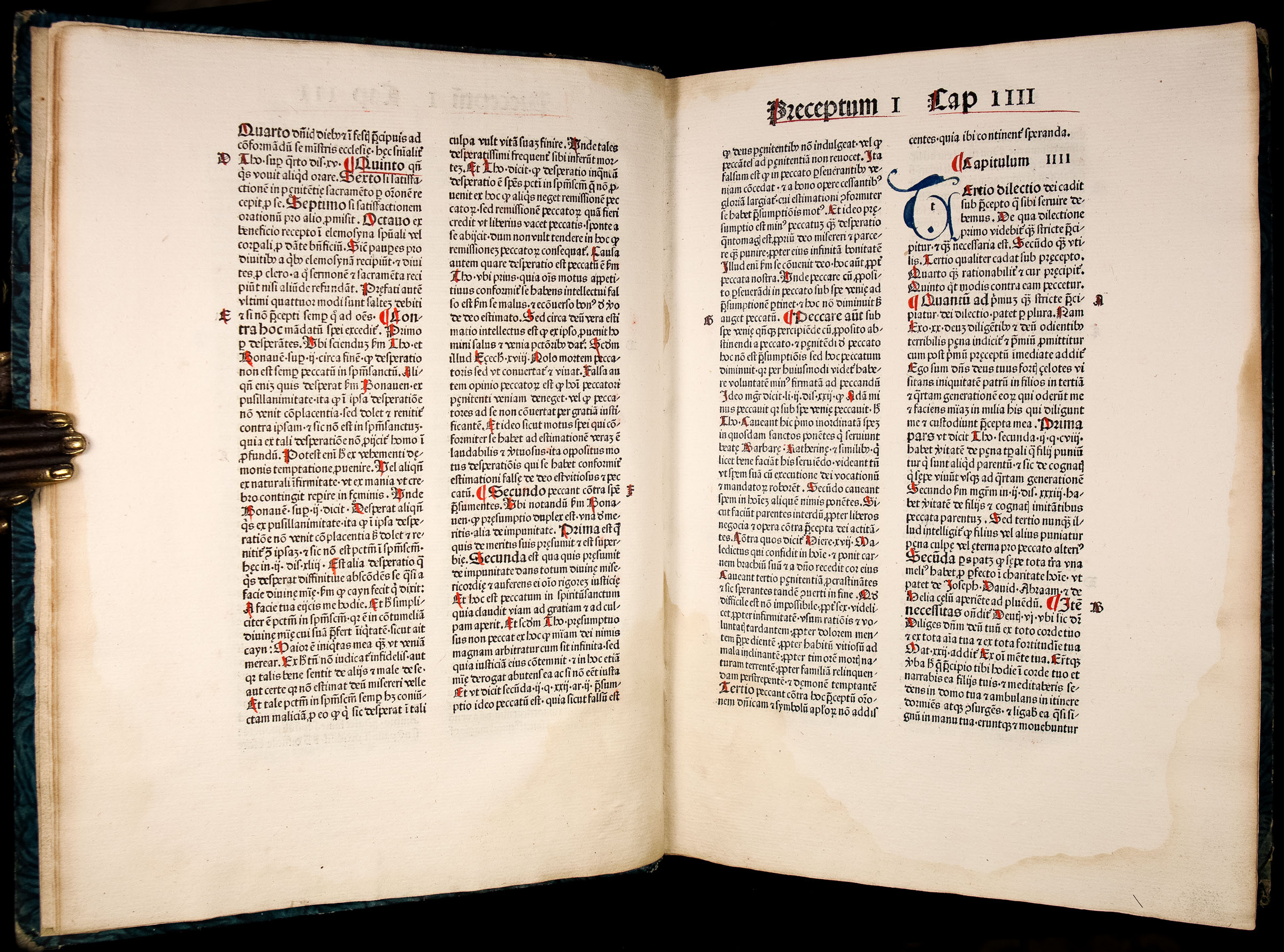

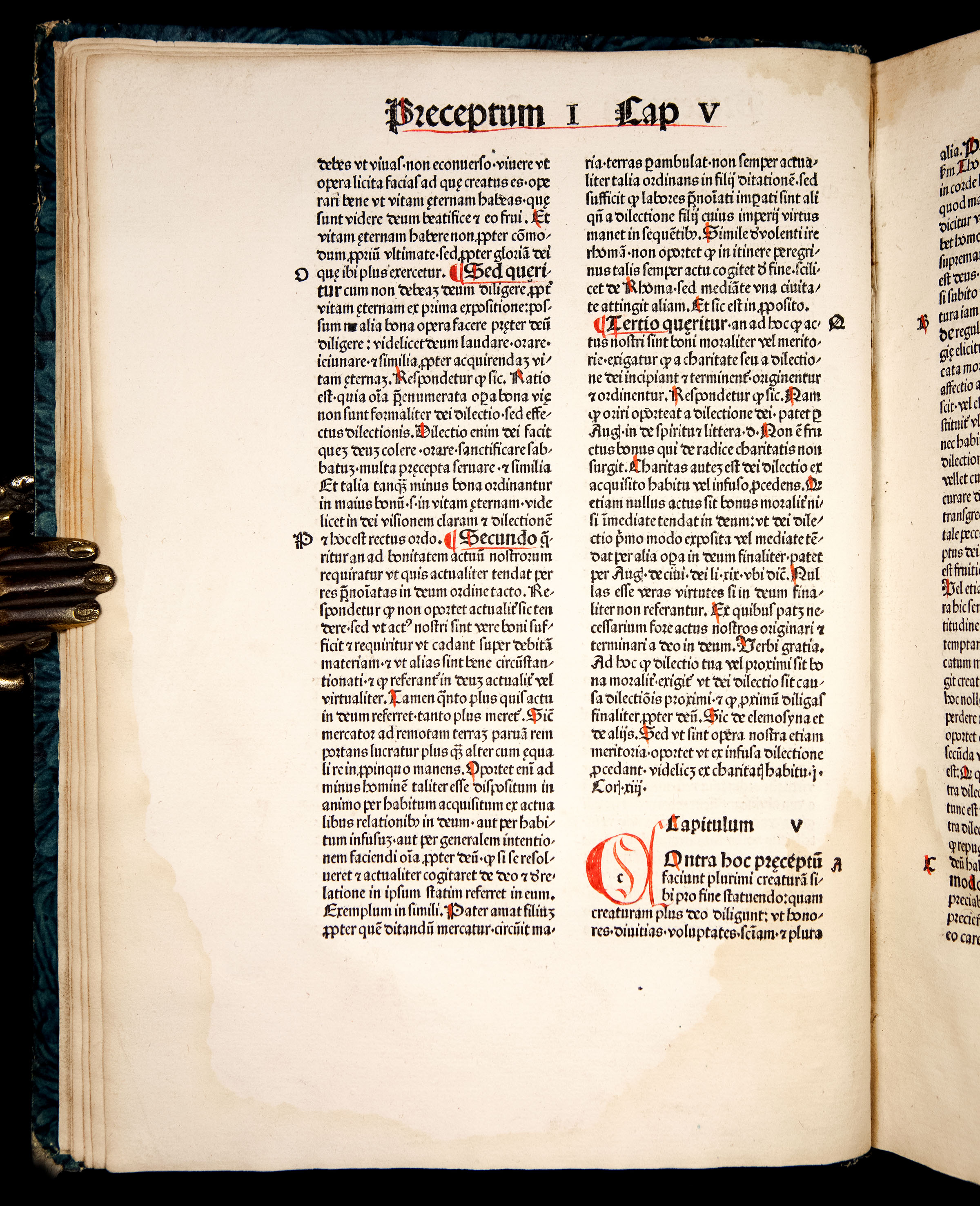

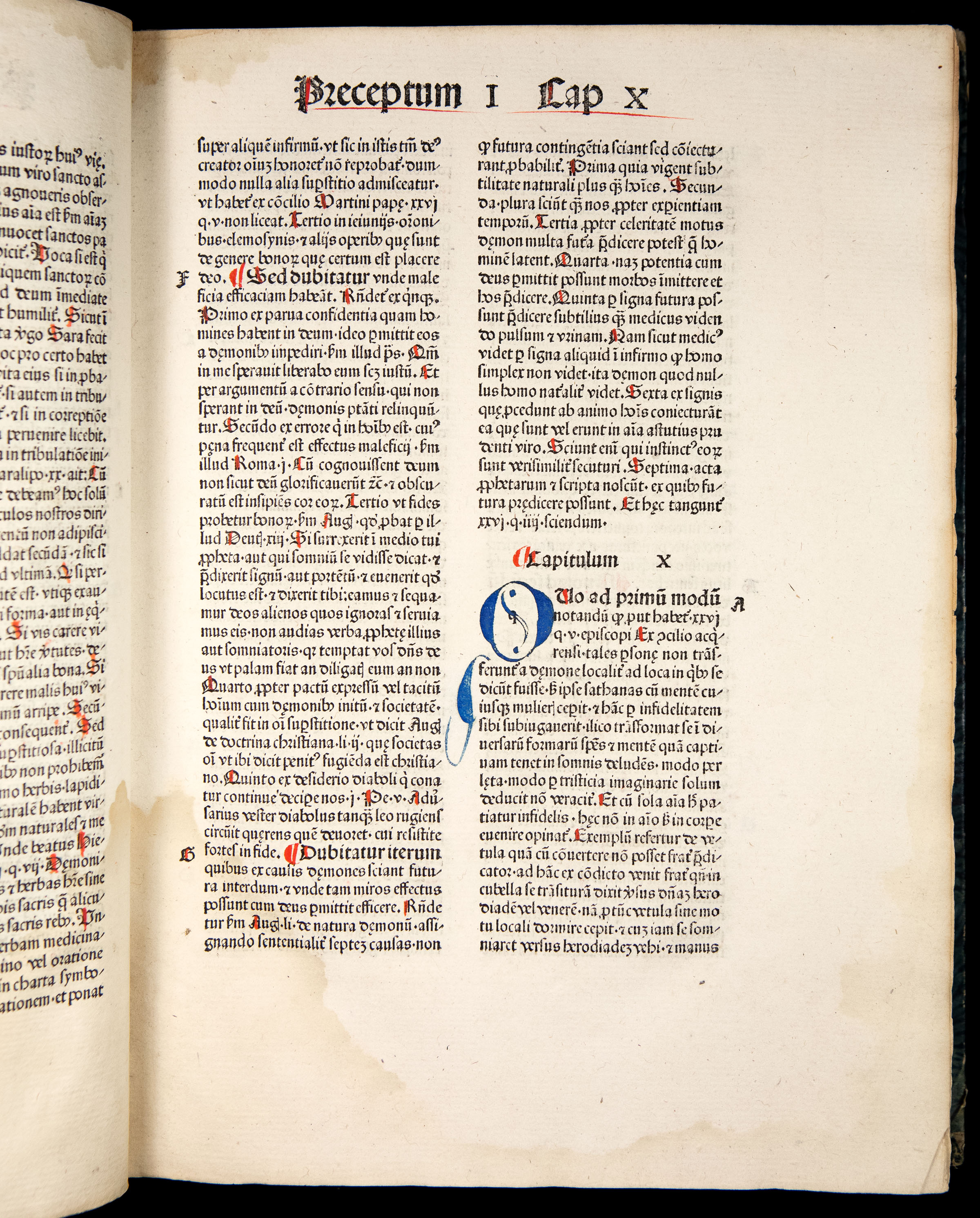

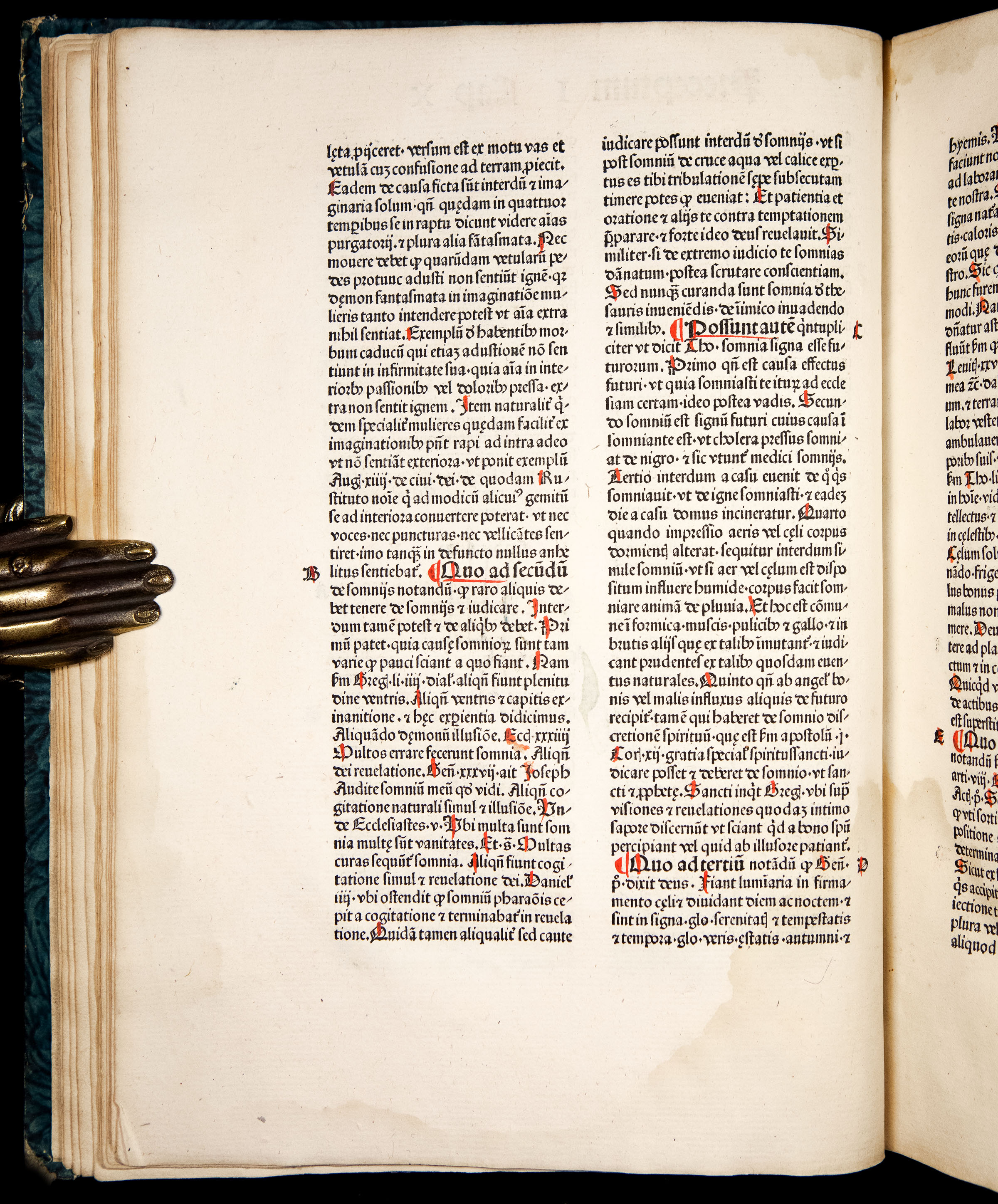

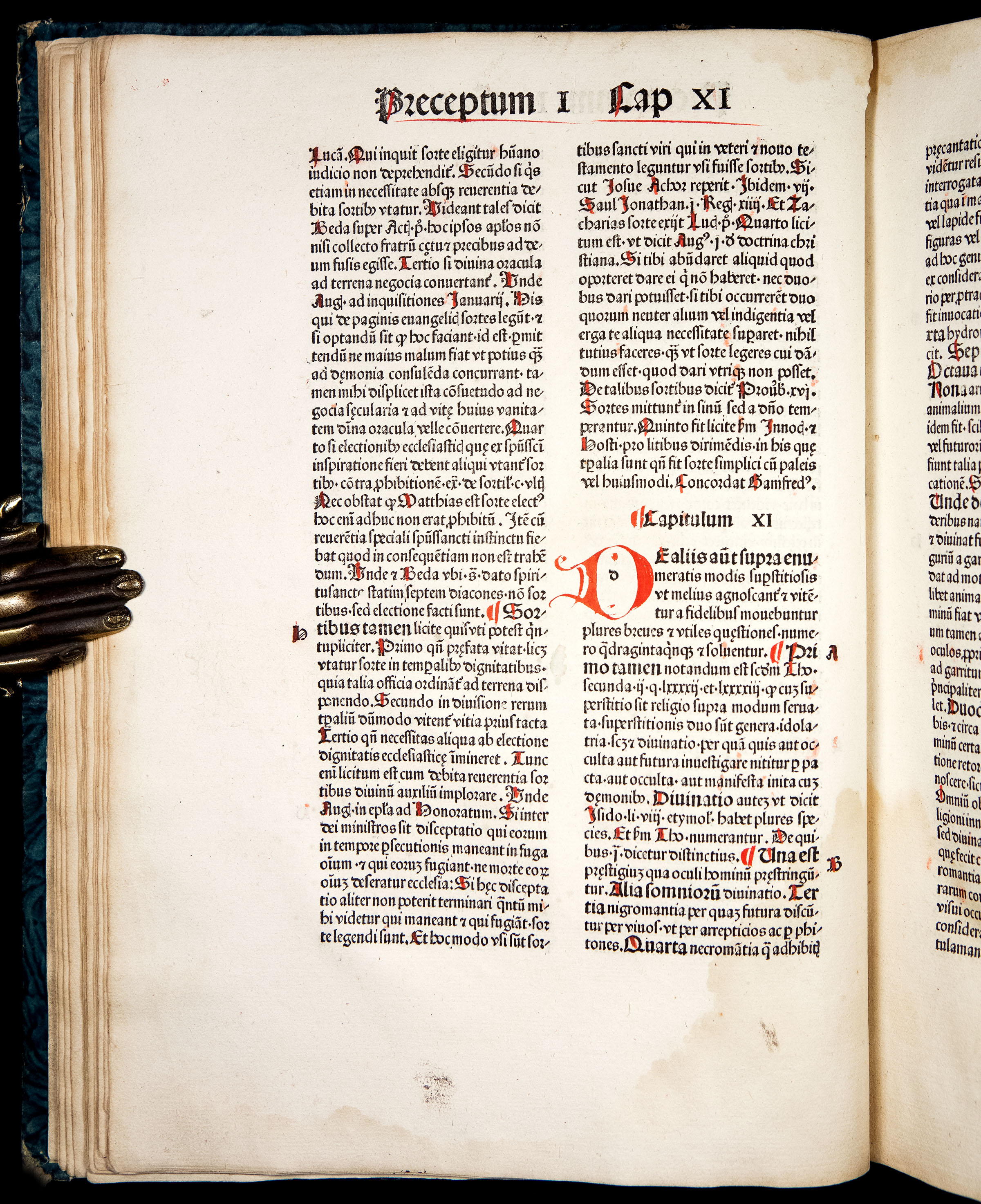

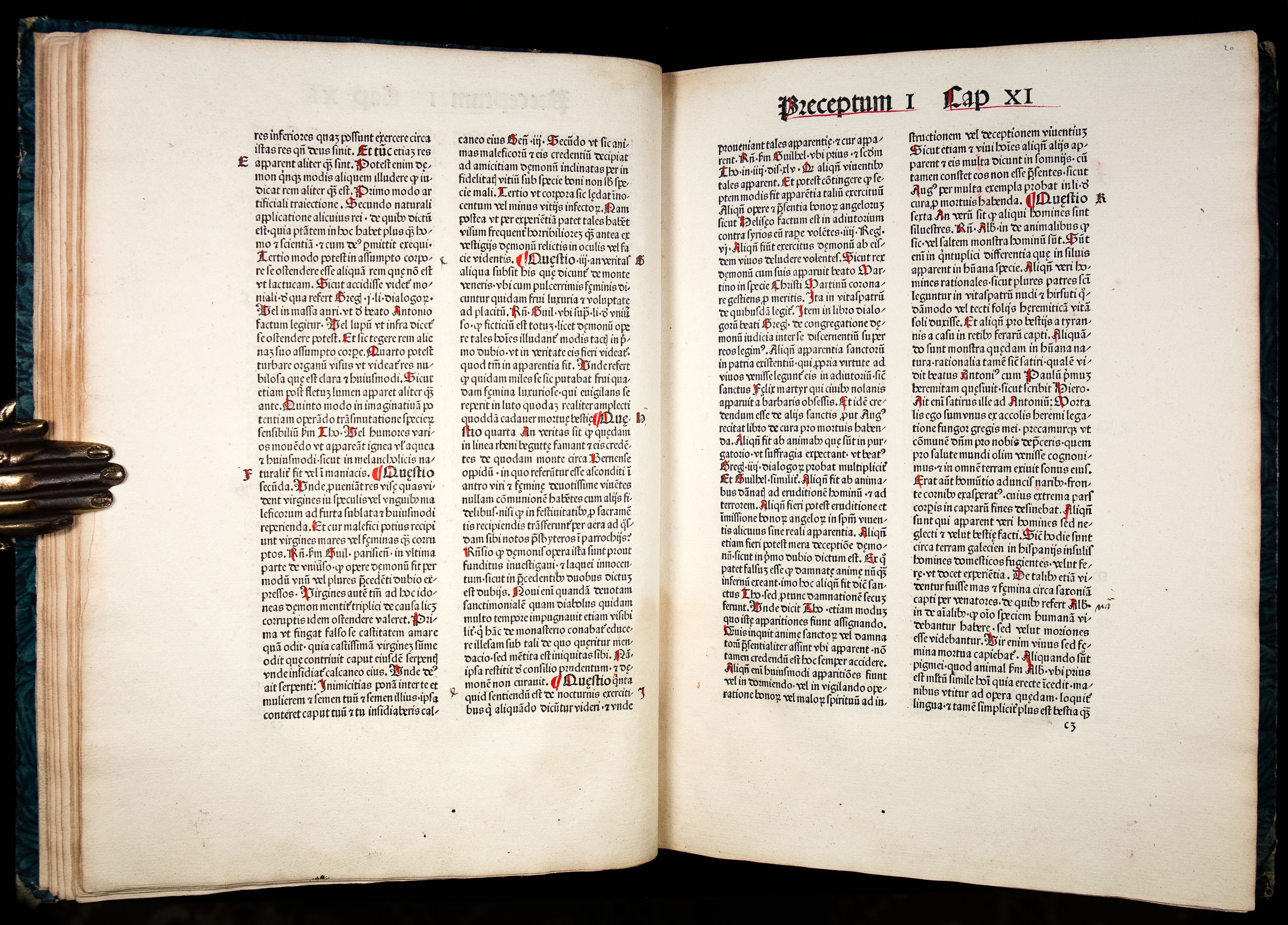

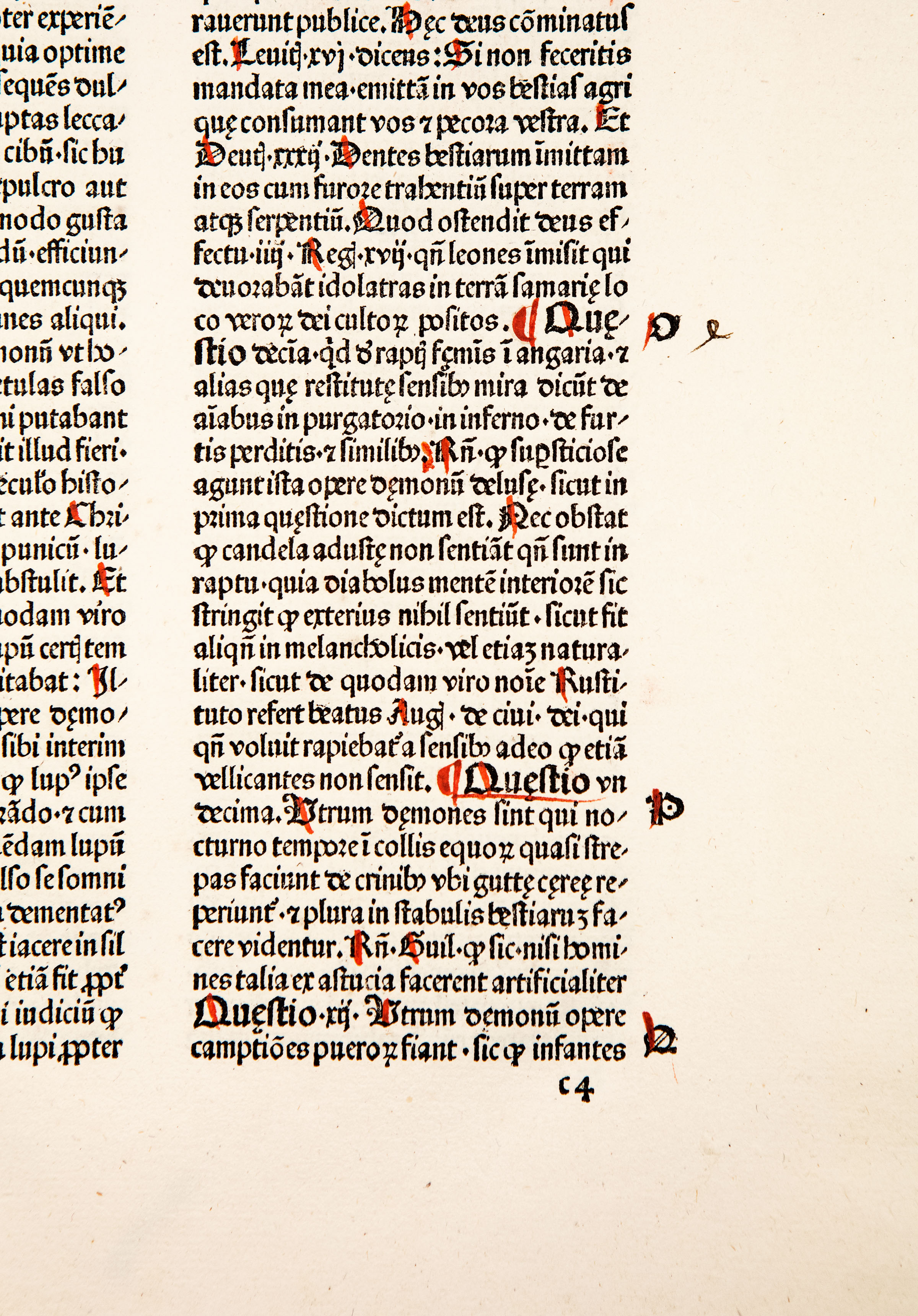

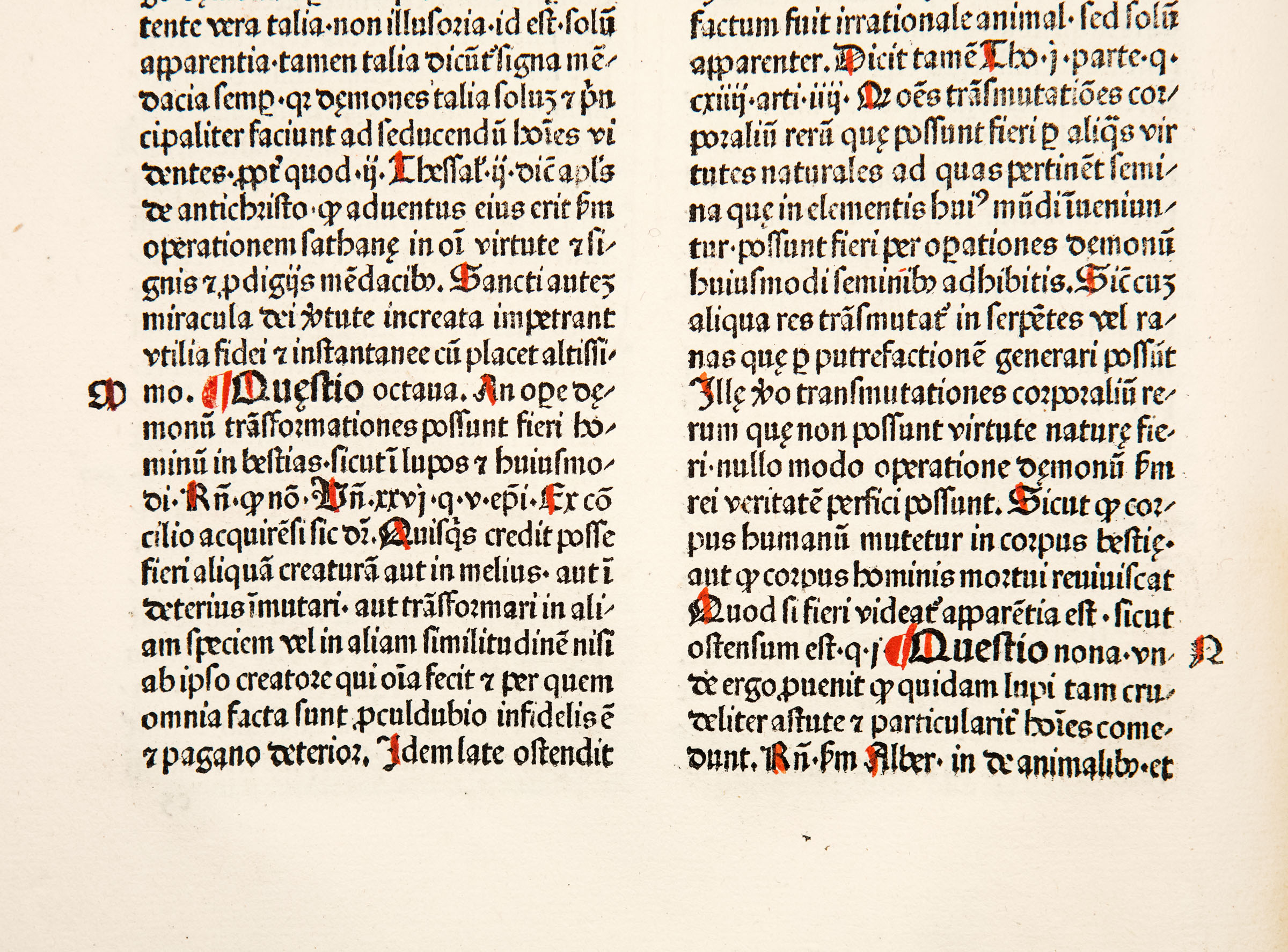

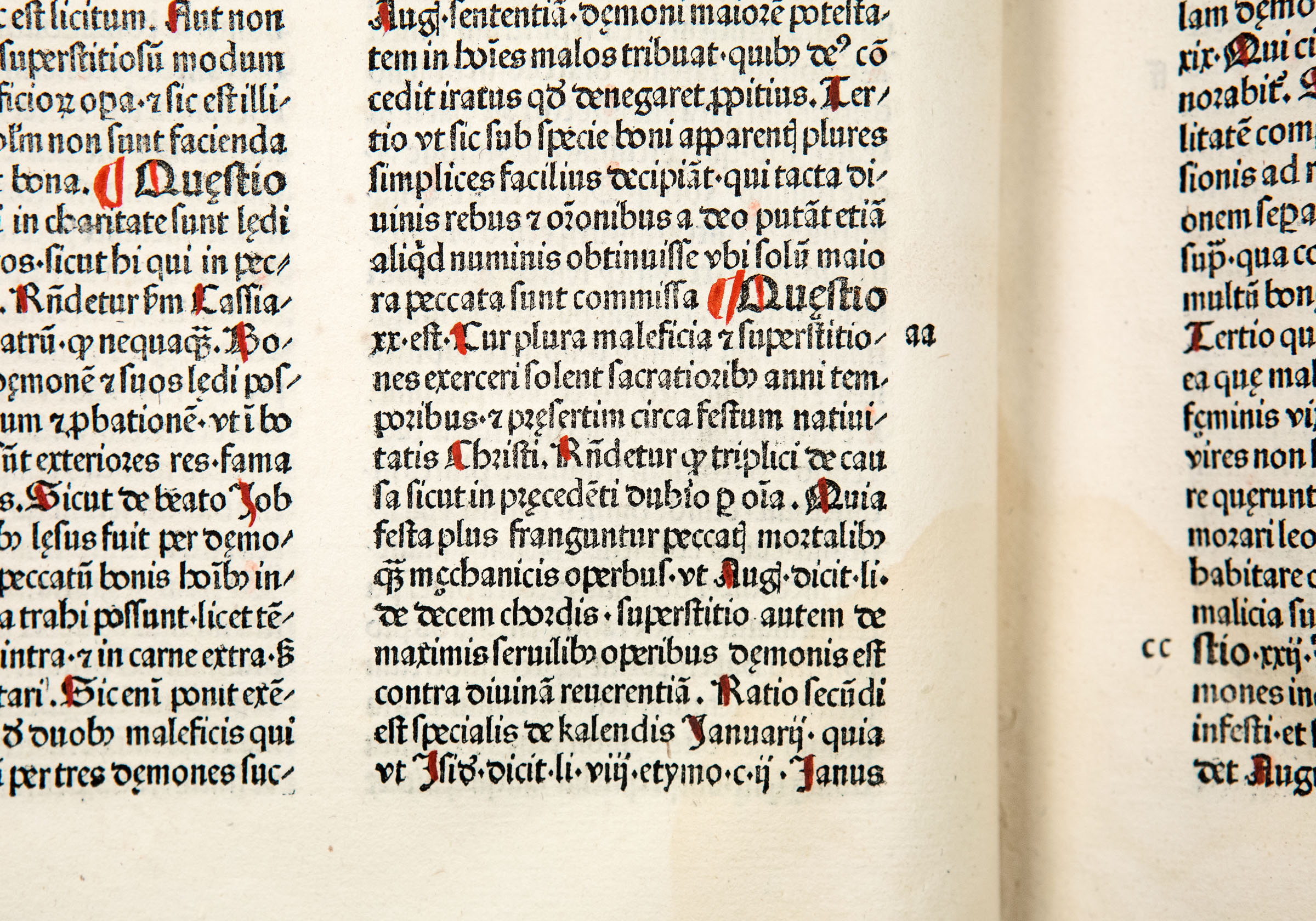

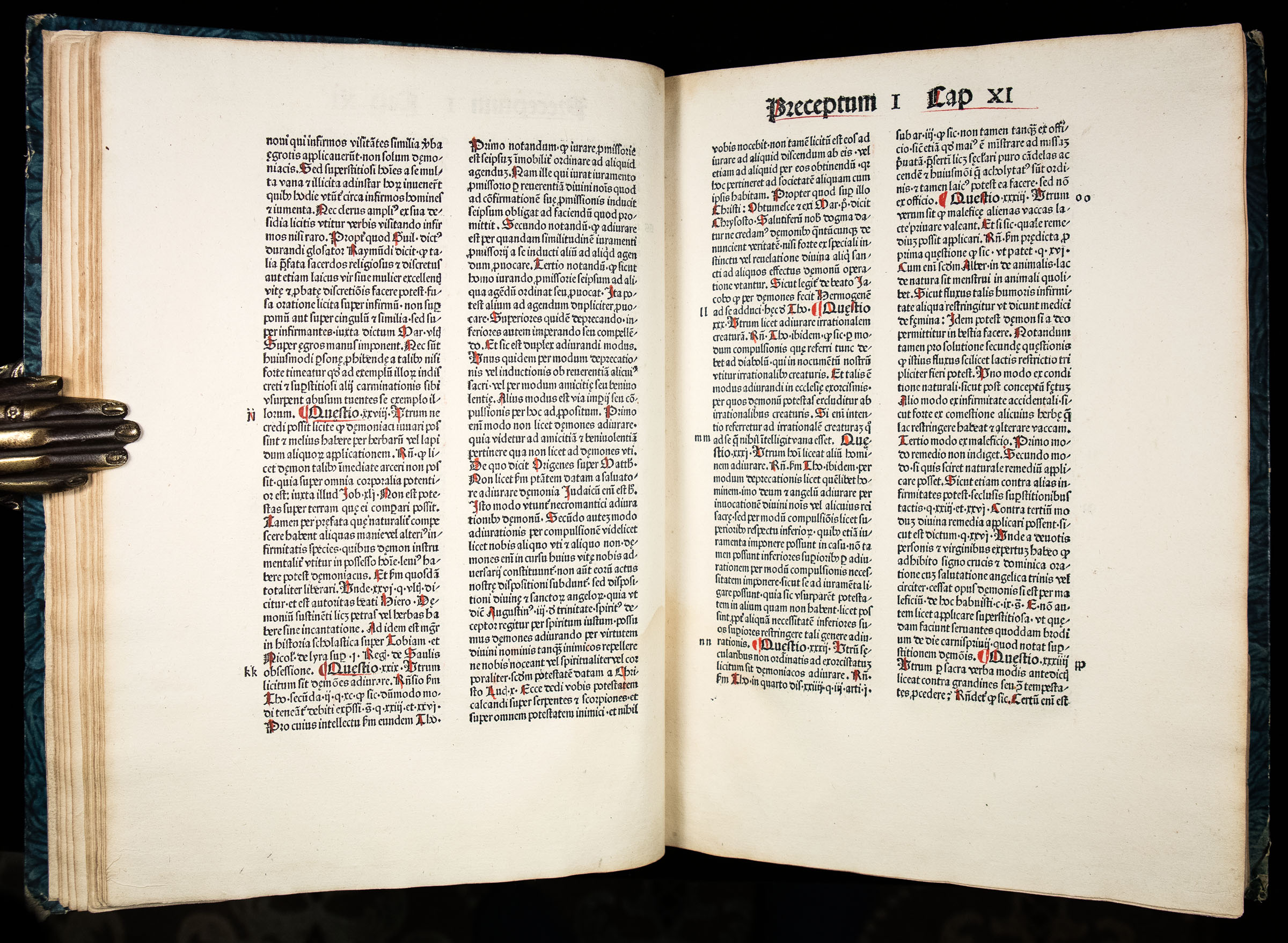

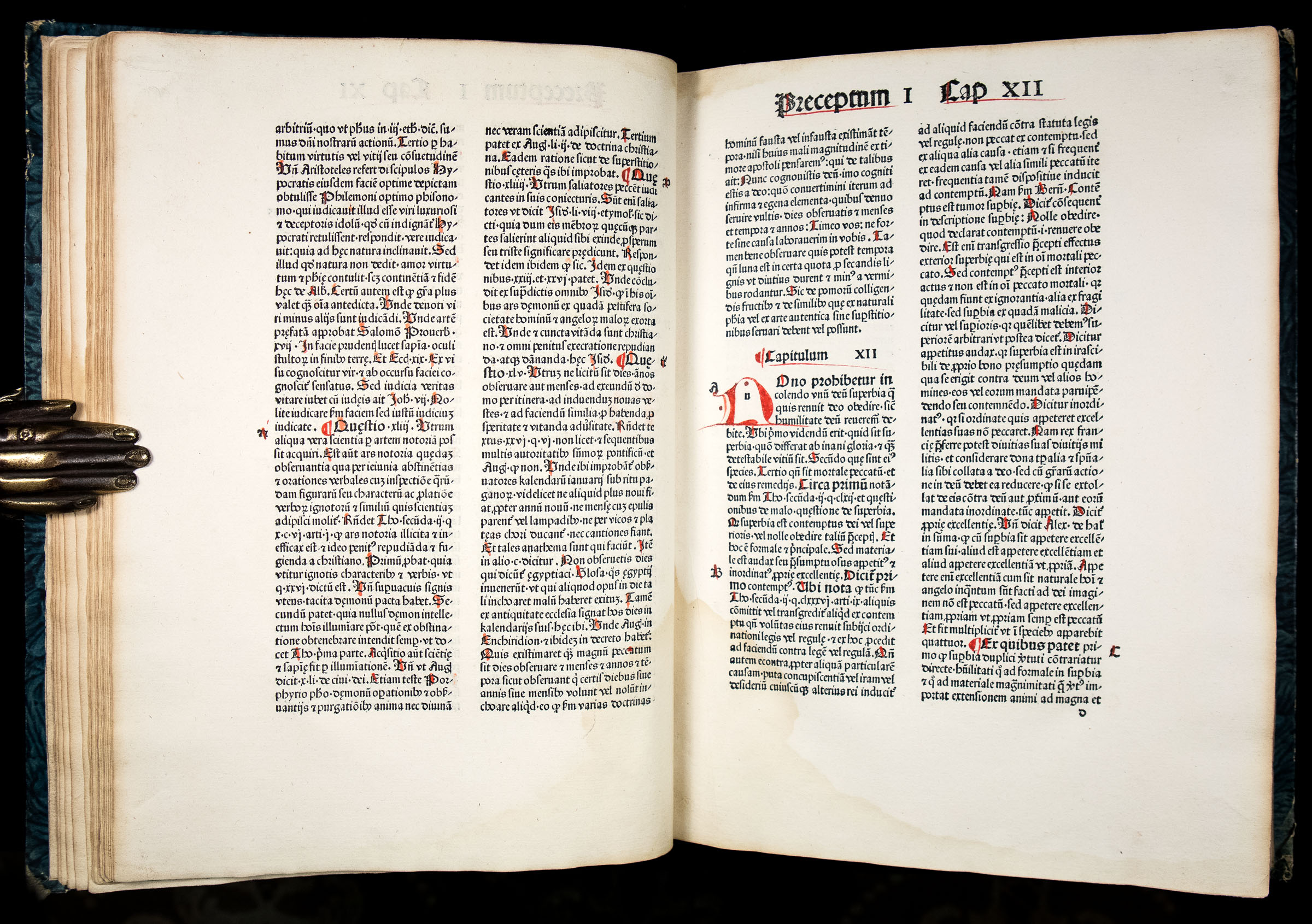

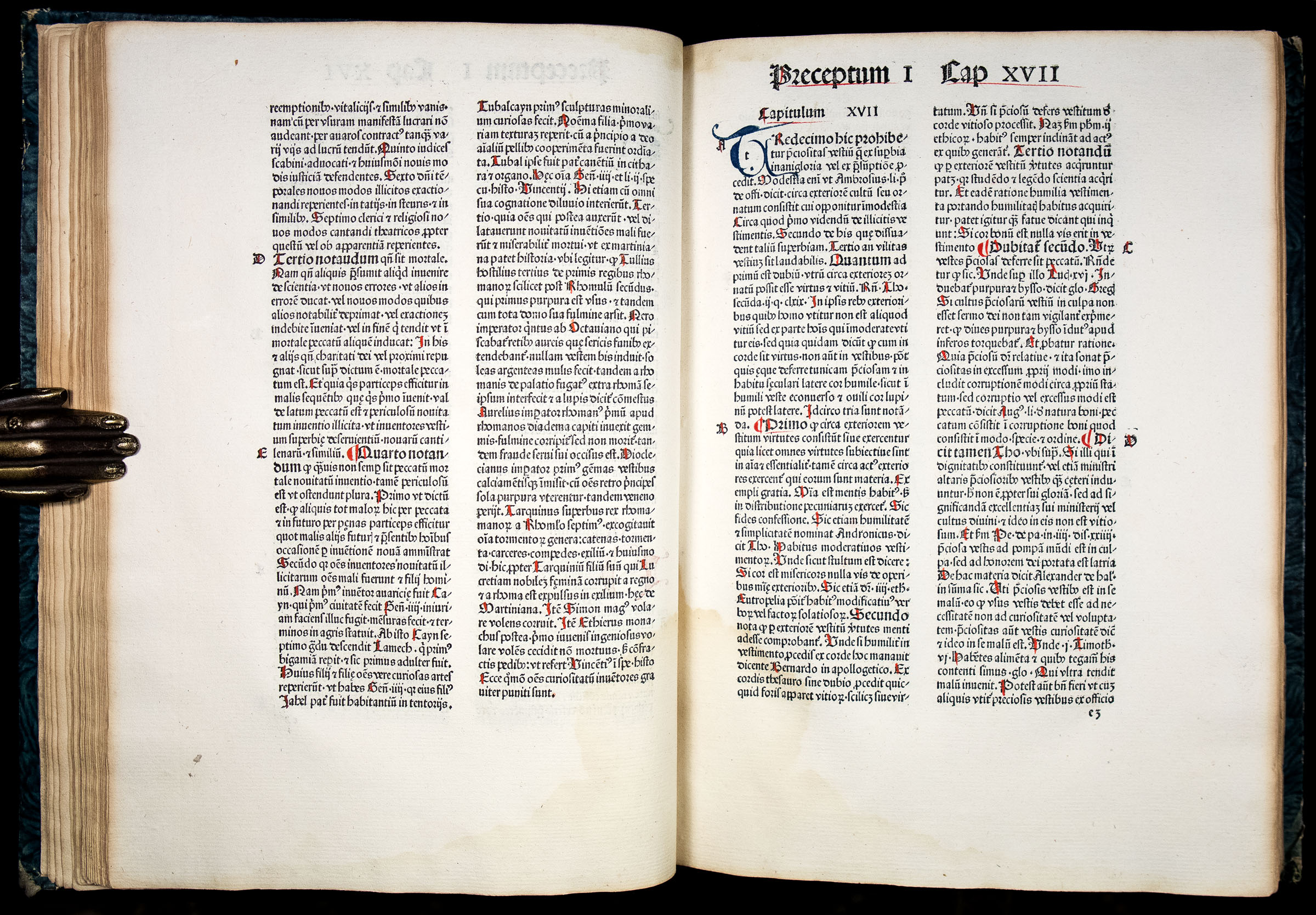

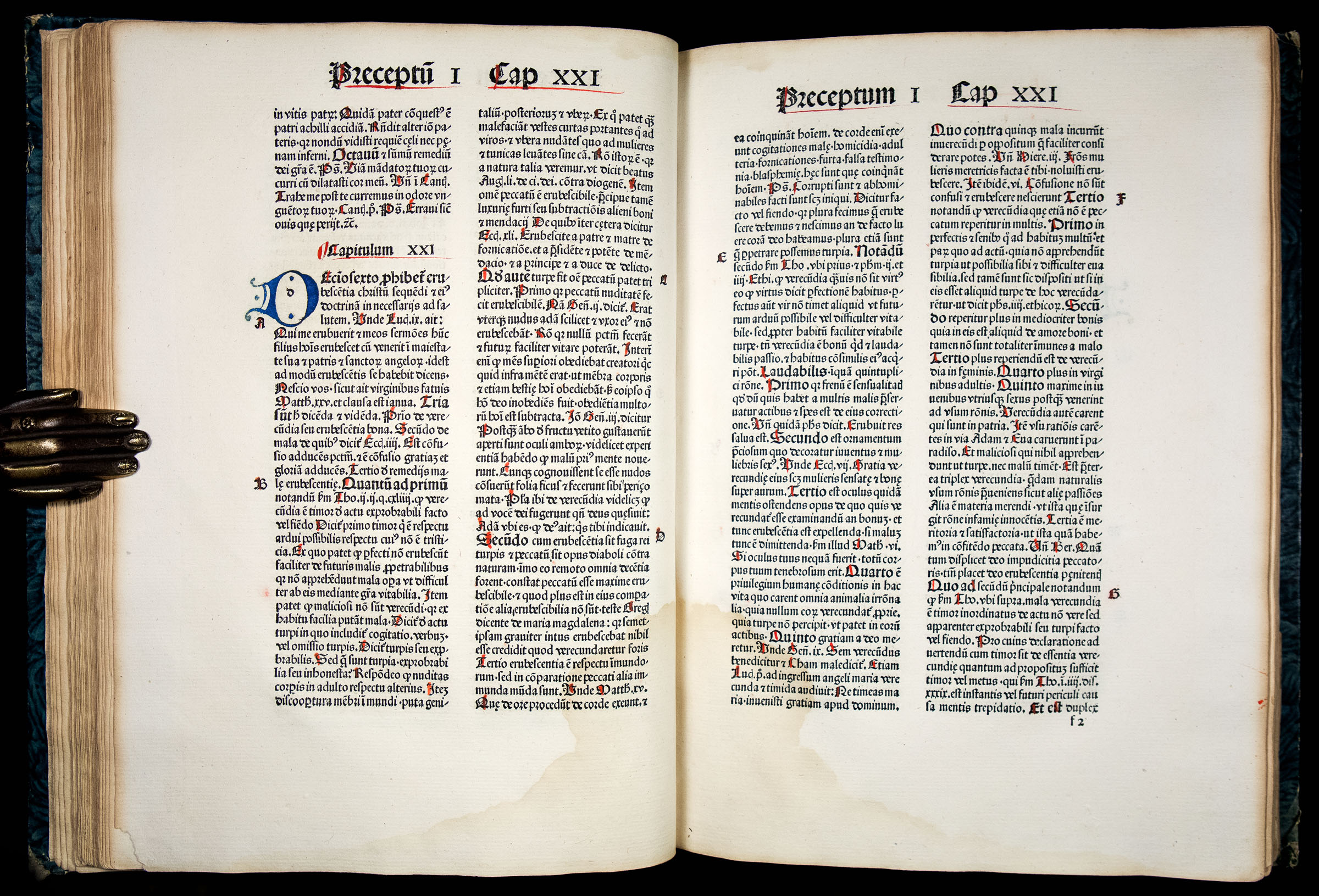

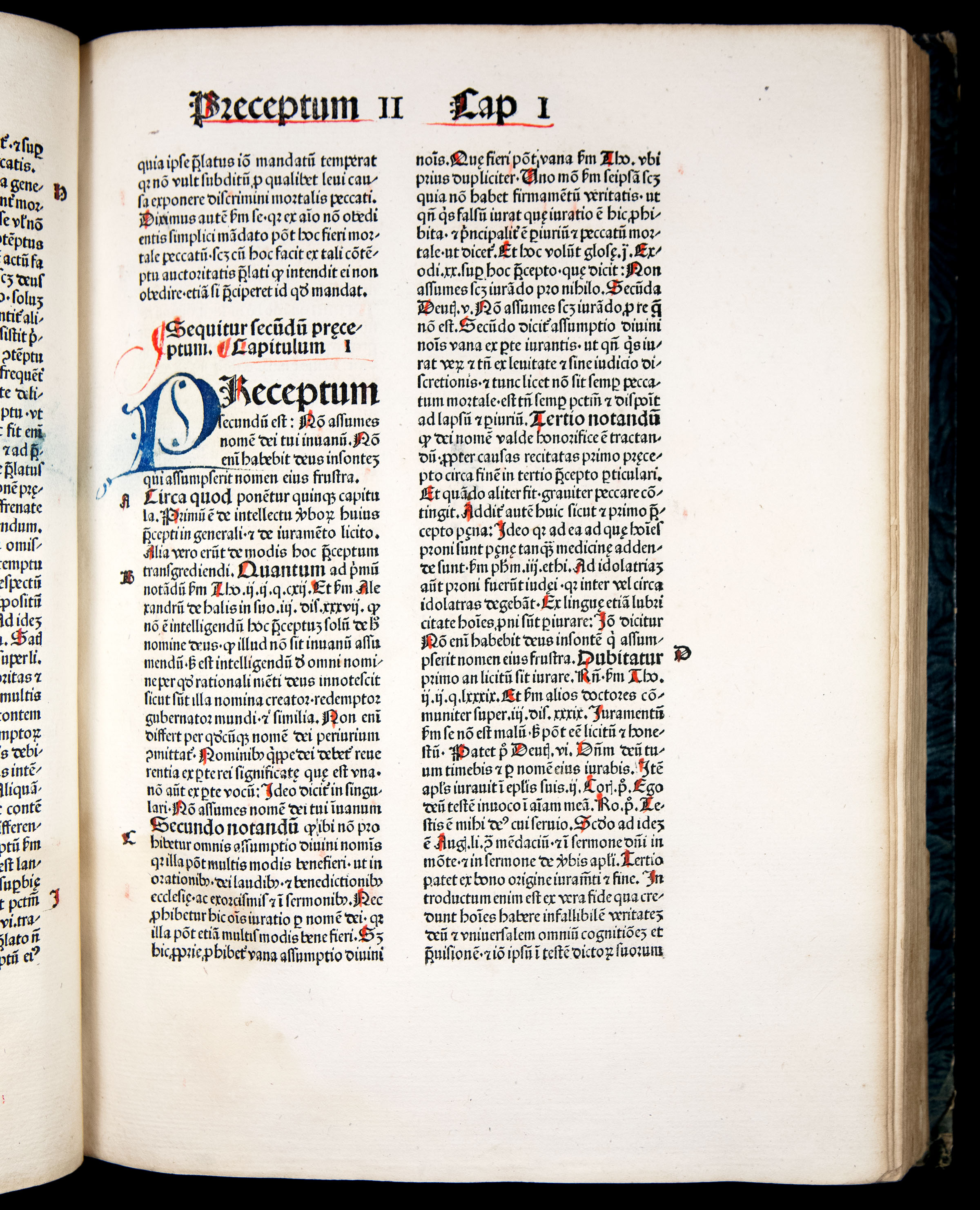

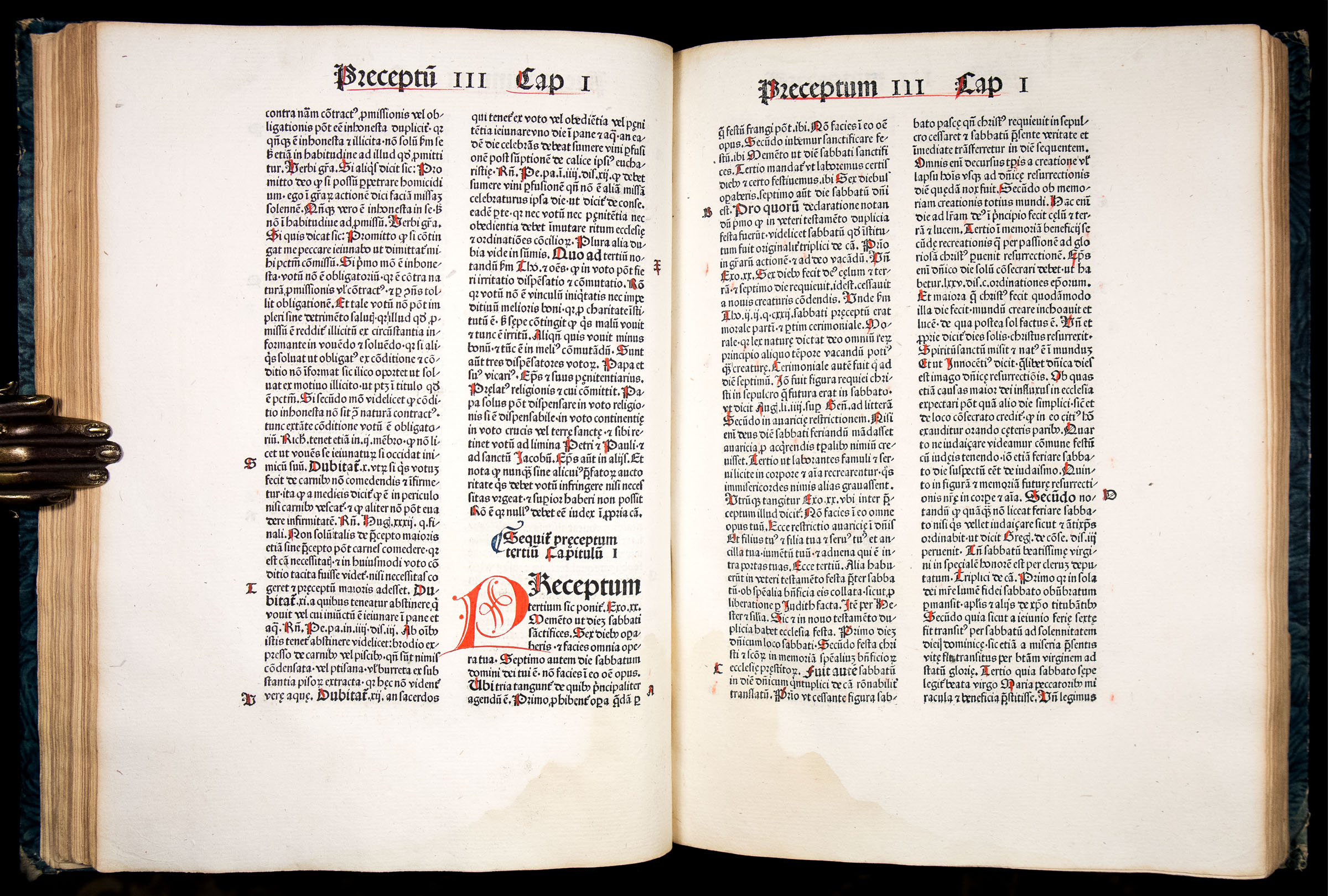

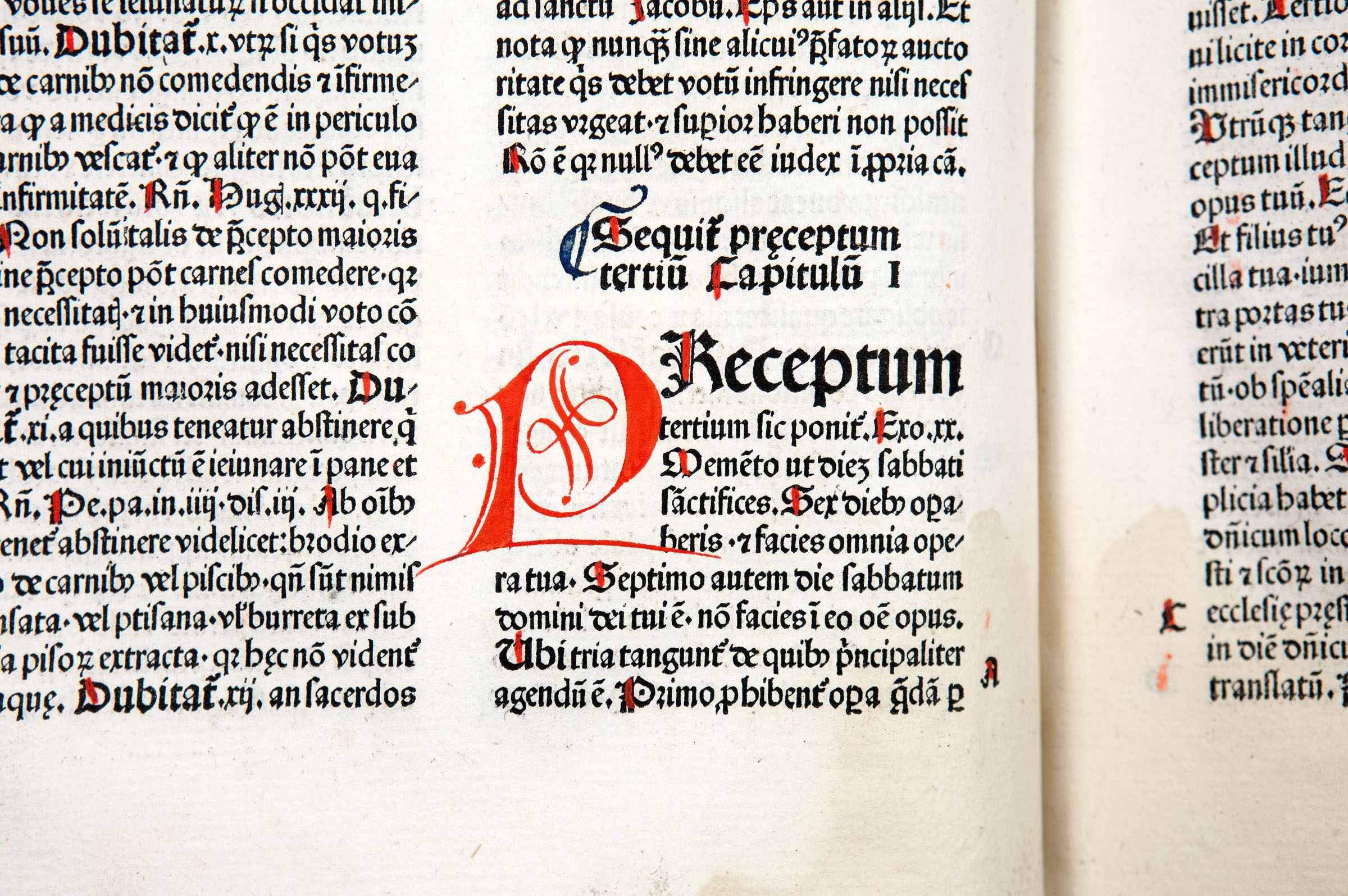

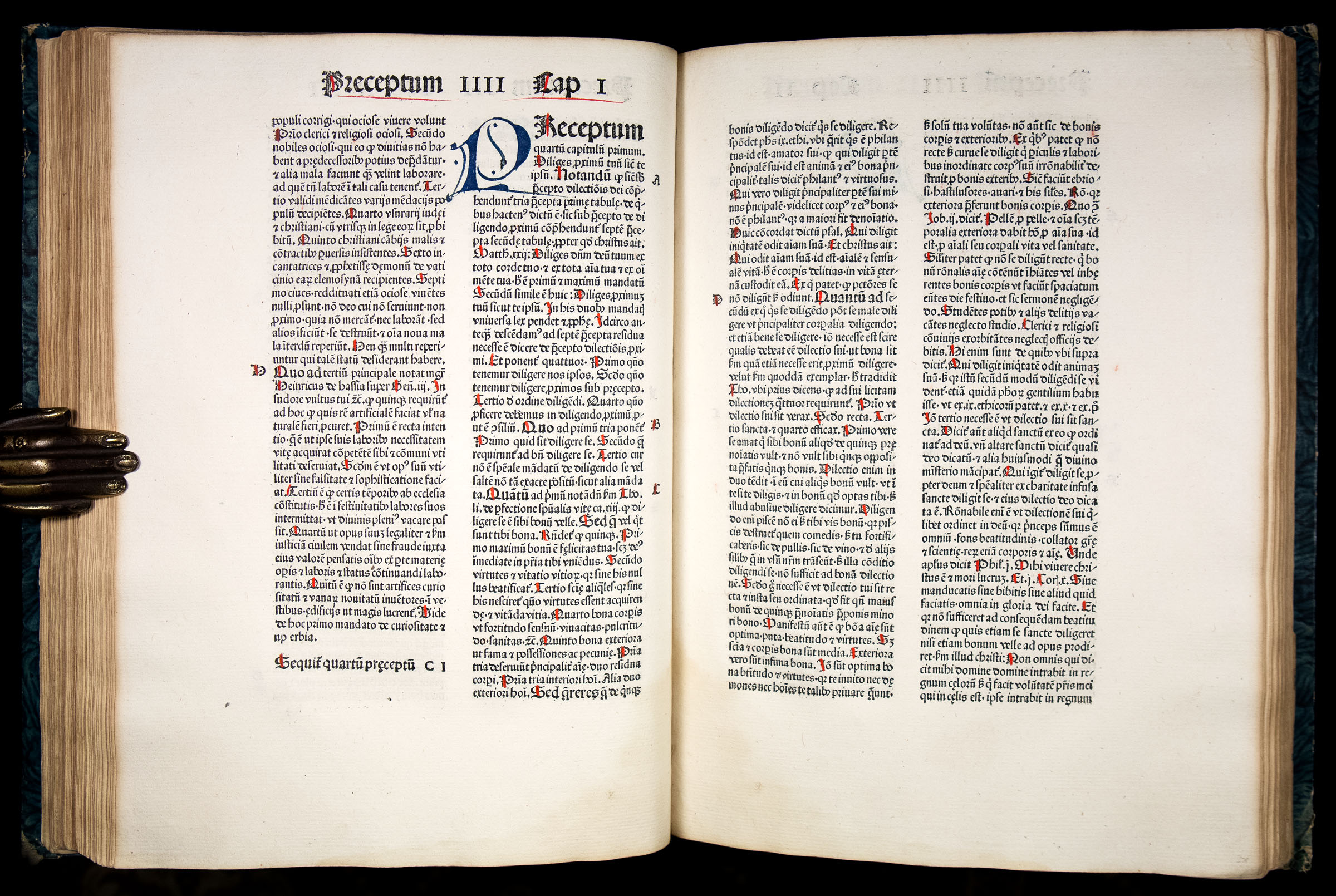

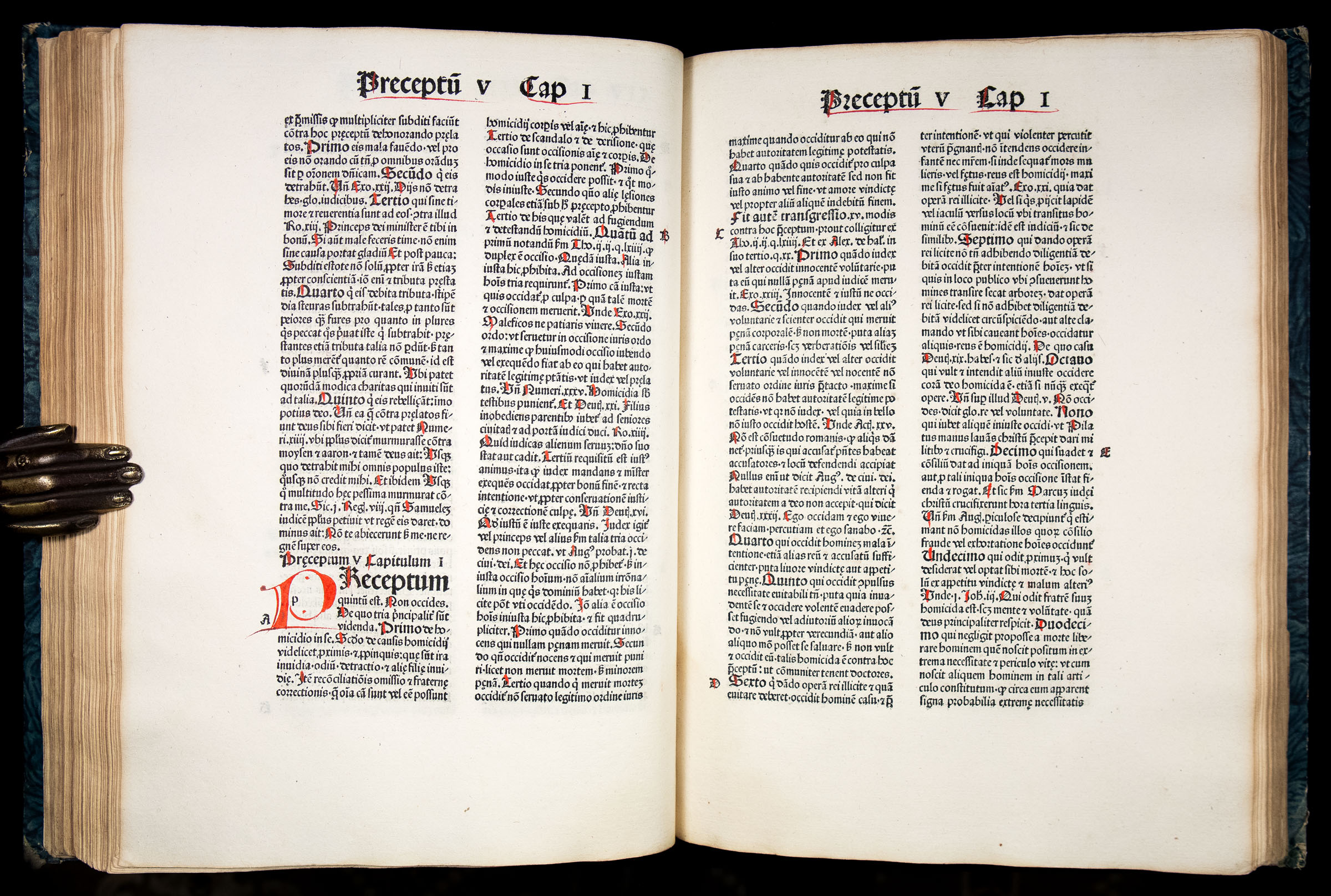

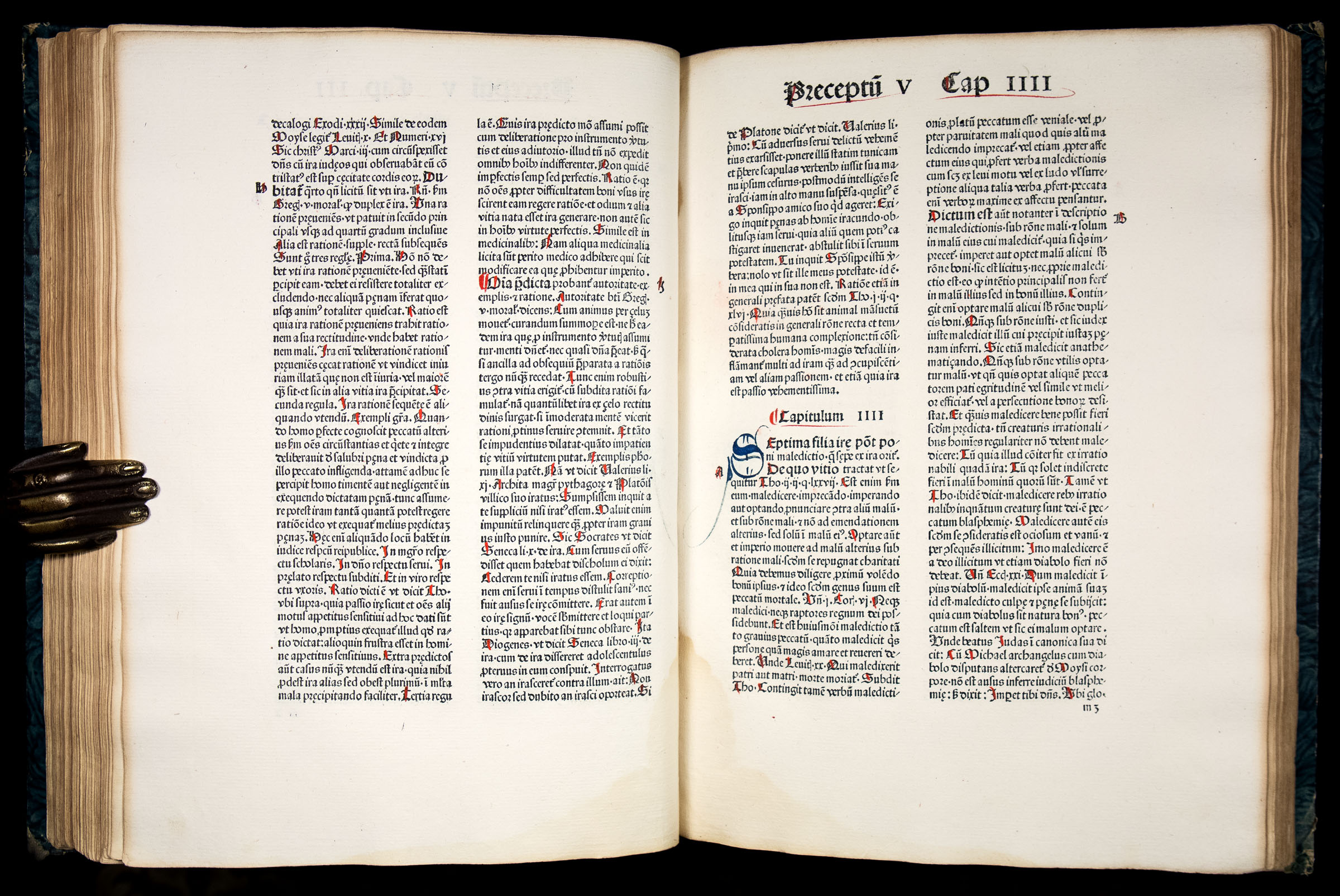

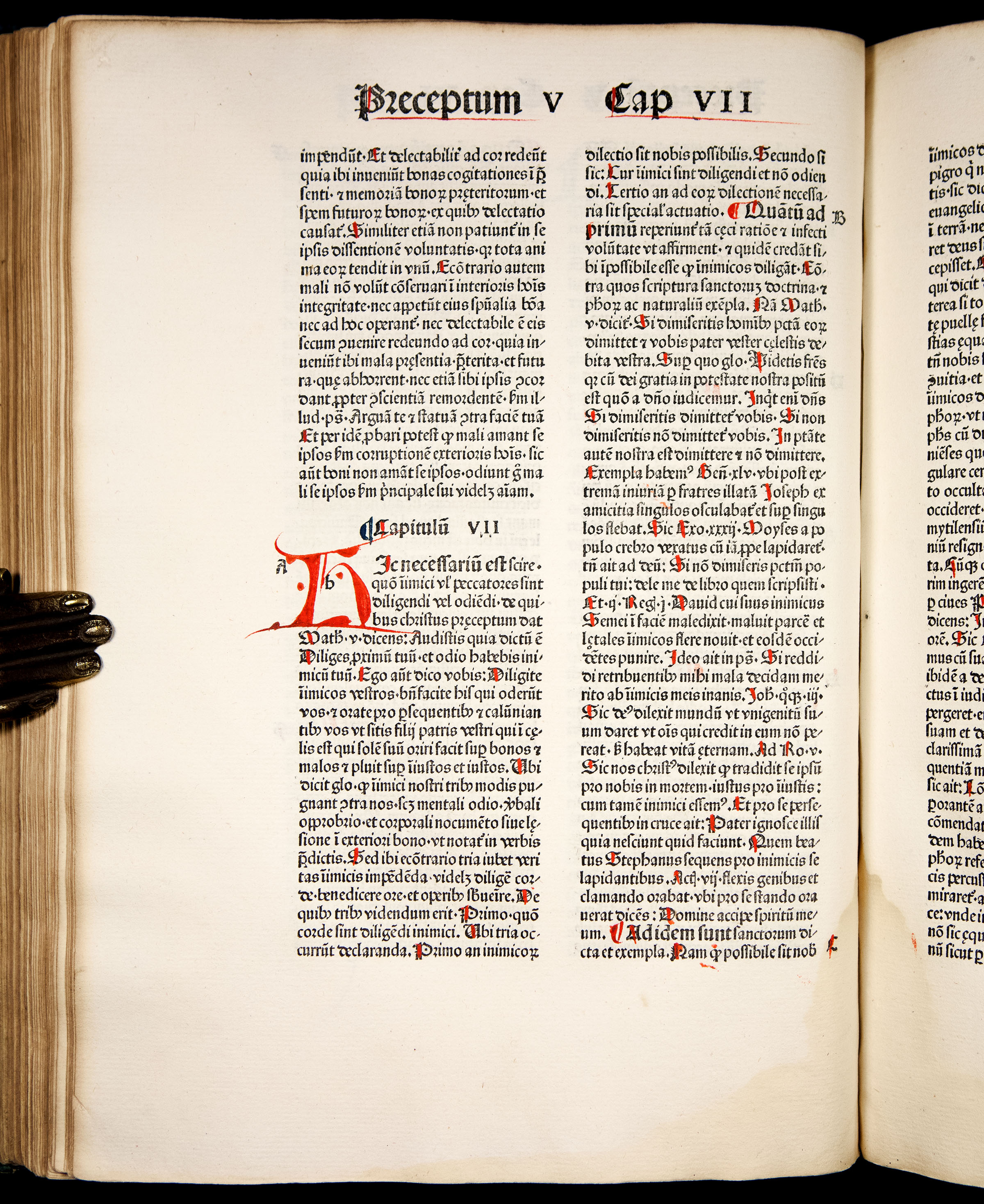

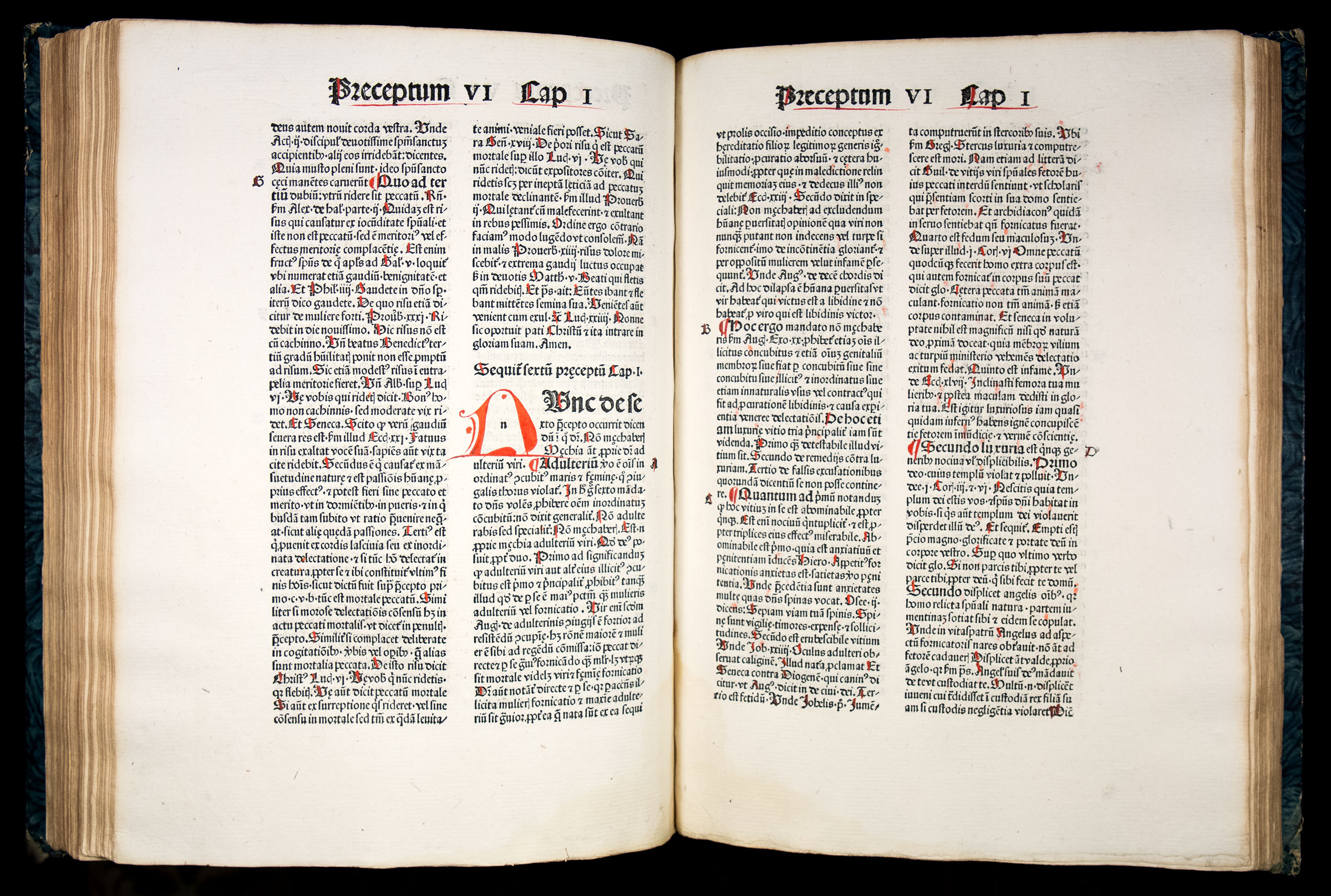

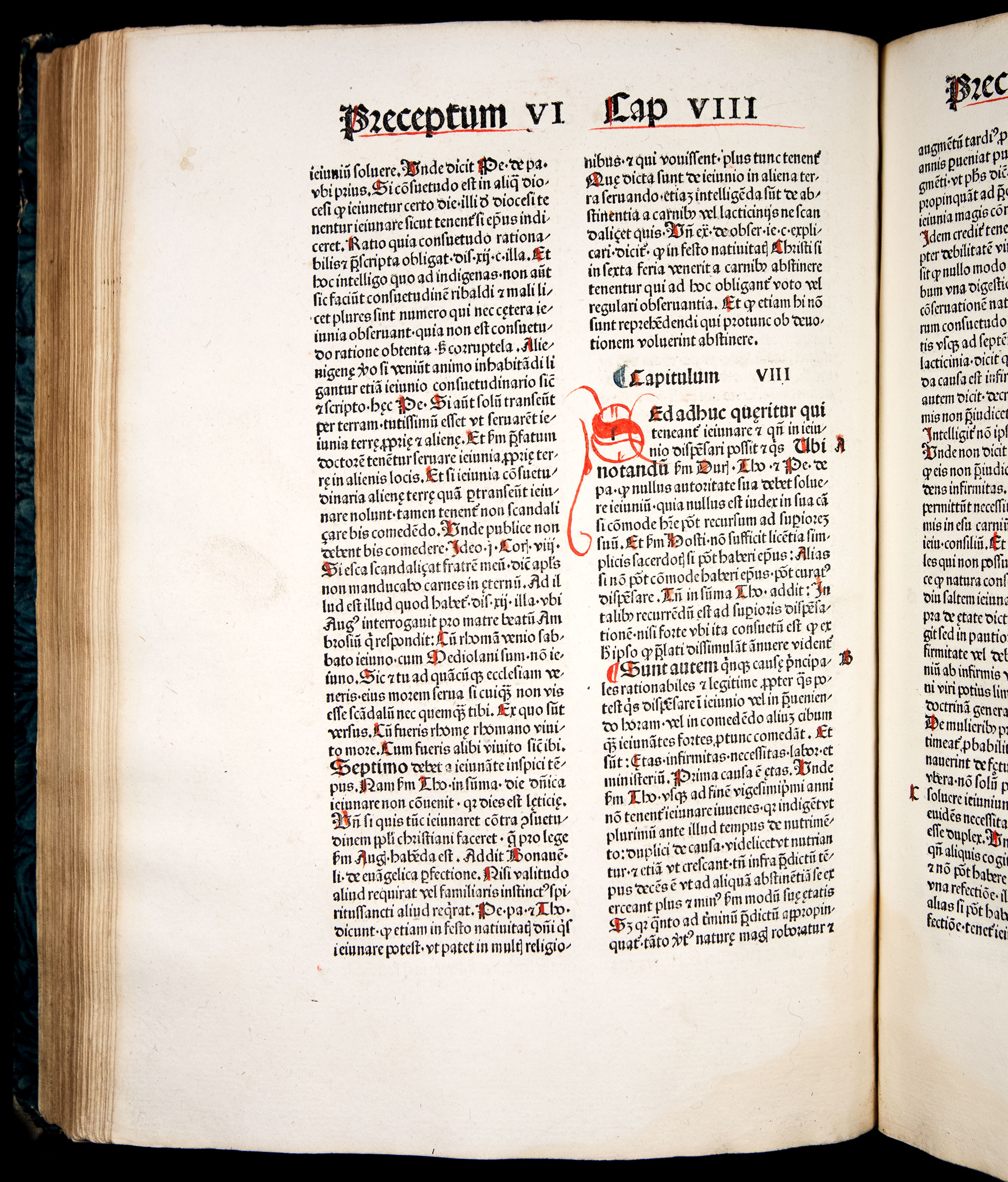

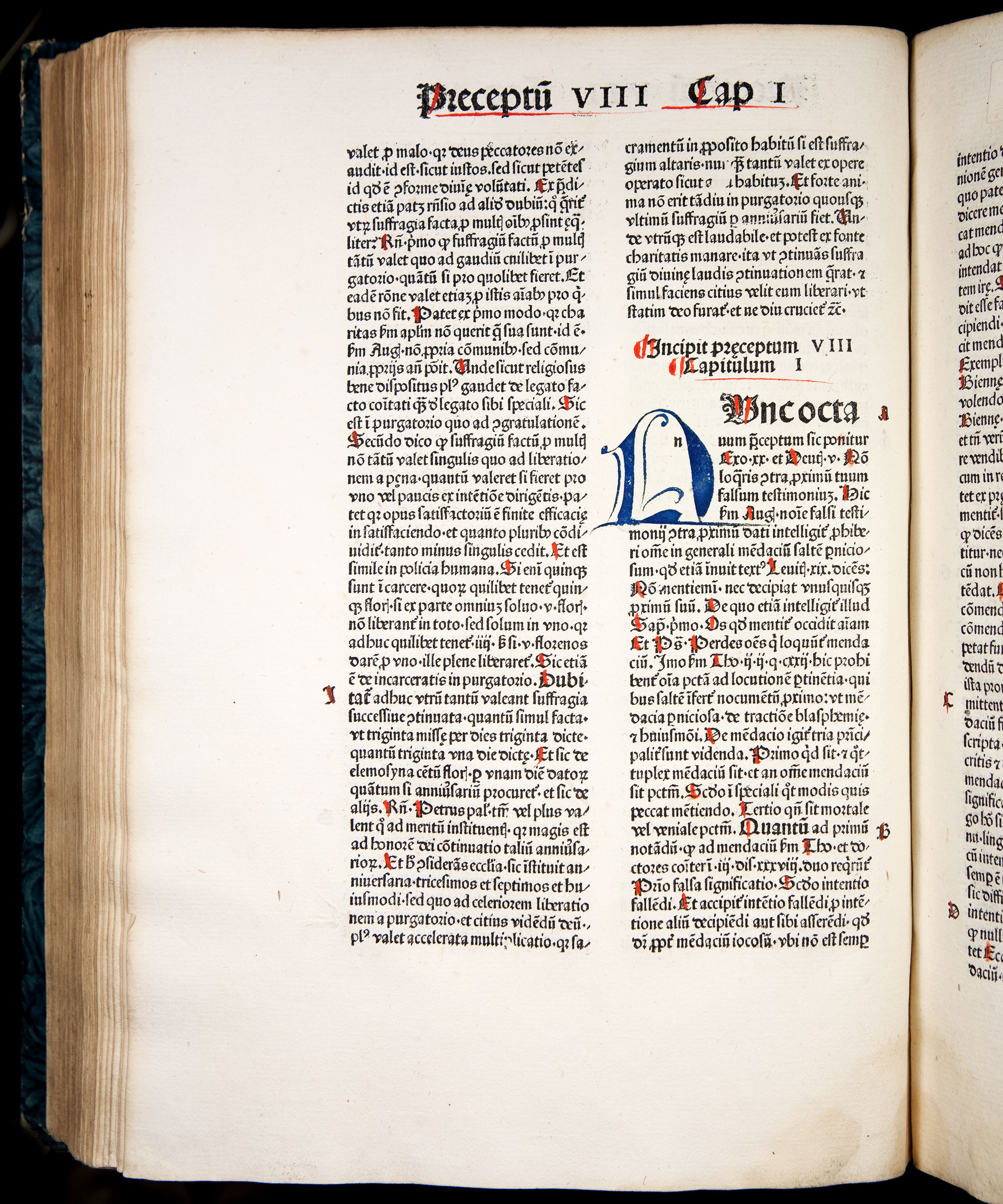

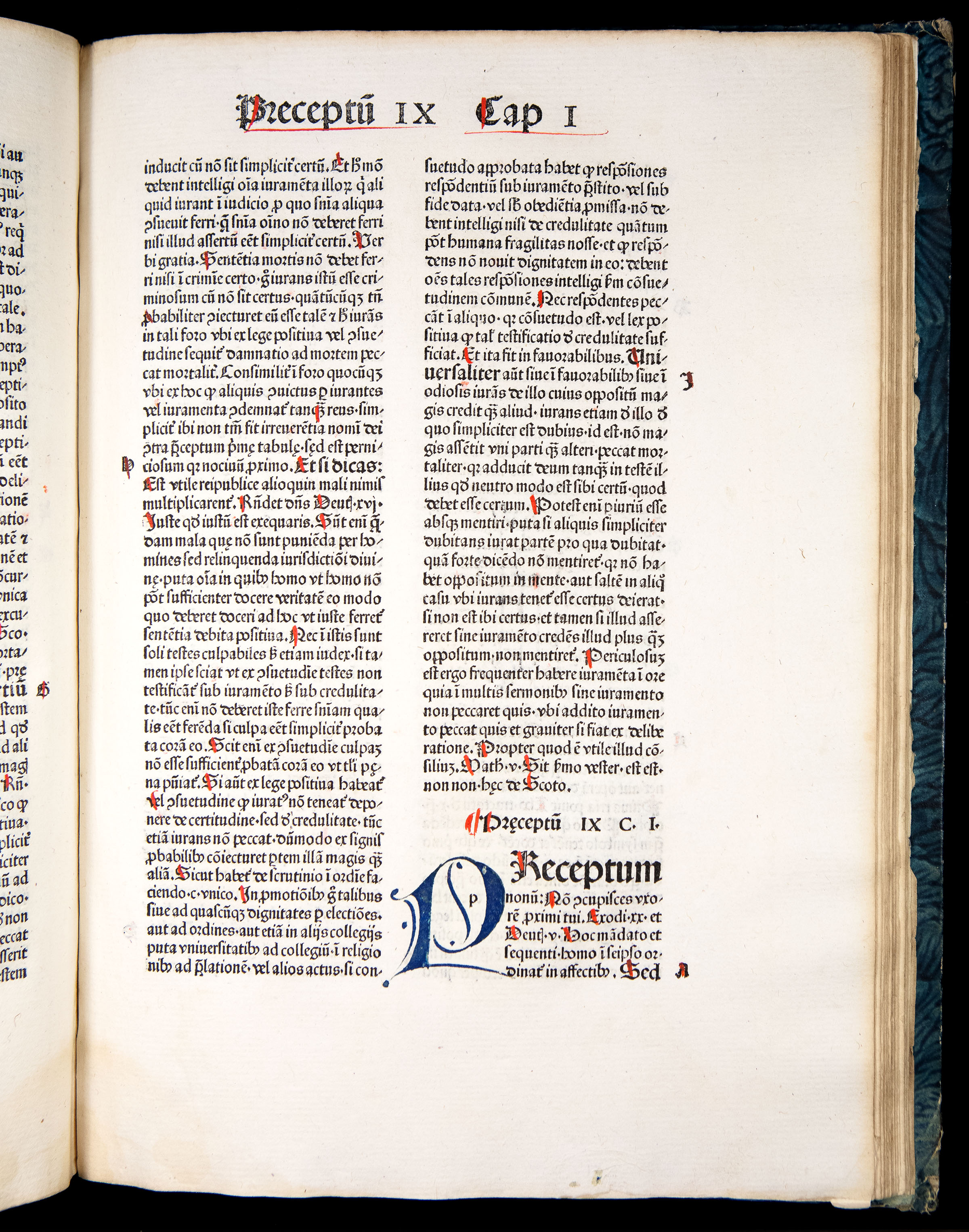

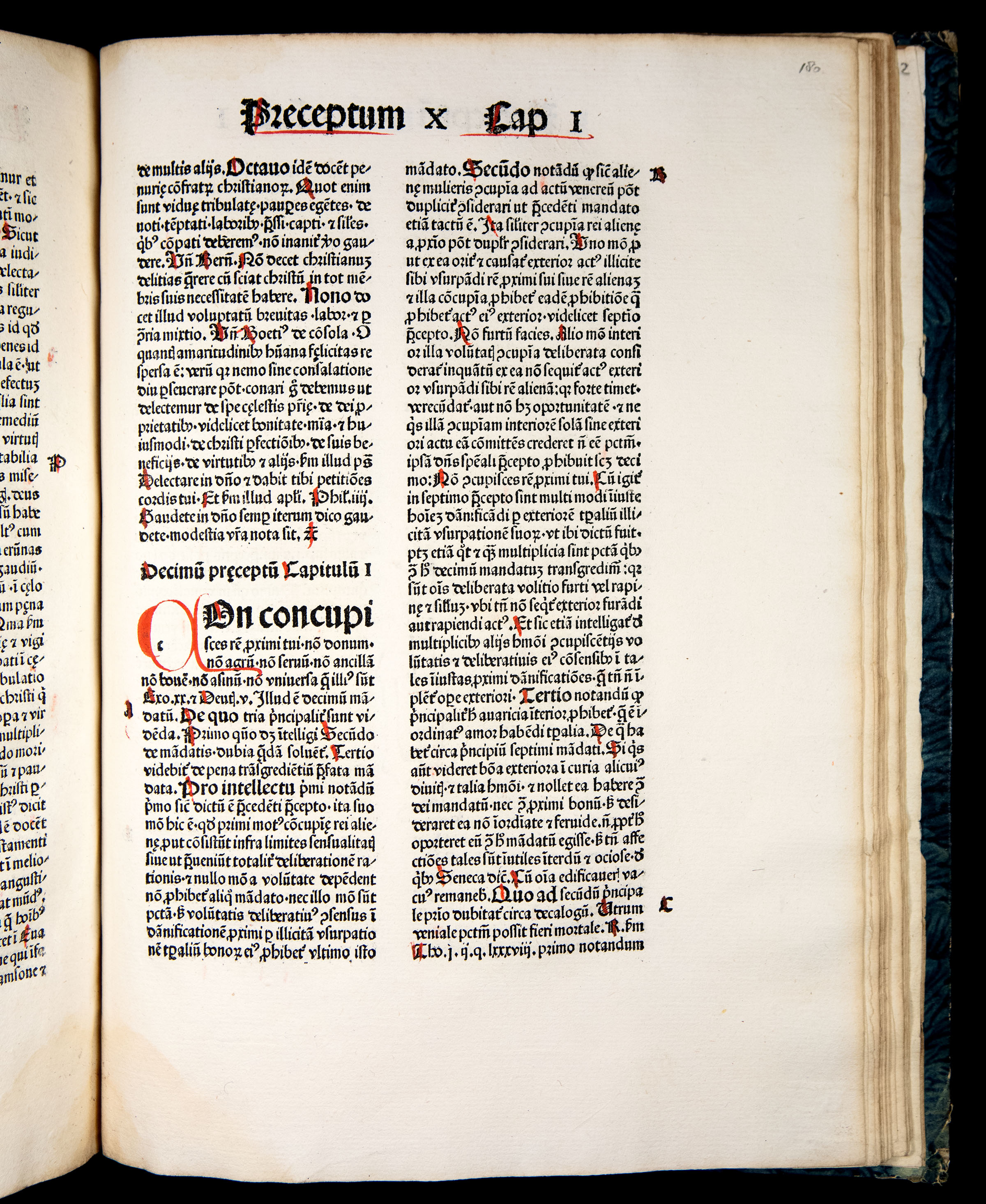

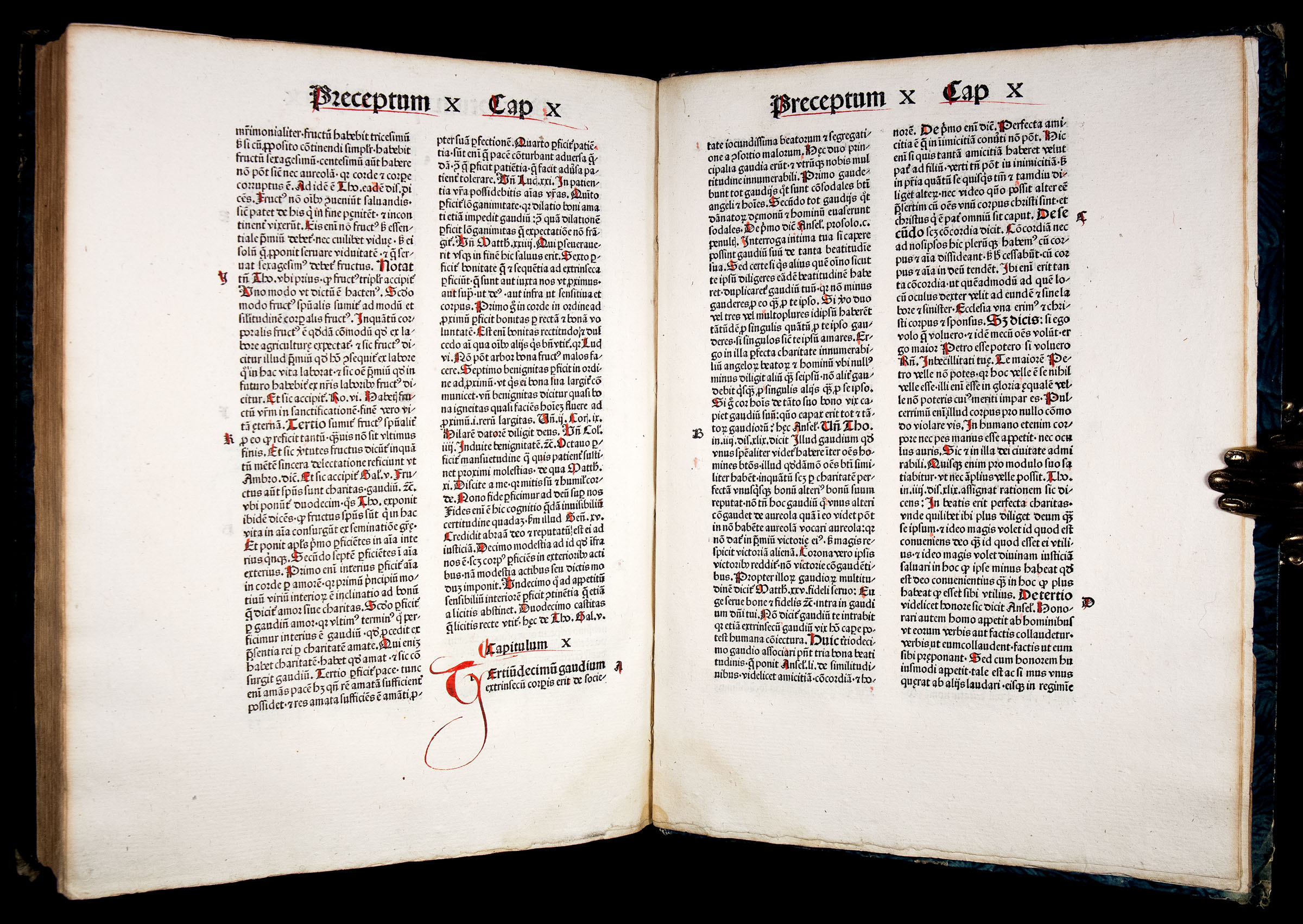

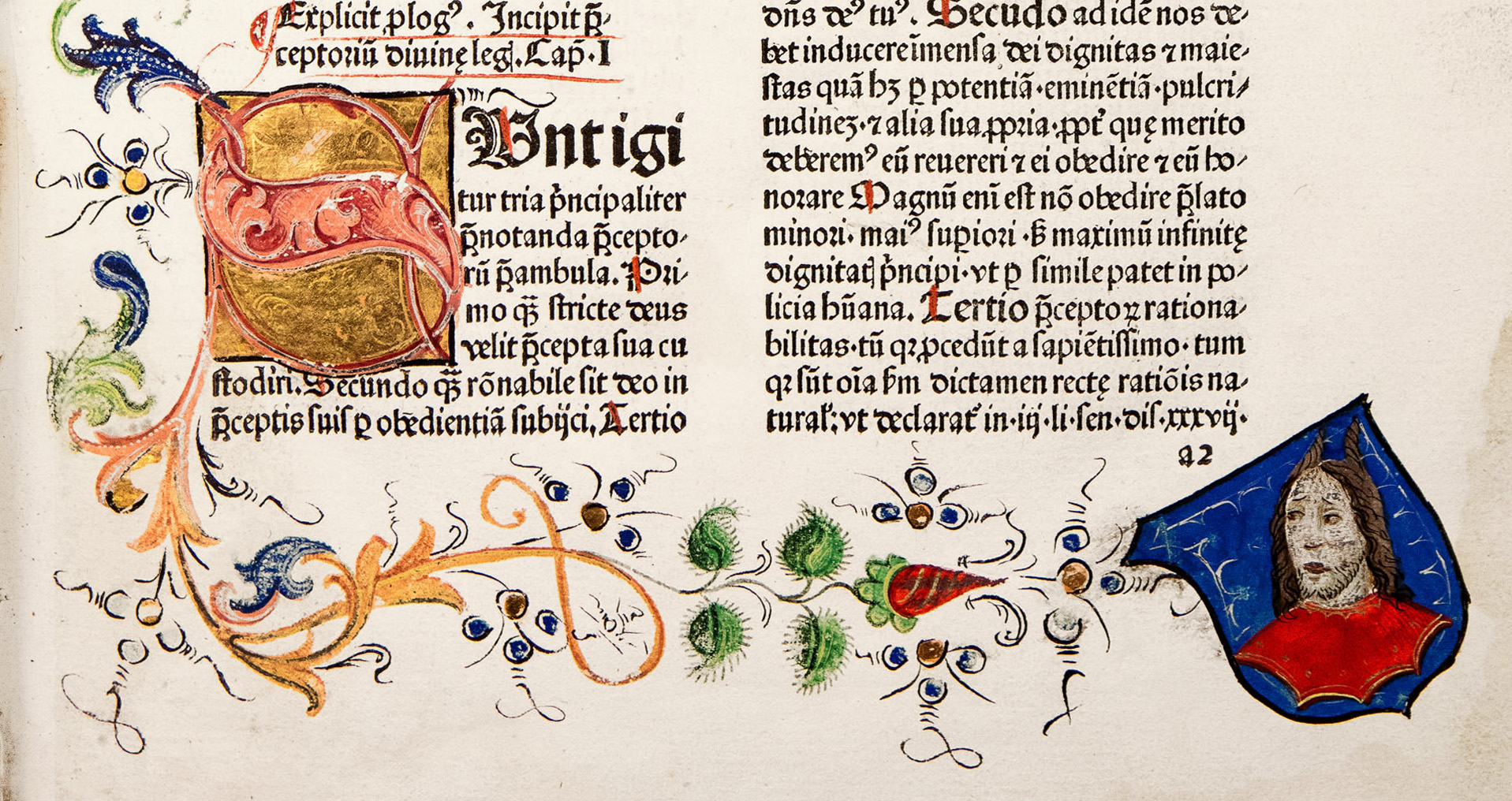

Text printed in gothic letter (Types 1: 185G, 3: 92aG, 5:106G); in double column, 44 lines per column, plus headline, initial spaces with printed guides. Attractively rubricated throughout in contemporary hand: with lombard initials supplied by hand in red and blue, intermittently, some with pen flourishes; paragraph marks and capital strokes in red; as well as red underlining to section headings and running headlines.

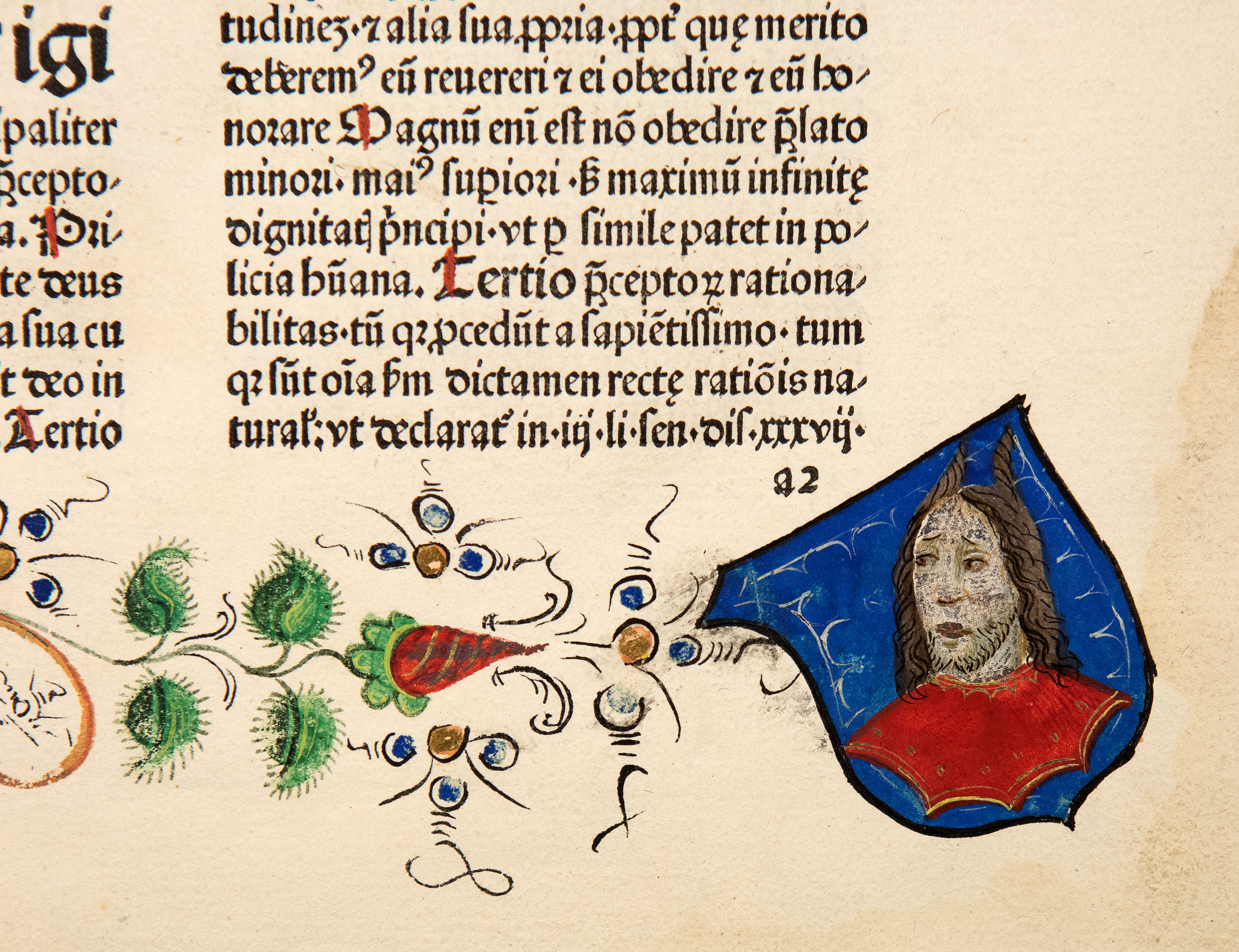

Opening page (a2r) beautifully illuminated with a fine 8-line painted initial ‘S’ (opening the text of Preceptum I) in ‘dusty pink’ with white tracery on the solid burnished gold background, with a marginal extension of winding vines, leafy sprays in green, blue and pink with gold bezants, forming a partial border within the bottom and lower inner margin, and incorporating (in the bottom right corner a well-executed and rather expressive portrait (presumably of the book’s original owner) on a blue escutcheon. Also on the same page is a 6-line painted lombard initial ‘D’ in blue with a penwork marginal extension.

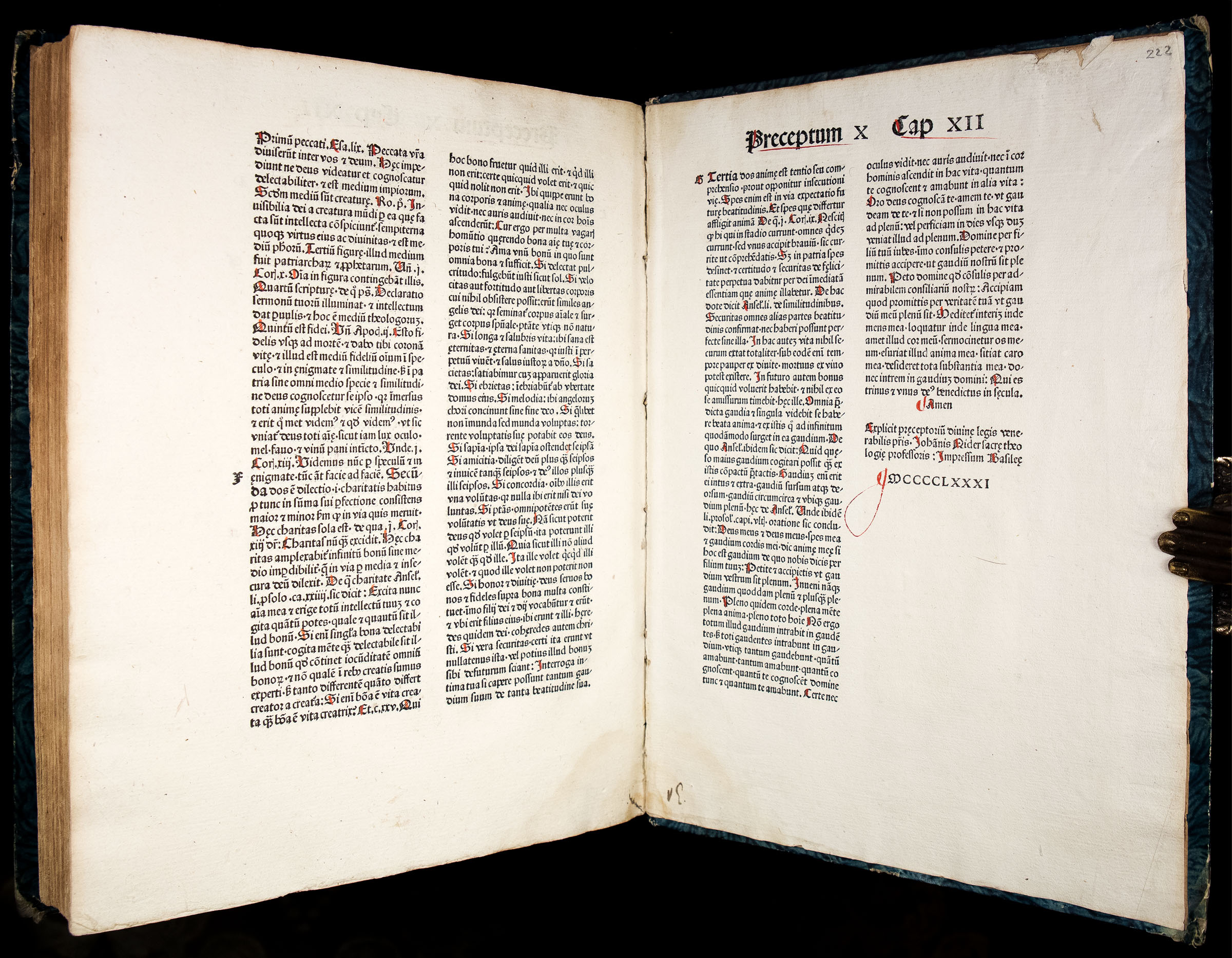

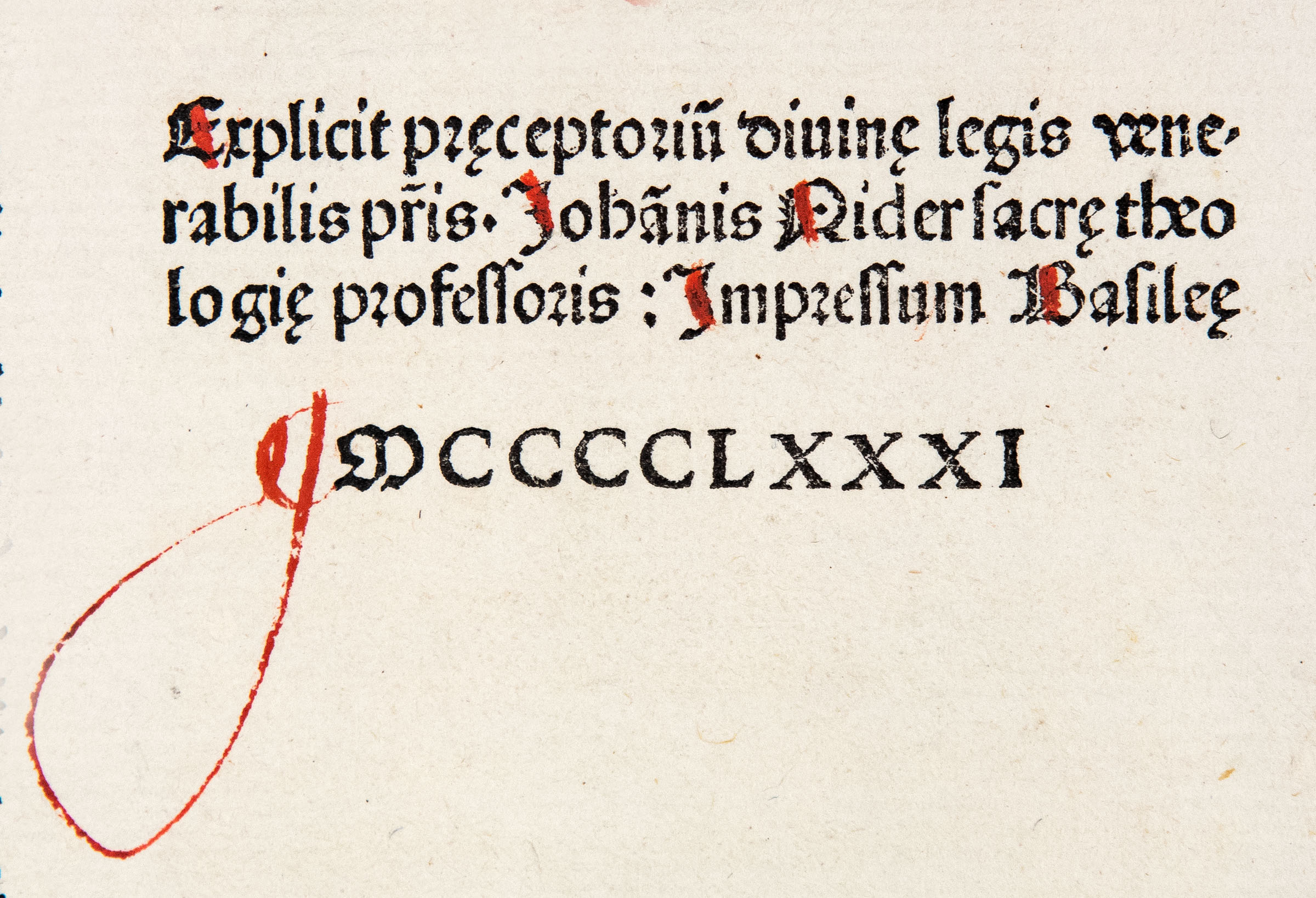

Colophon on recto of the final leaf [y10r] (verso blank).

Provenance:

A 17th-century (?) ownership inscription of a Dominican monastery at Dortmund (in Westphalia, Western Germany). A very well-executed portrait on a blue escutcheon (incorporated into the illuminated border on the opening page of text) presumably depicts the 1st owner of the book.

Condition:

Very Good antiquarian condition. Complete, except for the index (Tabula). Binding rubbed, with some wear to edges. Internally with light water-staining, mainly marginal; slightly more noticeable in the first quarter of the text-block (quires a-h), then diminishing and entirely confined to the inner corner of the bottom margin. A very attractive, wide-margined, genuine example of this finely printed, rare incunable edition, attractively rubricated throughout and with superbly illuminated opening page.